When to Hold on and When to Let Go

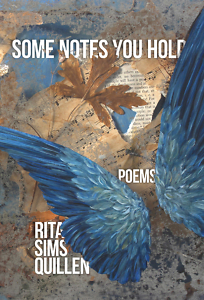

Rita Sims Quillen’s sixth poetry collection focuses on the restorative power of being present

Some books serve as fuel to replenish our spirits; others spark fire to mobilize our actions. While both types are needed to face the trials of this world, Rita Sims Quillen’s Some Notes You Hold is the former type. Through precise details and crafted metaphors with a focus on the Appalachian landscape and family memories, the poems in this collection remind us to pause, breathe, and see the beauty around us.

Quillen, who taught at Northeast State Community College in Blountville for 13 years, divides her captivating book into three sections. The first focuses on surviving deep grief and is centered around family, specifically her father. In the second section, Quillen focuses on ways to cope with grief, in part through gratitude. These poems, with titles such as “Why I Dance,” “Why I Sing,” and “Why I Play Music,” testify to the powers of self-care. The poems in the third section continue their insistence on finding the joy among the sorrow, chiefly through writing, music, prayer, and a deep communion with the natural world.

Quillen, who taught at Northeast State Community College in Blountville for 13 years, divides her captivating book into three sections. The first focuses on surviving deep grief and is centered around family, specifically her father. In the second section, Quillen focuses on ways to cope with grief, in part through gratitude. These poems, with titles such as “Why I Dance,” “Why I Sing,” and “Why I Play Music,” testify to the powers of self-care. The poems in the third section continue their insistence on finding the joy among the sorrow, chiefly through writing, music, prayer, and a deep communion with the natural world.

Embedded within each poem is a call to be present, as detailed with these lines from “Prayer of the Restless Son”: “May I pay attention today / to the call of birds / first warm breath of spring / sunlight glinting off a pretty girl’s long hair.” It’s clear that writing poetry is an act of attention for Quillen, a way to center the self and be present.

Radiating throughout the poems is Quillen’s deep love for music and her awareness that song requires us sometimes to hold a note and other times to let it go — a microcosm for coping with life. In “New Year’s Resolution,” she recalls a tree “where the crippled fox / sent me a poem across silent snow.” As she documents what she loves and what she has lost, Quillen’s poems form their own path for the reader, one that guides us, like that crippled fox, through the silent snow.

Rita Sims Quillen answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: One of the book’s finest achievements is its ability to convey a love for life despite its hardships. Is this something that you intended from the outset, or did the act of writing the poems lead to the transformation?

Quillen: No, not really a conscious thing. The book began with the poems about my dad as I tried to write my way out of grief. Over time, as those poems seemed to stop coming, I began to write the series of poems about music: why I love it so, why it makes me so happy. I realized then that I was trying to write my way to a better place and to become reconciled to this new world I was living in, where loss and grief would now become a fixture of the landscape.

Chapter 16: One delight in the book is the attention paid to nature and how the landscape can help center us. Gardening, too, has an almost redemptive power. These lines from “Garden Rite” describe the father’s dedication:

He plunged little crosses in the ground

where tomatoes, smeared with stigmata

of juicy joy, would shine over the garden.

Not a thing wrong with the bread and the wine

but a country boy had to have beans.

Are you an avid gardener? How does nature soothe in ways that are different from writing?

Quillen: When I was a kid and Dad would make us help him work in his garden, I wasn’t a fan! But as I got older, I enjoyed having a vegetable garden and fruit trees, putting up all that bounty in the freezer or in jars to feed my family during the year. It’s so satisfying seeing rows of jars full of food you have grown and preserved yourself.

Quillen: When I was a kid and Dad would make us help him work in his garden, I wasn’t a fan! But as I got older, I enjoyed having a vegetable garden and fruit trees, putting up all that bounty in the freezer or in jars to feed my family during the year. It’s so satisfying seeing rows of jars full of food you have grown and preserved yourself.

Gardening gives you a feeling of accomplishment like nothing else: no pressure or judgment, really, nothing to prove. You see the immediate rewards of your work. Physical work is seriously underrated in general as therapeutic, as spiritually uplifting, as character-building. Philosopher Simone Weil wrote extensively about this idea, that physical work done thoughtfully and purposefully offers a kind of transcendent experience where “work occupies its rightful place … it becomes a point of contact between this world and the world beyond.” *

Chapter 16: Tell us about the verses from the ancient Chinese poets that are offered at the beginning of each section. How did you come to choose these poems as doorways into your own poems?

