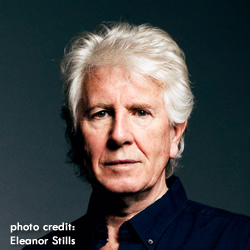

Wild Ride

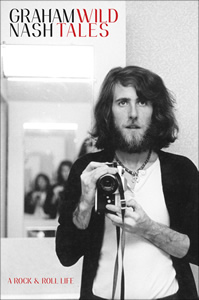

Rocker Graham Nash talks to Chapter 16 about his new autobiography, Wild Tales, his political activism, and his often tumultuous life as a member of both The Hollies and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young

“That sound happened in less than a minute,” says Graham Nash. He’s talking to Chapter 16 about the first time he sang with David Crosby and Stephen Stills in August of 1968. Incredibly, the sound that gave the world hits like “Carry On,” “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes,” and “Teach Your Children”––harmony songs that defined an era––emerged fully formed.

The sound had precedents, of course. There were The Louvin Brothers and The Everly Brothers, vocal duos who had influenced a generation of British and American musicians along with Nash, who grew up near the English industrial city of Manchester. There was also The Hollies, a band that Nash himself had formed with childhood friend Allan Clarke. The band produced massive hits in the U.K. and the U.S. during the early sixties, songs such as “Carrie Anne” and “On a Carousel,” whose defining feature was Nash’s razor-sharp high harmony vocal.

In his new memoir, Wild Tales: A Rock & Roll Life, Nash documents his time with both Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and The Hollies and he doesn’t gloss over the ugly stuff––most notably Crosby’s long descent into drug madness and Nash’s own ongoing attempt to understand sometime bandmate Neil Young. Nash is still performing with CSN&Y, as well as doing solo shows and duo gigs with Crosby. A two-time Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee and an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE), Nash also finds time for political action and photography––his work in early digital fine-art printing is considered groundbreaking. Nash recently took the time to speak at length with Chapter 16 by phone.

(A brief note: the conversation that follows is not G-rated. Fans of Graham Nash will find it unsurprising, but readers sensitive to graphic language might prefer to read one of the many other interviews, reviews, articles, poems, or essays on offer at Chapter 16.)

Chapter 16: So many rock biographies seem to have an axe to grind. Wild Tales, on the other hand, is dishy but never mean-spirited. Did you work to achieve that balance, or are you just a nice guy?

Chapter 16: So many rock biographies seem to have an axe to grind. Wild Tales, on the other hand, is dishy but never mean-spirited. Did you work to achieve that balance, or are you just a nice guy?

Nash: I think it’s both. That’s the kind of person I am. I try to do my best. And of course when you’re writing your autobiography you can’t lie about anything––what good is that? I wanted to tell the truth—a truth—and not hurt anybody. That’s why the last line of the book is “That’s how I remember it.” In a really strange way, we all have our different truths.

I did not have an axe to grind at all—I’m not crazy about weapons of any kind. But I did want to tell what happened. And one of my main concerns was my friend David [Crosby] because I was pretty honest and brutal about the way his slide into drug madness affected me on a musical level, a psychological level, and an emotional level. So he was the one I was most worried about, and he told me not to change a word. He owns up to what he did.

Chapter 16: You grew up idolizing The Everly Brothers, and they would eventually become your colleagues. Can you tell me how your initial impressions of them, on vinyl and in photographs, compared with the actual guys?

Nash: They were incredibly important in my life. I had never heard two voices sing together like that. I was making music with my friend Allan Clarke, who had formed the Hollies with me when were fourteen, fifteen, sixteen years old. But with the Everly Brothers, something was very different. It must be DNA. It must be that they were brothers and grew up listening to each other talk over the breakfast table, as brothers do.

I just recently re-listened to a CD of thirty-two outtakes from their stuff. Every entrance, every breath, and every way that they finished a sentence together—they were completely remarkable. They were also fine as people. They were very gentle with me, very courteous and encouraging, and they changed my life for the better.

