When Life Was Simpler

Women reflect on their mountain upbringing

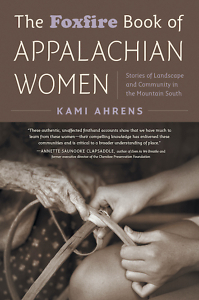

The Foxfire series, as editor Kami Ahrens explains in the introduction to The Foxfire Book of Appalachian Women, began when “a group of rowdy high school students and their English teacher in Rabun Gap, Georgia, decided to create a literary magazine in 1966.” The first Foxfire Magazine, published in 1967, featured not just poetry and prose from the community, but interviews with locals as well. Over the years, such interviews have played a central role in the Foxfire project, but as Ahrens states, “While stories of women, bonded by common threads of place and culture, are scattered throughout the Foxfire publications, we’ve just now identified the need to craft a book dedicated to the Appalachian women whose stories were carefully collected by our Foxfire students.”

The Foxfire Book of Appalachian Women contains compiled interviews from 21 notable women, many of whom were born in the late 19th or early 20th century. Each woman’s section of the book weaves multiple interviews done over time to create a fluid, comprehensive narrative. Every interview subject is a unique individual, and the stories are informative and nuanced, but the women share many similar opinions: for example, that children used to be happier, people have lost touch with religion, and simple, rural living is more comfortable and restful than city life. As Margaret Norton, a Georgia woman first interviewed in 1967, explains, “Some people say the only way out now is for people to go back to the way they’s livin’ fifty years ago. Wonder how the young people’d feel about that?” Many women, such as Carrie McDonnell Stewart, who was born in North Carolina in 1878, describe a childhood filled with chores and responsibility. Stewart expresses the shared belief that parents are to blame because of their lack of attention and discipline for the state of children today. As she states:

In one way, I think the parents are to blame for the children getting in so much trouble and all now. They don’t give them something to keep them busy and interested in. They just turn the children loose and don’t know where they are half the time. And I just think if a young person doesn’t get an education or get into something worthwhile, then it’s because he or she’s just too lazy to try. Now when children get sixteen, seventeen years old, they think, “I can sort of do as I please now.” And then they step out, and they step in the wrong place. They don’t think anything about it ‘til it’s too late.

Many of the women share their thoughts and opinions on subjects beyond home and family life. For example, Mary Carpenter from Scaly Mountain, North Carolina, explains why she believes the moon landing to be a hoax. “No,” Carpenter says, the astronauts “didn’t go to the moon; that’s a bunch of fooie!” Carpenter believes that the astronauts simply climbed into the shuttle and then through a trapdoor back out of the shuttle. Then the shuttle “just goes up and goes on a mountain or a desert somewhere and they put on them old clowny suits and dig and peck.”

Many of the women share their thoughts and opinions on subjects beyond home and family life. For example, Mary Carpenter from Scaly Mountain, North Carolina, explains why she believes the moon landing to be a hoax. “No,” Carpenter says, the astronauts “didn’t go to the moon; that’s a bunch of fooie!” Carpenter believes that the astronauts simply climbed into the shuttle and then through a trapdoor back out of the shuttle. Then the shuttle “just goes up and goes on a mountain or a desert somewhere and they put on them old clowny suits and dig and peck.”

The book details a shared disbelief and awe regarding industrial progress. Anna Tutt, a Georgia woman interviewed in 1976, describes the teacher at her school telling students that the men outside digging ditches will soon be replaced by a machine with a single operator that will dig faster than the men could. As Tutt recounts, “We said, ‘Oh, he doesn’t know what he’s talking about.’ We couldn’t see it back then, but it’s here now. Everything’s push-button.” Many women, despite the invention of modern household innovations, such as indoor plumbing and electric stoves, prefer the traditional methods of hand-churning butter and cooking on a woodstove.

Through it all, the women’s voices share tales again and again of a tight-knit community that worked organically as a collectivist society rather than the individualist society of contemporary America. When someone in the community was sick, neighbors would take that person in, no questions asked. When a family suffered a bad harvest and did not have enough food stockpiled to make it through the winter, the community made sure they were fed. The givers didn’t ask for anything in return, but it was an unspoken truth that those in need one year would pay it forward next time someone else required help.

In the end, the women agree the mountains are the place to be. Georgia native Addie Parker Norton explains, “I think we’re the luckiest people in the world right here. I’ve been all across the United States . . . and I’ve not found anywhere yet that I love more than these mountains.” It’s only fitting to end with Mary Carpenter’s succinct statement: “Oh, I like it back in the mountains.”

Abby N. Lewis is an adjunct English instructor at ETSU. She is the author of the poetry collection Reticent, the chapbook This Fluid Journey, and the newly released chapbook Palm Up, Fingers Curled from Plan B Press.