When All Hell Broke Loose

In the second of a two-part interview, veteran journalists John Egerton and John Seigenthaler talk about the time Wikipedia falsely implicated Seigenthaler in the death of John F. Kennedy

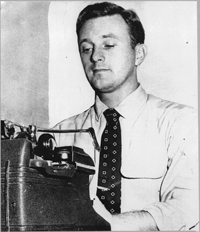

On October 15, veteran Nashville journalists John Egerton and John Seigenthaler sat down for a conversation in Seigenthaler’s office in the First Amendment Center on the campus of Vanderbilt University. Egerton, seventy-seven, a veteran freelancer and the author of many acclaimed books, came to Nashville in 1965 as a magazine staff writer and has been based there ever since. Seigenthaler, eighty-five, was born in Nashville, went to work as a reporter for The Tennessean in 1949, and retired forty-two years later as the paper’s editor and publisher. Egerton has called Seigenthaler “the foremost journalist in Tennessee history.” In addition to his contributions at The Tennessean, Siegenthaler also served as the first editorial director of USA Today, as chairman of both the John F. Kennedy “Profiles in Courage” Awards and the Robert F. Kennedy National Book Awards, and as founder of the First Amendment Center, which now bears his name. For more than forty years, he has hosted Nashville Public Television’s A Word on Words, a weekly interview program featuring prominent novelists, journalists, and historians from around the country.

Chapter 16 has published an abridged version of the Egerton-Seigenthaler conversation in two segments. The first, which appears here, focuses on books, newspapers, and the printed word. The second, which appears below, concerns a Wikipedia entry on Seigenthaler that erroneously implicated him in the murders of both John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy.

John Egerton: You were just a kid, twenty-two years old, when you started to work at The Tennessean.

John Seigenthaler: Right.

John Seigenthaler: Right.

Egerton: And thirty-five years later, after all these things have happened to you—everything we’ve talked about, plus the gazillion things we haven’t talked about, dramatic things we haven’t talked about: the Kennedys, the Sit-Ins, the Freedom Rides, all of that—we come to 1982. You’ve been editor of The Tennessean for twenty years, and now you become editor and publisher, and at the same time you also become the editorial director of the new USA Today.

Seigenthaler: Right.

Egerton: And then in another ten years or so, you retire from both those jobs. And that was twenty years ago.

Seigenthaler: Yep. Twenty-one years now.

Egerton: All kinds of things have happened, accolades that have come your way. The First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt, where we’re sitting right now, was created and you were made director right at the time you left USA Today. And the Chair of Excellence at Middle Tennessee State University was named for you; it became the John Seigenthaler Chair in First Amendment Studies. The First Amendment Center has now been named the Seigenthaler Center. In the eyes of a lot of people, you’ve become sort of the national guardian of the First Amendment. It’s synonymous with you. You’ve been a newspaper editor; you’ve written books; you’ve edited books; you’ve been a public person. Freedom of the press and of speech and all of those First Amendment rights have been right at the heart of your career. And yet, even since you retired, weird stuff has kept on happening to you.

Seigenthaler, laughing: It has.

Egerton: In 2005, Wikipedia posted a false bio—an unvetted biography—of John Seigenthaler, saying he was implicated in the assassinations of both John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy, saying that “he possibly has communist connections.”

Seigenthaler: Defected to the Soviet Union.

Egerton: Defected to the Soviet Union and came back. This was up on the web, what we now call the web, which didn’t even exist when you retired from The Tennessean and USA Today.

Seigenthaler: Right.

Egerton: And this is what you said when you found out about that: you said, “This is character assassination by Internet. This is putting truth a risk. There is no transparency, there is no accountability, and it could lead to government regulation of the Internet.” I want you to talk for just a few minutes about what exactly you see now, having been a newspaper guy all your life, having been somebody who holds this stuff in your hands. Proof is what you can pick up and hold. And now we don’t know what copyright is. We don’t know what proof means any more. Things can happen by Twitter, by the various ways on the Internet, and nobody’s in control of truth—whatever the hell truth is. Do you wonder what the Founding Fathers would have put into the First Amendment if we’d had an Internet then? How do you interpret all this?

Seigenthaler: You know, the whole question that you just asked finally comes down to accountability. I was sued, as editor of The Tennessean, somewhere close to twenty times. Only one of them ever went to a jury. Most of them were dismissed, either summary judgment or outright dismissal, by the judge. In most cases there was no substance to the charge, and that’s why we were acquitted. But you know, throughout my early years, a libel suit was always a possibility. And for all of us in those days, you’d stop and think before you published anything, because you didn’t want to get sued. I would guess that more than a hundred times during the ten years I was a reporter, I had to call Cecil Sims or Jack Norman….

Egerton: Lawyers….