I think that when David and Stephen and I blend our voices together, we try to be as accurate as The Everly Brothers were. We needed to be one voice, and that’s the thing about them. Even though there were two singers, they were one voice. When David and Stephen and I sing together, we try to do the same thing. It was an astonishing thing to discover. When we first sang together, that sound—whatever that sound is—happened in less than a minute.

I think that when David and Stephen and I blend our voices together, we try to be as accurate as The Everly Brothers were. We needed to be one voice, and that’s the thing about them. Even though there were two singers, they were one voice. When David and Stephen and I sing together, we try to do the same thing. It was an astonishing thing to discover. When we first sang together, that sound—whatever that sound is—happened in less than a minute.

Chapter 16: Some rock-and-roll rifts never heal, but you’ve been a part of some legendary rock-and-roll reconciliations. You had a fourteen-year separation from Allan Clarke but eventually made up and performed with him again. The history of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young is one feud after another, yet you’re often seen as the glue that binds the highly volatile personalities together. Where do your negotiating skills come from?

Nash: First of all, I’m just glad to be alive. I grew up when World War II still had three years to go. There were times that my mother and father didn’t know if the house was going to be there tomorrow or whether we’d be alive tomorrow. And when you grow up under those circumstances, it gives you a certain strength and a certain perspective. I personally think, just as an aside, that—God forbid—America had ever been bombed like England was bombed, they would have a different opinion about these preemptive wars that we keep waging.

My point is that when your very life is in jeopardy and life is fragile, you can stand anything. It’s all bullshit, it’s all meaningless. The only meaningful thing about David and Stephen and I is our friendship and the music that we make. That’s what’s going to last beyond our physical bodies. How many people did you make smile? How many people did you make think? How many people’s hearts did you touch? That’s what’s important. The rest is just meaningless.

Chapter 16: Has dealing with temperamental bandmates made you a better political activist?

Nash: Absolutely. No question about it. When you’re trying to find your way through the chaos of three, and when you add Neil and Joni [Mitchell], five incredibly strong, opinionated people who look at the world with different eyes than most people—when you weed your way through all that, you become good at negotiating; you become good at compromise. I want everyone to win. Why not?

Nash: Absolutely. No question about it. When you’re trying to find your way through the chaos of three, and when you add Neil and Joni [Mitchell], five incredibly strong, opinionated people who look at the world with different eyes than most people—when you weed your way through all that, you become good at negotiating; you become good at compromise. I want everyone to win. Why not?

Chapter 16: So after dealing with Steve Stills, Ted Nugent isn’t a big deal?

Nash: No, he’s just an idiot. God bless him, he stands up for what he believes, but I completely disagree with him on so many points. It’s happening right now with the Tea Party and Ted Cruz and Ron Paul—they’re attacking Obama on every single thing: the length of his fingernails, how many sheets of toilet paper he uses. None of it helps, particularly with the situation in the Ukraine.

Chapter 16: Where are you putting most of your political energy these days?

Nash: I’m writing songs about it. I’m so disappointed that you can probably buy a congressman for the price of a good car. The more that comes out about these people—it’s sad to me. I don’t like the two-party system. I don’t see why there isn’t a green party that has as much chance of winning as the Democrats and Republicans. But I’m a Democrat. I would be ashamed to be a Republican with their war on women and their war on immigrants and their fight against Obama and standing in the way of everything he tries to do to make it better for the American people.

I’ve supported Obama; I worked very hard to get him elected, and so did David. But I don’t agree with everything that he’s doing. I certainly don’t agree with the NSA recording this conversation that we’re having right now. I don’t agree with his stance on whistleblowers. He talks a good story regarding Bradley Manning and Edward Snowden, but we need whistleblowers, and they should be protected. “We need to support whistleblowers and encourage them, except those two”—he talks a good story but I have disagreements with Obama, and he knows it. But he has tried his best, and he’s a very, very bright man, and he has a wonderful soul, and it must be insanely difficult to be president of the United States.

