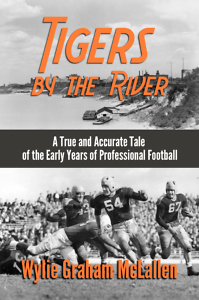

When Piggly-Wiggly Met Pigskin

Wylie McLallen recovers the forgotten history of football in Memphis

When you hear “Memphis Tigers,” you naturally associate it with the teams at the University of Memphis (or Memphis State University, if you are of a certain age and trying to cork the sands of time). But Zach Curlin, athletic director at the school in the 1930s, adopted the mascot from a short-lived but notable professional football squad in Memphis. In Tigers By the River, Wylie McLallen recounts the history of that team, illustrating both its on-field exploits and the principals’ backstories.

McLallen grew up in Memphis and received his degree in history and English from the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. While maintaining a career as a programmer analyst and then as a small business owner, he has written both history and fiction. He now lives in Vancouver, British Columbia. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

McLallen grew up in Memphis and received his degree in history and English from the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. While maintaining a career as a programmer analyst and then as a small business owner, he has written both history and fiction. He now lives in Vancouver, British Columbia. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: Two of the key early figures in this story are sportswriter Early Maxwell and Piggly-Wiggly mogul Clarence Saunders. How did these men help bring professional football to Memphis?

Wylie McLallen: In the fall of 1927, Early Maxwell, a twenty-two-year-old sportswriter for The Commercial Appeal, organized one of the first professional football teams in the South: the New Brys Hurricane, which was sponsored by a local department store named New Brys. The 1920s were the first great era of professional sports in America; major league baseball was at the forefront, but tennis, boxing, and auto racing were also prominent. Pro football was a fledging sport, but it was exciting and rapidly growing in the big manufacturing cities of the Midwest and Northeast. Early Maxwell, an athletic young man with an entrepreneurial spirit, saw a definite opportunity for his city in this burgeoning market of professional sports.

Then in 1928 one of the wealthiest men in the South, Clarence Saunders, the founder of Piggly-Wiggly grocery stores, became interested and bought the team because his son wanted to play pro football. Saunders quickly became very enthusiastic about pro football. He hired Early Maxwell as an advisor, renamed his team The Sole Owner Tigers (after his current chain of grocery stores), secured contracts with some of the best players in the country, and lured the best professional teams to Memphis to play before packed crowds in the only available stadium, Hodges Field, whose stands held ten thousand people.

Chapter 16: In 1929 the Memphis Tigers proclaimed themselves the national champions of professional football. How did that happen? Was their claim justified?

McLallen: By the end of the season, the 1929 Memphis Tigers were the best football team in America. What Clarence Saunders achieved was quite astonishing. He was able to do this by listening to Early Maxwell, who knew the game well, and by using his skill and vast resources to sign great players and schedule the best teams.

Saunders also provided dynamic leadership both on and off the field. The Tigers demolished the best independent pro teams in the country with great defense and an explosive offensive, even beating a good team from St. Louis by a score of 64-0, and then rolling over NFL teams like the Chicago Bears and the Green Bay Packers. In fact, when the Packers came to Memphis in December they were the undefeated NFL champions and considered one of the best football teams up to that time. But the Tigers, who by the end of the season had three players on their roster later to be among the first players inducted into the NFL Hall of Fame, defeated them 20-7 in a game that almost became a rout.

Chapter 16: It seemed like the Great Depression would cripple pro football in Memphis. How did the team survive these lean years?

Chapter 16: It seemed like the Great Depression would cripple pro football in Memphis. How did the team survive these lean years?

McLallen: Clarence Saunders went broke soon after the stock market crashed in 1929, but, even without his wealthy backing, the Memphis Tigers continued playing pro football for another six years. They played very well, too, which is how they were able to keep the public’s attention. In 1930 a group of businessmen organized a corporation to support the team and the roster had even better players than the year before, but they lacked leadership and did not win as many games.

In 1931, under the helm of Early Maxwell, they were probably the best independent pro team in the nation. They remained very good for the following three seasons and could still draw a good crowd when they played against great NFL teams. But the times were very hard. It was a segregated society and the Great Depression deepened, with unemployment reaching almost thirty percent, and the Tigers did not have enough public support to survive beyond the 1935 season.

Chapter 16: What was the status of professional football in these years? How did it measure against the college game?

McLallen: In the late twenties, the NFL was still only a fledging league, drawing maybe a few thousand people to games on Sundays. Pro football as a whole was loosely organized, with a lingering unsavory reputation. Most teams lost money and quickly folded. In contrast, college football was a very admired sport as tens of thousands of fans filled the big stadiums at universities all across the country throughout the fall on Saturday afternoons; only major league baseball was more popular.

Yet the popularity of pro football was slowly growing as fans remained interested in what happened to great college players after they finished their college careers. When the most famous player of the age, Red Grange of Illinois, was signed by George Halas to play for the Chicago Bears, huge numbers of people packed big stadiums to watch his first games as a professional, even though it was December and the official season was over. This was a turning point for the professional game, and its popularity began to increase thereafter, but it would not match that of the college game until the late fifties and early sixties.

Chapter 16: What might the story of these Memphis Tigers reveal, more broadly, about the place of professional football in the South?

McLallen: It shows that despite a magnificent effort, the South was not yet ready for a major professional football team. In fact, it was not until 1960, when the Dallas Cowboys joined the NFL, that the South would have a major franchise. I believe this was largely because of the Depression, but there may have been other factors, too, such as population and economics. The cities in the North had much larger populations than Southern cities and had more manufacturing and wealth. The North also had a more seasoned and organized labor force, with better paychecks than their Southern counterparts, who would buy tickets to watch professional football games. And, to be honest, the South was also more mired in segregation, with a larger population of African Americans who were poor and disenfranchised citizens.

Chapter 16: What is the legacy of this team? How does their tale fit into a larger narrative of Memphis sports history?

McLallen: What is most extraordinary about the Memphis Tigers is that, despite their excellent play on the field, their story was all but forgotten. When my father, who watched their games as a boy, first told me about them and how good they were, I hardly believed him. I wonder how many people even know that Zach Curlin, the athletic director at what was then West Tennessee State Teachers College, who had also been a referee at the Sole Owner Tigers’ games, named his college’s athletic teams in their honor. That school is now the University of Memphis and their teams are still known as the Tigers—which in itself is a very fine legacy for an excellent professional football team of a long-gone era.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.