When Outlaws Ruled the West End

Michael Streissguth explores the rise of country music’s outlaw movement

I didn’t listen to Kris Kristofferson until I got to college, but I was three years old when I broke the needle on my parents’ record player after wearing out a seven-inch of Johnny Cash’s “Daddy Sang Bass.” The next year, one night in 1979, I remember sitting cross-legged on an earth-toned shag carpet in the living room and watching blow-dried hillbillies drive a burnt-orange Dodge across our TV while banjos played in the background and a “balladeer” explained the characters’ predicament with the dastardly Roscoe and Boss Hog. That balladeer was Waylon Jennings, and that night was the first time I heard him sing. Pretty soon, I was obsessed with his duet with Willie Nelson, “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Cowboys.” I even developed a crush on two kindergarten classmates who sang that song during show-and-tell every week.

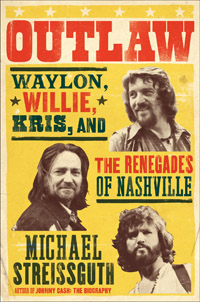

In the late 70s, Waylon, Willie, and the music of country-music’s outlaws was everywhere, and it served as the soundtrack of my childhood. But before outlaw was ubiquitous, the music and the artists who made it were earning the moniker by shaking up the very heart of conservative Nashville. In his new book, Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville, Michael Streissguth provides an in-depth look at the rise of this renegade country-music movement, how it changed Nashville, and the formidable talents who led the way.

In the late 70s, Waylon, Willie, and the music of country-music’s outlaws was everywhere, and it served as the soundtrack of my childhood. But before outlaw was ubiquitous, the music and the artists who made it were earning the moniker by shaking up the very heart of conservative Nashville. In his new book, Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville, Michael Streissguth provides an in-depth look at the rise of this renegade country-music movement, how it changed Nashville, and the formidable talents who led the way.

Part biography of Kristofferson, Jennings, and Nelson and part exploration of the changing music scene in Nashville of the late 60s, Outlaw looks behind the curtain at this major turning point in country-music history. These artists—along with Johnny Cash, Kinky Friedman, Shel Silverstein, Rodney Crowell, Billy Joe Shaver, and others—picked up on the unrest of the late 60s and early 70s and began exploring it through their music. Challenging the industry’s hierarchy and unwritten rules, they worked to establish a new genre of country music, one that would ultimately change the recording industry. Prior to his appearance at Parnassus Books in Nashville, Michael Streissguth answered questions about the book from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: Social change was afoot in Music City during the civil-rights era: sit-ins, anti-war activism, and an emerging counterculture. How did country radio react when these socio-political shifts were addressed by the songs coming from Outlaw artists? Was there a backlash similar to what happened with the Dixie Chicks a decade ago?

Streissguth: Country radio has often resisted changes in the recording industry, specifically new sounds and themes presented by pioneer artists. The music that reflected social and political change in the late 1960s and early 1970s first found a home in underground formats or progressive formats. Such themes certainly never dominated country-music radio formats, but they did slowly emerge in the mainstream.

Chapter 16: The artists you profile in Outlaw are notable for their pursuit of artistic freedom and independence at a time when it was rarely granted by Music Row’s powers-that-be. What do you think was the most important turning point in giving these artists more control over their music?

Chapter 16: The artists you profile in Outlaw are notable for their pursuit of artistic freedom and independence at a time when it was rarely granted by Music Row’s powers-that-be. What do you think was the most important turning point in giving these artists more control over their music?

Streissguth: Johnny Cash had enjoyed independence in the studio going back to the late 1950s, but he was an exception. When Waylon Jennings and his manager Neil Reshen negotiated almost complete artistic freedom for Waylon in the early 1970s, the floodgates opened. By and large, record labels ceded the creation of the music to the artists and concentrated on signing artists and marketing them.

Chapter 16: You write about the role outlaw music played in mainstreaming Southern popular culture during the 1970s. Did it also fuel Southern stereotypes?

Streissguth: I offer a broad definition of outlaw in the book. Yes, it includes a Jesse James archetype, but it also encompasses those who pursued their own course in the music business, ignoring formula, no matter how they dressed or comported themselves. Some who have adopted the Jesse James archetype in the years since Waylon and Willie cooled have often exhibited jingoistic attitudes that some might associate with the South. To the extent that there was outlaw rhetoric in the 1970s, jingoism was largely absent from it.

Chapter 16: Was there a particular death knell for the outlaw movement?

Streissguth: I think it rang in 1977 when Waylon was arrested for cocaine possession. The excesses of the era had begun to overshadow the music and the message of independence. Besides, a new generation of artists (new traditionalists and blow-dried heartthrobs) were waiting in the wings to take the stage.

Chapter 16: For more than a decade, Americana stations and Internet radio have provided a specific home, albeit a small one, to artists who draw from the outlaw well. With radio and the Internet so effective at segregating genres, how likely are we to see another such sea change in popular country music?

Streissguth: Just when country music is turning beige and indistinguishable from the landscape around it, creative forces always punch through with new and invigorating attitudes and sounds. So country music always seems capable of saving itself from itself. Redefinition is always around the corner.

Chapter 16: Today, outlaw has become a genre archetype, defined as much by the industry as it is the artist. Do you think the label means anything these days, or is the term more an exercise in marketing?

Streissguth: Since the 1970s, the term has been an exercise in marketing. However, in the 1970s it was also an exercise in the pioneering of new sounds and the pursuit of one’s own creative vision. We don’t call them “outlaws” today, those who shirk formula. But they are outlaws nonetheless. Trust me, they’re outlaws.

Michael Streissguth will discuss Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville at Parnassus Books in Nashville on June 20 at 6:30 p.m.