‘When You’re Dead We’ll Cherish You Again’

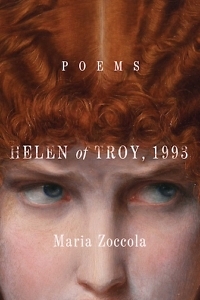

Poet Maria Zoccola brings Homeric mythology to small-town Tennessee in Helen of Troy, 1993

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This review originally appeared on January 7, 2025.

***

Near the end of poet Maria Zoccola’s Helen of Troy, 1993, the book’s titular protagonist addresses the “gods of difficult things” and tries to explain her choices. “i’m out there still, foraging / in the threads of the world for a story I like better / than the one I’ve been telling,” Helen says. “I’m working in the trenches / of my own future, stitching together pieces of bone // and oracle to run down the threat of what might / happen next.”

In this mesmerizing debut, Zoccola merges the mythological and the modern, working a literary alchemy that erupts again and again into startling observation and formal surprise.

Homer’s Helen was the wife of the Greek king Menelaus, and she’s placed at the center of conflict when the Trojan prince Paris claims her as a gift from the goddess Aphrodite, bestowed in exchange for favoring Aphrodite above other goddesses. Paris’ abduction (or seduction) of Helen sparks the decade-long Trojan War.

But Zoccola’s setting does not involve the empires of the Classical world. Instead, we find her Helen living as a restless housewife and mother in Sparta, Tennessee, circa 1993. Her emotionally detached husband may not be a king, but she does refer to him as The Big Cheese.

Zoccola, who grew up in Memphis, shows us Helen in the aisles of Piggly Wiggly, the pews of her local church, the gaudy surrealism of a Chuck E. Cheese birthday party. Helen confronts an overgrowth of kudzu on the porch. She eats hot Krispy Kreme donuts in the car, waiting for her daughter to finish dance class. She watches reruns alongside the husband who bores her. And when a stranger shows her a new possibility, she follows it — away from town and toward her awakened desire.

The women of Sparta have opinions about this. They chime in now and then as a collective voice, recalling the Greek choruses of Classical theatre that gave context and commentary on the actions of the dramas’ main players. Here, in Zoccola’s collection, the Spartan women give their take on Helen and her personal life, always making clear the limits of their patience and compassion. After all, they’ve got their own problems, even though “at one time, truly, / we ourselves were girls.” But “that was many / years ago, and we have since recovered.”

The women of Sparta have opinions about this. They chime in now and then as a collective voice, recalling the Greek choruses of Classical theatre that gave context and commentary on the actions of the dramas’ main players. Here, in Zoccola’s collection, the Spartan women give their take on Helen and her personal life, always making clear the limits of their patience and compassion. After all, they’ve got their own problems, even though “at one time, truly, / we ourselves were girls.” But “that was many / years ago, and we have since recovered.”

Despite the spiky judgments these women make toward Helen, her place in the unfolding story of this small town is already secure among them. “ah, helen,” they assure her, “when you’re dead we’ll cherish you again. we’ll touch your face in our photo albums / and tell each other what you did.”

In this depiction, Homer’s famous description of the “wine-dark sea” becomes the “booze-dark sea.” These kinds of allusions reinforce the epic-poem-size subtext surrounding Zoccola’s Helen as she contemplates her fate on the other side of her transgressive adventure, making her “one / of the stream of girls melting back into our lives, / rib-kicked by the world we wanted so badly to hold / in our hands.”

Zoccola displays a powerful grasp on the voice and perspective of her protagonist, and the result is spellbinding. In an afterword, Zoccola offers some useful context for her project, highlighting the necessity of bringing Helen down to the size of everyday life while also setting her up with a modern woman’s sense of agency. “Our Helen is still unique, set apart, special,” Zoccola writes, “but not special enough to watch the tide of history turn on the axis of her body. Instead she must turn herself, and allow history to turn around her like snow.”

In “helen of troy plants near the mailbox,” Helen recognizes the crucial importance of embracing her own agency: “in my house, we / need more than morning sun. we need green things with a will / to live, / dirt-bound fighters dragging themselves to the light.” This poem is a golden shovel, a poetic form in which a new poem incorporates each word of a line taken from a pre-existing poem, in this case The Iliad. Zoccola includes several golden shovels, deepening her project’s ties to its Homeric origins.

Modern retellings of Classical mythology succeed when their authors have so thoroughly metabolized their source material that, even as those original tales suffuse the modern work, these new stories never feel weighted down by their lineage. Rather, they seem to discover a heightened spirit of freedom. Anne Carson’s strange, unforgettable novel-in-verse Autobiography of Red and Gwen Kirby’s insightful, anarchic story collection Shit Cassandra Saw both come to mind.

Helen of Troy, 1993 certainly belongs in this company. Zoccola’s confident, nuanced use of persona creates a voice that thrums with knowing urgency and fresh observation. She imbues her modern small-town Helen with a resonant sense of timelessness, and the result is an exhilarating debut.

Emily Choate is the fiction editor of Peauxdunque Review and holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Her fiction and essays have appeared in Mississippi Review, storySouth, Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Rappahannock Review, Atticus Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and elsewhere. She lives near Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.