Seigenthaler: …To get clearance on a story. So while you’re writing, you’re not thinking about it, but once you realize the possibility [of inspiring a lawsuit], then there’s a restraint. Now with Wikipedia, I immediately started getting calls from people saying, “Sue. Sue. Sue.”

I’m not going to sue somebody for saying something about me, even as scurrilous, as outrageous as it was. The truth of the matter is that I couldn’t sue Wikipedia. There is something called Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act that says you may not sue an information-service provider. So Google, Wikipedia, AOL—run down the list—if you’re an information-service provider, you’re immune to a lawsuit. As long as you publish somebody else’s work, or post somebody else’s work, and don’t alter it, you’re immune from lawsuits.

Egerton: As differentiated from the liability of a newspaper, a magazine.

Egerton: As differentiated from the liability of a newspaper, a magazine.

Seigenthaler: Absolutely, as differentiated. For example, if what they said about me had appeared in a letter to the editor, I would have had grounds to sue whatever newspaper published it, as well as the author. But under Section 230, the only thing you can do is file a John or a Jane Doe lawsuit. Get the IP number, the Internet Provider number, and find out what information-service provider dealt with the customer and posted it. And then if you sue John or Jane Doe, and go to court for an order, the court will order the information-service provider to tell you who it is. Then you may sue the individual who wrote it. But you know, if you have created something called the First Amendment Center, and if you’ve been sued, the last thing that’s going to cross your mind is to sue somebody for saying something about you.

My first thought is, “Nobody’s going to believe it. It’s funny.” And I chuckled until I got a call from my son, who says, “Look, you’re not the only John Seigenthaler. I’m John Seigenthaler, and you’ve got a grandson, Jack, who’s the third John Seigenthaler. Get that stuff off Wikipedia.”

And at that point I called Jimmy Wales [the co-founder of Wikipedia], and he took [the bio down], but within three days, it’s up there again. Somebody else puts it up again, and somebody else puts it up again, and they put it up again. Finally I wrote a piece in USA Today. Hadn’t written anything for USA Today from the time I retired, but I wrote a piece and said, “Wikipedia is an unreliable resource. It has great information on it, but it’s unreliable as a research arm and as a credible resource.”

And I will tell you, all hell broke loose. The worst was [the claim] that I had raped Jacqueline Kennedy. That was there on Wikipedia.

I got flooded with calls and emails and letters from people who said, “The same thing happened to me. I was glad to read your piece in USA Today. I had exactly the same experience.” And some really horrendous things have happened to people. You’re talking about a world that’s anonymous. I think Congress thought about it and decided, “This is going to be a new world of information, and, particularly given the potential for anonymity, you’re never going to keep up with it. And you’ll flood the courts. And so we’re going to write Section 230.”

And the question in my mind is, do I want to go back into Congress and say, “Hey, look what happened to me. Look what happened to all these other people” [and try to get Section 230 repealed]. But I decided Congress loves to regulate and loves the idea of regulating the media. And there are a lot of [congressmen] just itching to do it because if you go to Wikipedia and get their biographies , the same thing is happening to them. And most of them have somebody on their staff trying to keep their Wikipedia biographies straight.

I just finally concluded that the time had come for people to wake up to the fact that this stuff is there, and you’re going to have to search for what’s credible, and what’s believable, and you’re going to have to treat the rest of it as if it’s trivia.

You ask me what’s going to happen. What’s going to have to happen is that the old values that governed journalism—the old values of staying as close to accuracy, searching for the truth, as if there were still a libel law there—have got to be maintained in the new electronic world. You’ve got to maintain the old standards, the old standards of journalism that made newspapers credible.

Egerton: But is it fair for those standards to be applied to newspapers and magazines, and not be applied to the new media?

Egerton: But is it fair for those standards to be applied to newspapers and magazines, and not be applied to the new media?

Seigenthaler: It is unfair. It is unfair, and I accept that. But the option is to go into Congress and say, “Make them [behave] like us” —and do you think for a minute they’ll stop? You know, I love to quote Jefferson and Madison and Ben Franklin, but it was Alexander Hamilton who said, when they were talking about freedom of the press at the Constitutional Convention, “Whatever fine declarations may be inserted in any constitution respecting [its security], must altogether depend on public opinion, and on the general spirit of the people and of the government.”

He’s telling you, “Yeah, they may give it to you, but you just better remember that somebody can take it away from you.” And that quote has lived with me since I first heard it. I mean, we can lose this thing.

One of the reasons I started this First Amendment Center is because I thought if we can elevate the discussion, the debate and dialogue, in the face of this exploding new [technology]—then we’ll be all right, and we can [protect and preserve] the First Amendment.

Egerton: But the threat of a lawsuit, you’re suggesting, was important.

Seigenthaler: Yeah. Very important. I know nobody likes to admit it, but it was a restraint. It made you think twice. And now, in the same way that we’re talking about libel suits and copyrights and other First Amendment issues, a whole wave of people is ignoring intellectual property rights by stealing music from the Internet.

