When Things Picked Up

The world probably had room in it — even for me

“Well, as you might have guessed from my name, I’m John Steinbeck’s son,” the shaggy, dark-haired kid told me. I was newly unpacked on my first day at an undistinguished New England prep school, and he had wandered into the room and introduced himself as John-Steinbeck-the-fourth.

He sat down at the tiny wooden table crammed between the wall and the bed, took a Barlow pocket knife out of his pants, opened it, and started carving a groove into the first joint behind the tip of his forefinger. I winced. Blood began dripping on the varnished wood tabletop.

“Yeah, that John Steinbeck,” he continued. “Famous writer and all. I’m not here for long, I’ll take off from this shithole in a couple of days. I was in a lot of schools last year, and I didn’t stay long at any of them. I won’t be here long, either.”

Despite his odd behavior, I was glad for his company, any company. I had been lying on my narrow bed trying to hold off the growing sense of fear and abandonment that threatened to overwhelm me at any moment. I was alone and lonely, far from Nashville, the only place I had ever lived.

I came from an orderly home, two parents loving in their treatment of me, both of them known and highly regarded in the community. Despite my privileged adolescence, I was a scrawny, angst-ridden teenager who had been the shortest male in my high school class and, I was certain, the ugliest. My entire teenage social life, what there had been of it, had taken place within the confines of Nashville’s Jewish community. Jews in Nashville exemplified what white Nashvillians falsely maintained they offered to Black people: separate but equal. Jews were, in fact, granted equality with the Christian power structure, as long as they kept to themselves and did not do a lot of mixing with Christian white people.

Mixed marriages were discouraged in the strongest terms, as was any sort of socializing between the religions, particularly among the young, unwed, hormone-ridden youth. Nashville’s Jewish adults had their own country clubs, community centers, illegal gambling casinos, and nightlife, and the Jewish youth had their own fraternities, sororities, cliques, and social networks. I had little social life, Jewish or otherwise, and spent most weekends alone and miserable.

I was prone to acting out my anxious, unhappy, 16-year-old self through bad grades, disobedience, and insolence toward my elders, which got me in endless trouble at my all-white, segregated, suburban Nashville high school. My behavior was throwing a big damper on my prospects for higher education. Even as I acted out, my parents were unable to imagine that I was not college material. They found a preparatory boarding school that did not have strict genetic or prior behavior entrance requirements, dug deep into their pockets, and sent me north.

How, I was wondering, could homesickness affect someone who was so sick of home? On the first day in that Massachusetts prep school, I was missing my old life something fierce. All the things that had made up my day-to-day were gone in a stroke, and I could not imagine how they would ever be replaced. It seemed impossible that I could get through the years ahead. I was convinced that little good and lots of bad were in store for me, and that I deserved them, even if I couldn’t quite say why. Stretched out on that narrow bed, inside a brick building set down amidst the wooded hills of north-central Massachusetts, I was feeling like the smallest, most twisted human alive.

Then, John Steinbeck IV came into the room and began to go to work cutting his finger down toward bone, while he kept up a steady monologue, mostly bragging about his sins. I dug a recently unpacked white handkerchief out of a dresser drawer, still as clean and unused as when my mother had ironed, folded, and tucked it into my suitcase. I spread it on the tabletop beneath his finger. “Hey, you’re gonna do yourself some serious damage,” I tried to interrupt his monologue about the schools he’d been kicked out of, and the hell he’d raised. “And you’re making a mess of that table.”

He stopped talking and looked down, quit carving on himself, folded the Barlow blade, and put it back in his pocket. He picked up my handkerchief and wrapped it tightly around the deep cut. “Well, good luck,” he said in farewell, wandering out of my room and into the hallway, taking my handkerchief with him.

I never got it back. True to his word, John Steinbeck IV was gone to find trouble elsewhere after three days, but on that first day he had taught me the most important lesson I would carry away from prep school, and on to university two years later. He showed me that I was far from being the weirdest kid in the world, a world that was much larger and more bizarre than I had ever imagined in Nashville, a world that probably had room in it even for me, a world that might well take me a full and interesting lifetime to explore.

John Steinbeck IV would go on to work as a prize-winning reporter covering the war in Vietnam, do a lot of drugs, and become a Tibetan Buddhist, before dying way too young at the age of 44. I have arrived at a ripe-enough old age, approaching twice his, although I may not have done all that great a job of it. The particular life I have lived has had its ups and downs, full of moments when I have not done what I could have, or should have, but I began to feel better the minute Steinbeck walked out of that room, and I have yet to feel worse.

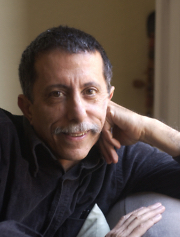

Copyright © 2023 by Richard Schweid. All rights reserved. Richard Schweid is a Nashville native and the author of more than a dozen books, including Octopus, Invisible Nation, and The Caring Class. He lives in Barcelona, Spain.