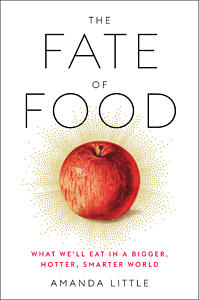

Where Food Meets Science

Amanda Little’s The Fate of Food considers the future of our global table

Investigative journalist and Vanderbilt University Writer-in-Residence Amanda Little traveled to Kenya, China, Norway, India, and Israel (as well as less exotic places like Wisconsin, New Jersey, and Arkansas) to research The Fate of Food. The word “fate” is often paired with the word “dire,” and Little provides plenty of facts to inspire fear about our prospects on this planet we’ve abused.

For instance, she writes this: “In the past three decades the world has lost a third of its arable soil because of erosion caused by mechanical tillage and damage from industrial chemicals.” And this: “[T]he U.S. Geological Survey has predicted that more than three-quarters of the Southwest … will be in a state of permanent drought by midcentury.”

Hovering over this project is climate change, a term The Guardian recently called “rather passive and gentle when what scientists are talking about is a catastrophe for humanity.” The author visits orchards in Wisconsin owned by a man who lost six million apples and $1 million when the temperature dipped below freezing for four hours in mid-May 2016. That year, she writes, “deadly floods swept Texas; the Antarctic ice shelf cracked; portions of India reached a record-breaking 128 degrees Fahrenheit; forest fires burned swaths of Alaska; twenty-eight inches of snow inundated New York City in two days.”

But while The Fate of Food is a hard reality check, it’s always scanning the horizon for hopeful solutions to the unfolding disaster. Its subtitle, after all, is What We’ll Eat in a Bigger, Hotter, Smarter World — emphasis on that last adjective. Like the robots that target weeds in Arkansas cotton fields, Little zeroes in on the inventors and investors who are applying radical thought and technology to the mess we’ve made of the food supply. A reader may despair about the state of arable land at the beginning of a chapter and then find reasons for optimism pages later in adaptations that farmers are making to no-till fields.

Little immerses herself, and us, in the details of her research. “I’m slouched in the backseat next to an open window, taking in the smells of burning maize husks, plowed earth, animal dung, diesel fumes, and eucalyptus trees,” she writes of a trip to the Kenyan countryside to visit subsistence farmers who are using drought-resistant corn seeds. “Three days have passed since my last meal, a bowl of goat stew that threw my first-world digestive system into a violent revolt.”

She proceeds with an essay that explores both sides of the genetic-crop debate and Monsanto’s role in it and then circles back to the farmers on the frontlines. She visits a Kenyan couple with nine children who live on 1.5 acres. Their father, she writes, “takes my hand and says, ‘If, through the almighty God, you are sympathetic, do nothing but take one.’ … Too much time passes before I understand that Robert has asked me to raise one of their children in the United States.”

She proceeds with an essay that explores both sides of the genetic-crop debate and Monsanto’s role in it and then circles back to the farmers on the frontlines. She visits a Kenyan couple with nine children who live on 1.5 acres. Their father, she writes, “takes my hand and says, ‘If, through the almighty God, you are sympathetic, do nothing but take one.’ … Too much time passes before I understand that Robert has asked me to raise one of their children in the United States.”

Little visits a salmon farm in Norway under siege by sea lice, where a robot named Sting Ray is deployed to fry the parasites without harming the fish. She’s with Alf-Helge Aarskog, the CEO of Marine Harvest, who owns the world’s largest salmon fishery. He’s trying a number of ways to protect his living product from damage, including “Eggs”: cages 100 feet wide that look like white UFOs in the water and can hold 200,000 fish. Here’s the economical personality profile the author provides of her host: “In the many hours I spend with him during my visit and by phone thereafter, he laughs exactly once.”

A visit to the United States’ largest vertical farm — a factory for leafy greens set in an old steel mill in Newark — reminds Little of the 1972 sci-fi classic Silent Running, but science fiction steadily succumbs to reality as the book progresses. At a California laboratory that grows edible meat from cells, she watches a video of the cultured beef. “I see what looks like a smear of beef carpaccio on the bottom of a petri dish. It’s perfectly still — and then it spasms,” she writes. “I’d been expecting it, but I audibly gasp.” Inevitably, her itinerary includes a lab that’s experimenting with a 3-D printer to make food.

This is science for everyone’s sake, and Little’s voice is reliably curious and informed, skeptical but receptive. Her attention to human details clarifies the crucial information she’s delivering. In the Wisconsin orchard that was devastated in 2016, she and the orchardist come upon a dying tree, black and leafless, but resplendent with apples. “She knows her time is up so she’s trying to pump a ton of apples out there because that’s her biological purpose,” the orchardist explains.

“I feel oddly hopeful witnessing this final act — proof positive of the plant’s primordial will, against increasing odds, to live on,” Little writes.

Formerly the books editor at The Commercial Appeal in Memphis, Peggy Burch is now the community engagement editor at The Daily Memphian and a member of the Humanities Tennessee Board of Directors. She holds a master’s degree in English literature from the University of Mississippi.