Without Fear or Condescension

Autistic actor Mickey Rowe celebrates difference

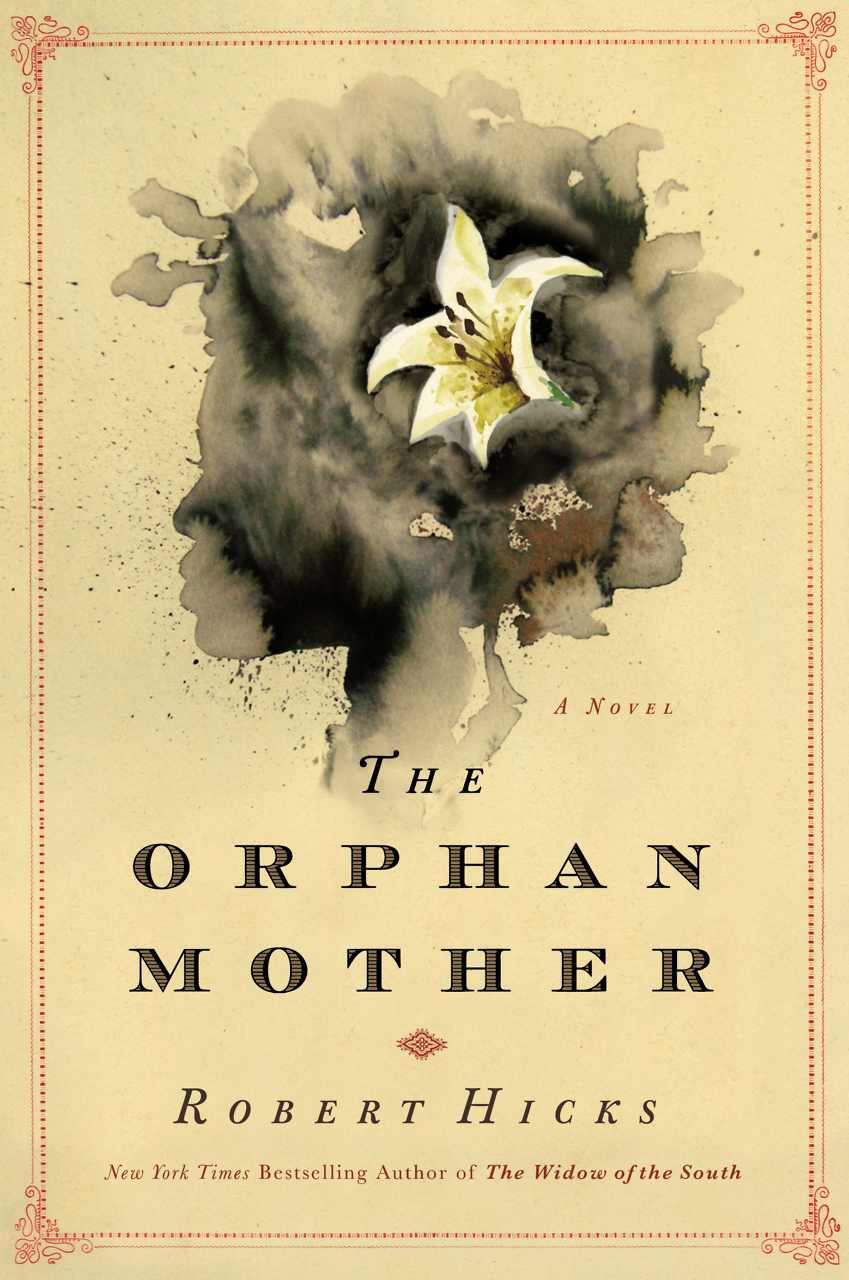

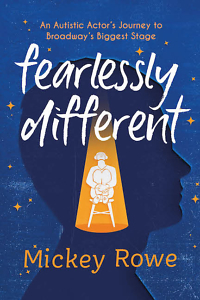

Fearlessly Different: An Autistic Actor’s Journey to Broadway’s Biggest Stage is Mickey Rowe’s memoir of growing up with autism and his barrier-breaking career. Most notably, Rowe starred as Christopher Boone in the Tony Award-winning play The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. He was the first autistic actor to portray an autistic character on Broadway.