What we really need—and ultimately I think it will evolve—is one or more sources of news that are deemed as credible and reliable as, say, the Associated Press. But first we’re going to have to go through this damned tragic period in which an awful lot of people, including me, get their names blackened. I could have gone through the process of filing a John Doe lawsuit to find out who [had libeled me]. I ultimately found out who did it anyway.

Egerton: But you couldn’t do anything about it, essentially.

Seigenthaler: I couldn’t do anything about it, and I didn’t—you know, he was contrite about it.

Egerton: Who’s going to watch the henhouse, when the newspapers are gone? Just the foxes?

Seigenthaler: I used to say, when I was still in [newspapering], “You don’t have to believe what I wrote, or what I published. I want you to believe it, and I’ve gone to a lot of effort with a lot of people who are professionals, and we all hope you believe it. But we can’t make you believe it.” And that was what Hamilton was talking about, what he was warning about: “Yeah, we can give it to you, but we can take it away from you, too.” And unless people understand that it can be taken away…. I think if Section 230 were not there, we’d have a healthier world-communications [environment]. But….

Egerton: You don’t think it’s going to change?

Seigenthaler: I don’t think it’s going to change, and I think if you go in there and try to get Congress to change it, Congress will do what it inevitably does and go way beyond any realm of reasonable or rational regulation. I think you need regulation in most of corporate America, but in the area of free expression, the danger of suppressing independent free thought is much greater than in any other area of corporate America.

Egerton: But here’s the irony. You can write a book and publish it at an established publishing house in New York, and there will be a clause in your contract that says, “If you get sued, we will come to your defense.”

Seigenthaler: Yep.

Egerton: “We will fight together. We will share the cost, we will do the defense.” You know what happens if you get a book published in a new-media format, like books on demand, or so-called instant books?

Egerton: “We will fight together. We will share the cost, we will do the defense.” You know what happens if you get a book published in a new-media format, like books on demand, or so-called instant books?

Seigenthaler: You’re vulnerable.

Egerton: If you ask the editor, “Where in my contract does it say that you will defend me if I’m sued for anything I say in that book?”

They will say, “We are not concerned with the content of this book. Our job is to print it and put it out there, and the liability is totally your own.”

Seigenthaler: And that’s exactly what the e-world is. And frankly, there are times when I wish the [legal] restraint were still there. I just worry a great deal that once you start regulating speech, Congress will go beyond the pale. And the result will be a wave of litigation for the repression of speech. As painful as this period has been—and is, and was to me personally—it’s not easy, but I finally come down against trying to repeal 230.

I honestly believe you could do it because enough congressmen and senators and governors and presidents have been burned online. Jimmy Wales, he’s got a faceless cadre of volunteer monitors that ultimately decides what goes up on Wikipedia and what comes down. Who the hell are they? What are their qualifications? That’s just crazy. I’ve had a face-to-face confrontation with Wales. I gave him hell for an hour, he gave me hell for an hour, and then Al Gore moderated an exchange between us. I can’t understand the guy. I cannot get my head around where Jimmy Wales is coming from in this outrageous insistence that anybody can put anything up on the Wikipedia website, anonymously, and not be responsible for it.

Wales is claiming, “I’ve got these administrators who will catch any error.” Well, there was an error. There were a number of errors, but there was one basic error in my first biography: it said in the early 1960s I was an assistant to Robert Kennedy. Misspelled the word “early.” And within five minutes they caught it, and they corrected the word “early”—and left me a suspected assassin and defector.

Egerton: That says a lot.

Seigenthaler: It says a lot. They could do it, get it right, if they wanted to do it. And if the [threat of libel suits] was there, they would do it. Now, you know, it would be costly—Wikipedia lives only by donations—but it wouldn’t take long for them to get it right.

Here’s the way I look at it. I think we’re going through a phase. And it might take a decade, or two decades, to shake down through this period. And the odds are very strong that we’re not going to get through it without some regulation because the abuse is not going to go away. But more and more people are going to try to cleave to the old values, and that will help some. And then there are going to be abuses that are more and more flagrant, and ultimately, ultimately, Congress will come to a time [when they decide they have to regulate the new media], and a balance will be found.

I prefer to wait until that time and fight to keep as much freedom as we possibly can, because once they get their hands on regulating free expression, the dangers of repression setting in are just too real.

[To read the first part of this conversation, please click here.]

On October 30 at 7 p.m., John Seigenthaler will speak on “First Amendment Challenges Posed by New Media Technology” at the Massey Performing Arts Center on Belmont University campus in Nashville. The event is free and open to the public. Click here for ticket details. On November 8 at 11:30 a.m., Seigenthaler will receive the Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee’s 2012 Joe Kraft Humanitarian Award. Tickets to that event are $75. Click here for details.