I’ve supported Obama; I worked very hard to get him elected, and so did David. But I don’t agree with everything that he’s doing. I certainly don’t agree with the NSA recording this conversation that we’re having right now. I don’t agree with his stance on whistleblowers. He talks a good story regarding Bradley Manning and Edward Snowden, but we need whistleblowers, and they should be protected. “We need to support whistleblowers and encourage them, except those two”—he talks a good story but I have disagreements with Obama, and he knows it. But he has tried his best, and he’s a very, very bright man, and he has a wonderful soul, and it must be insanely difficult to be president of the United States.

Obama admits to smoking dope when he was a kid. Most bright people have tried it at some point. When other states look at Colorado [after legalizing recreational marijuana]—this year alone they made millions and millions of dollars because it’s being taxed properly. I watched Lawrence O’Donnell last night, and he said something very, very profound and very simple. He said, why would you not tax marijuana and legalize it the same way that we do with tobacco, which kills about 300,000 Americans a year. Or alcohol, which kills many, many thousands of people—not only from alcoholism but from drunk driving. I don’t know one person that died from smoking dope. Not one.

Chapter 16: In Tennessee you hear rumors that the tobacco companies are pretty much ready to go should marijuana become legal here and in Kentucky.

Nash: Thirty years ago we knew that they had trademarked “Maui Wowie” and “Kush” They’ve got all the trademarks and probably have the packaging already. They’re not stupid. And they know that people are hip to how bad tobacco really is, so they’ll just change their profits to dope.

Chapter 16: Do you look back on your career and see a golden age, a time before the music-business hassles and rifts with bandmates and political disappointments, when anything seemed possible?

Nash: It was probably the late ’60s, early ’70s with David and Stephen. From 1962 when we formed The Hollies, and we recorded in 1963. Our first record got into the top twenty, and we never looked back. But when I thought that I’d run my course with The Hollies—in terms of differing musically about what they wanted to do—and then found David and Stephen, it just leapfrogged into insanity. And it’s still going. Somebody told me the other day that they heard “Teach Your Children” in Katmandu! I’m thinking, holy shit, the music is really the most important part of our relationship. No question about it.

But the music business has changed drastically. Everybody tried to tell the record companies that this Napster thing is happening and this digital-downloading is happening, and most of the artists are putting only two great tracks on the record and filling it in with lesser music, and the kids are saying. “Why should I pay eighteen dollars for a CD when I only want these two? I’ll just download these two.” We told them that this train is coming and they better move or they’ll get run over, but they took no notice, and now look what happened. But playing live—there’s nothing like it. The music that I’ve made in my life with my friends has pulled me through insanity.

But the music business has changed drastically. Everybody tried to tell the record companies that this Napster thing is happening and this digital-downloading is happening, and most of the artists are putting only two great tracks on the record and filling it in with lesser music, and the kids are saying. “Why should I pay eighteen dollars for a CD when I only want these two? I’ll just download these two.” We told them that this train is coming and they better move or they’ll get run over, but they took no notice, and now look what happened. But playing live—there’s nothing like it. The music that I’ve made in my life with my friends has pulled me through insanity.

Chapter 16: You write that your Crosby, Stills, & Nash song “Marrakesh Express” was a breakthrough for you. You were moving away from simple love songs toward a more impressionistic, expansive way of singing about the world. Are there any young songwriters today whom you see going through a similar transformation?

Nash: Jason Mraz is the real deal. Jonathan Wilson is also the real deal. They’re writing songs that have a reason for existence, and they’re trying to touch your heart and engage your mind. I’m working on a project with a friend of mine called Spencer Proffer. It’s an album of Jimmy Hendrix songs done acoustic. Jason Mraz contributed “Angel” by Jimmy, and me and Crosby harmonized with him, and it’s fucking beautiful.

[Updated on August 15, 2014, with new event details.]

Paul Griffith is a freelance writer/musician based in Nashville whose interests include popular culture, religious history, and food and dining. Paul’s drumming can be heard on recordings by k.d. lang, Todd Snider, and many others.