It is imperative to note that Rowe recognizes differences in a broad manner; he even makes room for differences of perspective in how others might recall the events chronicled in this book. Much of Rowe’s childhood was spent in the company of his own thoughts. As he guides us back through his interior quiet world, we discover that he responds with grace, not bitterness, to the demeaning humor and outright disdain that surrounded him. Reflecting on his mother’s early parenting, he says, “Perhaps she was actually more disappointed in herself as a mother than she was in me as a son.”

It is imperative to note that Rowe recognizes differences in a broad manner; he even makes room for differences of perspective in how others might recall the events chronicled in this book. Much of Rowe’s childhood was spent in the company of his own thoughts. As he guides us back through his interior quiet world, we discover that he responds with grace, not bitterness, to the demeaning humor and outright disdain that surrounded him. Reflecting on his mother’s early parenting, he says, “Perhaps she was actually more disappointed in herself as a mother than she was in me as a son.”

But it was also in this quiet that he birthed a vivid imagination. He grew up in Seattle and recounts the childhood years he spent envisioning himself as a pirate as he sailed on a real homemade raft in the Salish Sea. Unable to communicate with adults, he found the marine life to be welcome conversation partners through touch and sound:

I marveled at the rough sandpaper of starfish, the playful otters that dared to poop on my fearsome pirate poop deck, and every so often the occasional baby octopus! … I relished in every moment of animal encounter. My fellow humans seemed so obsessed with me learning to communicate in a way that was convenient for them, but the sea animals didn’t make speaking a requirement for interaction with me. They already understood.

Each chapter of Fearlessly Different begins with an epigraph from a well-known historical figure. These include the likes of Nelson Mandela, Helen Keller, and Mahatma Gandhi. The epigraphs serve to underscore perseverance or other themes discussed in the subsequent sections. However, these words are sometimes used for their irony. For instance, one chapter begins with a quote from Kate Winslet — “Play a mental, win an Oscar” — followed by Rowe recalling his challenges as a disabled actor auditioning for disabled roles. It is not his playing a “mental” that is an issue, so much as his being one.

Throughout the book, readers may be introduced to new language that is native to the discussions around disability. Following the proliferation of the word “blackface,” the suffix “face” has come to broadly indicate the harmful appropriation of cultural and racial identities. Rowe uses the term “cripface” to refer to nondisabled individuals appropriating the experience of disabled people for monetary gain or cultural cachet. “But having nondisabled actors in cripface wins awards, earns critical acclaim, and makes money, so Hollywood is more than happy to tune out the disability community and let it continue,” Rowe writes.

Throughout the book, readers may be introduced to new language that is native to the discussions around disability. Following the proliferation of the word “blackface,” the suffix “face” has come to broadly indicate the harmful appropriation of cultural and racial identities. Rowe uses the term “cripface” to refer to nondisabled individuals appropriating the experience of disabled people for monetary gain or cultural cachet. “But having nondisabled actors in cripface wins awards, earns critical acclaim, and makes money, so Hollywood is more than happy to tune out the disability community and let it continue,” Rowe writes.

While the language may be newer, the occurrence of such discrimination is not. Rowe highlights the fear surrounding disability that exists in American culture and how that in turn leads to nondisabled actors being cast as disabled characters. The only time, he suggests, that disability is acceptable in the mainstream is when it can be easily shed, as when an actor steps out of a role.

By way of Rowe’s noteworthy storytelling, we return to the theatrical experiences that helped formulate his philosophy of the arts. It was not only that the stages were filled with texture and color and voices, but that speaking was not a requirement for engagement. In essence, theatergoing seemed made for his disability, since the actors spoke to him and everyone else like humans, without condescension. This, Rowe asserts, is how all theater should be — honest and accounting for the humanity of the audience.

Rowe tells his story with a tone of activism. He weaves in urgent facts about issues like rates of unemployment among autistic college graduates, which he cites at 85%. Later, he returns to statistics to emphasize society’s discomfort with disability: “It’s why an estimated 67 percent of pregnancies that receive a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome are terminated.” It is the existing discrimination that shapes what we see on the screen and stage and vice versa.

Fearlessly Different is for people with autism and those who love them. But it is also for those who do not see the world through measures of sensory overload and who perceive themselves to be “normal.” This book calls us away from fear and pity and toward building a radical new world, shaped in celebration of differences.

Kashif Andrew Graham is a writer and theological librarian. He enjoys writing poetry on his collection of vintage typewriters. He is currently at work on a novel about an interracial gay couple living in East Tennessee.