Quillen: I feel an enormous affinity with these ancient women who were obviously so keenly aware of how it was through a connection with nature and words that they could ascend to some higher place spiritually and creatively. When I read these poems that I used, it amazed me to think they were living in a time and place I can’t imagine, over a thousand years ago in some cases, yet their voices sounded real and intimate in my ear as if they were sitting nearby.

Chapter 16: The book is organized into three sections: “Letting Go,” “Interlude: Selah,” and “Holding On.” The first and last sections’ purpose are immediately clear to the reader by the titles alone. Tell me more about the middle section and its role in the book.

Quillen: Music is my favorite thing, my anchor and my refuge! As I mentioned earlier, as I began to come to the end of the elegies and tribute poems to my dad, I began to write about why I loved music so much. And I realized that, even in my writing life, music was going to save the day and point me forward to a new place.

I chose the title for the section as an allusion to the Psalms — the first poems I fell in love with as a child, where I first realized that words could be music, and music could convey like words.

Chapter 16: That love definitely shines through to the reader. As you mentioned, many of the poems in this second section describe joy from singing or dancing. The poems remind us that while our thoughts can be heavy, our bodies have the ability to calm us — even uplift us. Returning to the breath, returning to song, letting go into dance. One of my favorite poems in this section is “Why I Dance”: “I lift my arms out like the climbing hawk / soaring over the still world beneath / moving through pockets of hot and cool air / floating like a note on the evening’s breath.” How is writing about joy both a challenge and a purpose for you?

Quillen: It seems to me, and has been so since I was just a kid in elementary school, that life is full of great sadness and stress and tragic circumstances. I feel all that sadness and darkness very, very deeply. Had I not also been born with the ability and desire to write, I wonder what would have happened to me. I think I would have somehow succumbed to it, physically and mentally, and wouldn’t have had much quality of life. Writing has kept me going, providing a kind of steam valve to allow a lot of negative pressure to escape safely.

Chapter 16: The book deftly discusses grief in a variety of ways. Sometimes the poems directly address those dark moments such as in “First Christmas,” which skillfully collages bits of peppy Christmas carols with the speaker’s disorienting, melancholy thoughts.

Chapter 16: The book deftly discusses grief in a variety of ways. Sometimes the poems directly address those dark moments such as in “First Christmas,” which skillfully collages bits of peppy Christmas carols with the speaker’s disorienting, melancholy thoughts.

“Prayer for Leaving” engages with the grief so eloquently: “Leaving is grieving, one and the same. / What was now isn’t, space and time / full or empty in a new way.” What did you learn about the process of grief that you did not know when you began this book?

Quillen: How dangerous grief is. How insidious. How multi-dimensional it is. If a person has lost a spouse, parent, child, anyone who was a very important part of their life and deeply loved, be prepared and on guard for a tsunami of effects that may appear to have nothing to do with the loss itself. It could be with regard to your health, your money, your job, your personality, your relationships with those still living. Anything.

The other thing I learned: The cliché is true. It does get better with time. Take this opportunity to learn true patience.

Chapter 16: While there is so much wisdom offered in your new book about how to take on grief’s “tsunami of effects,” there is also so much love of life in these poems, such as in “First Memory.” The speaker shares what she saw from her crib, which ends up being a centering memory when times are difficult as an adult. Why do you think poets often avoid writing about joy and focus on tragedy instead?

Quillen: I think it’s just the thing in this post-modern world we are living, writing, and publishing in. It’s the same reason we’ve killed humor in poetry. Poets used to be called “wits” back in the day, but too much joy and humor these days will get you dismissed as a lightweight in a hurry in some circles. I don’t care, fortunately, since I’ve never had to worry about having a “writing career” or anything like that. I can do what I want.

If you are not writing toward wholeness, healing, love, happiness, purpose, wisdom, compassion, and serving others, then what are you doing? And who are you doing it for?

* [From The Need For Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Toward Mankind by Simone Weil.]

Charlotte Pence’s first book of poems, Many Small Fires (Black Lawrence Press, 2015), received an INDIEFAB Book of the Year Award from Foreword Reviews. Her poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction have recently been published in Harvard Review, The Sewanee Review, The Southern Review, and Brevity. A graduate of Emerson College (M.F.A.) and the University of Tennessee (Ph.D.), she is now the director of the Stokes Center for Creative Writing at the University of South Alabama.