Wide Awake

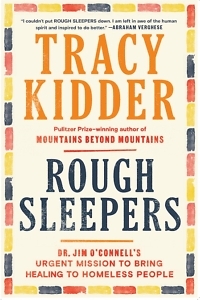

Rough Sleepers is a compelling narrative and call to action

Several times throughout Tracy Kidder’s nonfiction book Rough Sleepers, he references the story of Sisyphus to describe the work of homeless care providers in Boston. The book follows Dr. Jim O’Connell and a street medical team for five years as they battle a slew of systemic barriers to health care for people living on the streets.

In case the story isn’t familiar, Sisyphus was a figure in Greek mythology who cheated death, and as punishment he spent eternity rolling a giant boulder up a hill only to have it fall back down again. It’s a feeling many working with unhoused people come to recognize — not so much cheating death as the feeling that the journey toward getting people into housing is often one step forward, two steps back.

Working in homelessness probably wouldn’t have been O’Connell’s first choice, but exposure to people in need made a difference in his trajectory. In 1985, after he graduated from Harvard Medical School and performed his residency at Massachusetts General Hospital, the chief of medicine asked O’Connell to help create a health program just for people living on the streets in Boston. He has been there ever since, with a cast of other helpers, attempting to provide health care to patients whose needs often don’t fit into the rigid mold of the U.S. health system.

Through O’Connell, Kidder gets an up-close view into the moments when the boulder feels the heaviest. People he treats sometimes get sicker. They die. They get into housing and lose housing. Others ride an endless rollercoaster of street life. His focus is on those who, for various reasons, don’t typically spend nights at city shelters. So-called “rough sleepers” often bed down in wooded areas and in tents spread across the city. There are moments of relief, respite, and victory in O’Connell’s work, but these are always celebrated briefly and often overshadowed by the next person who needs help.

The parallels between the tragic narratives in Boston and the realities on the streets in Tennessee’s urban areas are obvious, especially in the realm of health care. In one scene in the book, O’Connell happens upon one of his patients who’d been discharged from a hospital. The man is found in his hospital gown on the streets of the city. It’s hard for anyone to get well and stay well without a roof over their head.

The parallels between the tragic narratives in Boston and the realities on the streets in Tennessee’s urban areas are obvious, especially in the realm of health care. In one scene in the book, O’Connell happens upon one of his patients who’d been discharged from a hospital. The man is found in his hospital gown on the streets of the city. It’s hard for anyone to get well and stay well without a roof over their head.

Kidder, who won the Pulitzer Prize for his The Soul of a New Machine, has a unique ability to detail an individual life like O’Connell’s and make it part of a broader truth. He shows how much impact even one dedicated person can have on many lives. O’Connell, revered as something of a saint in homelessness circles in Boston, talks of the changing of the guard there, of folks he cared for being replaced by a bevy of new folks on the street with new issues. He, too, will ultimately be replaced by someone with a passion for the same grueling work.

Yet Rough Sleepers makes it clear that the needs O’Connell has dedicated his life to addressing cannot be erased by a few saintly individuals. The program he built is the largest of its kind in the nation, exceptional in its scope and mission, but Kidder points out that even this massive effort hasn’t made the dent in overall homelessness O’Connell envisioned. Near the end of the book, Kidder outlines part of a speech O’Connell gave to important donors at a gala in 2018.

“I like to think of this problem of homelessness as a prism held up to society, and what we see refracted are the weaknesses in our heath care system, our public health system, our housing system, but especially in our welfare system, our educational system, and our legal system — and our corrections system,” O’Connell said. “If we’re going to fix this problem, we have to address the weaknesses of all those sectors.”

Kidder follows with more context for O’Connell’s remarks, noting the staggering inequality between Black and white residents in Boston regarding homelessness, as well as the toll taken by economic anxiety:

Homelessness was fed by racism, income inequality, and a cascade of other related forces. These included insufficient investments in public housing, as well as tax and zoning codes that had spurred widespread gentrification and driven up rents. Many poor and moderately poor Americans lived with the fear of losing housing, which can itself harm bodies and minds as well as social relations in families.

These observations still apply far beyond Boston. In short, while O’Connell is not the only one out there pushing the boulder up the hill, it’s going to take a lot more work and support from all of us to reach the top.

Amanda Haggard is a freelance writer, editor, and journalist living in Nashville. For the past decade, she’s written about homelessness, books, music, politics, food, and everything in between. She is the co-editor of Nashville’s street newspaper The Contributor.