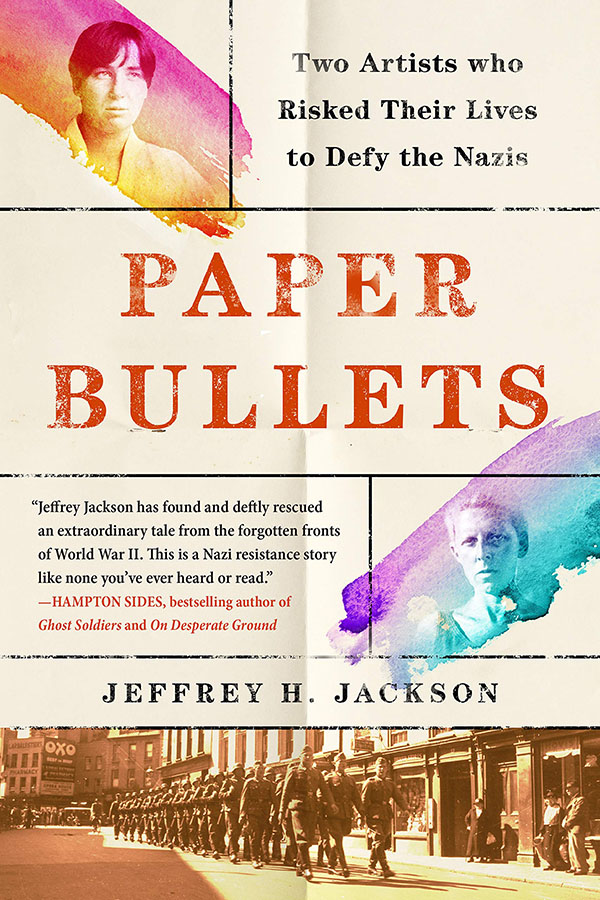

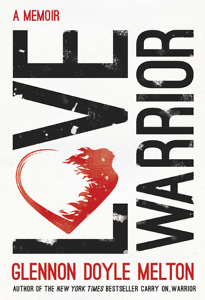

Woman / Warrior

Glennon Doyle Melton talks with Chapter 16 about the cultural biases that inhibit authentic love

“What if pain—like love—is just a place brave people visit?” asks Glennon Doyle Melton, the popular blogger of Momastery, bestselling author, and founder of Together Rising, a nonprofit that leverages crowd-sourced aid to heal women. Melton coined the term “brutiful” to describe the combination of ecstatic joy and heart-wrenching pain we encounter on any day we allow ourselves to be truly open to the experiences of ourselves and others. In her new memoir, Love Warrior, Melton traces the inescapable loneliness of a woman afraid to face her own pain as she tells the story of her early childhood, her adolescent addictions, her fortuitous writing career, and the crisis in her marriage that made her rethink it all and return to the most fundamental question: how do we truly love ourselves and others?

Melton’s narrative voice, full of candor and grace, is easy to love. Not wanting to squander our trust or waste our time, she addresses hard truths about sexism, intimacy, desire, and self-denial, inviting us into a more honest and integrated life. Melton describes Love Warrior as the story of her “unbecoming,” but it resonates like an origin myth.

In advance of her Nashville appearance—an onstage conversation with novelist Ann Patchett—Melton answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: In Love Warrior, you share memories of learning at an early age that “pretty” warms people while “smart” cools them. What can parents do to help their daughters counter internalized sexism?

Melton: The best thing we as parents can do is help our girls see and identify sexism. Talk to them about it. Point it out, and have an open conversation. My girls know when an adult tells them to “smile,” that’s sexist. We’ve talked about how the world is uncomfortable with a girl who’s not smiling. They are aware of this. My daughter recently asked me when looking at a magazine, “Why do all these girls look the same?” We talked about how the world wants to see pretty and thin women in magazines, and she decided to write a petition to magazines asking them to include women of different colors and sizes. Her petition went viral on the Internet. My girls get angry at what they see and they try to do something about it.

There’s a lot of poison in our culture, and girls either get sick or get angry—these are really our only two options. I want to teach my girls to be activists so they can change the system instead of allowing the system to change them! Internalizing these poisons make us sick—keeping our anger in makes us sick. We can all counter this internalized sexism by showing our girls how to change the culture rather than the culture changing them.

Chapter 16: From a young age, you became aware of what you call your “Representative”—another self you project to others as a shield. Some of your most poignant insights come in recognizing the Representative’s shapeshifting ability to keep you from seeing and living the truth. How are you currently making peace with your Representative?

Melton: We all have representatives. We put on our armor before we go out into the world. What’s important to me right now is to have at least a few people for whom I do not need to have a representative. I even had a representative for my husband, but I no longer do. Now I make sure my outside and my inside match all the time. So I tell the story of my inside and my outside. When I’m angry I don’t say I’m fine; I say I’m angry. As I talk about in Love Warrior, I share my feelings; I don’t keep them in. We call that sharing our feelings from the inside on the outside. It’s what integrity means—integrated. So with at least a few people in my life I have this integration, which is what I would wish for all of us. Otherwise we live a very lonely, disconnected life.

Chapter 16: Much of Love Warrior dissects the loneliness at the center of marriage, and you recently announced on your blog that you and your husband have separated. How did writing this book affect your feelings about your own marriage?

Melton: Writing Love Warrior helped me appreciate my marriage. When you go through a trauma, all you’re doing is surviving it. The beauty of writing is you have the opportunity to examine the trauma and writing Love Warrior did just that, and it gave Craig and me the chance to help one another to become more whole, and now our relationship is beautiful and complete. We went as far as we could go and choose to continue our paths separately as braver, kinder, more complete human beings, which is why I’ll always consider my marriage a success.

Chapter 16: Your writing captures your own spiritual journey in a way that has made you a sought-after speaker in churches, but this book tells the story of your break with institutional Christianity. How would you describe your beliefs today?

Melton: I didn’t break up with Christianity, but what I don’t do is look to the church to tell me what God thinks. I love the beauty I find in church, and I go to church for a cool perspective on Jesus Christ and God, and, yes, for the beauty I find there, but I don’t need the church to be a middle man between me and God. I don’t believe in religion and the rules religion imposes on us to be closer to God. I believe in church, and I believe in God, but I don’t believe that one person or institution knows any more about God than anyone else. I don’t need to go to church to “feel” God or to feel closer to God. I go to be in the presence of a loving community.

Melton: I didn’t break up with Christianity, but what I don’t do is look to the church to tell me what God thinks. I love the beauty I find in church, and I go to church for a cool perspective on Jesus Christ and God, and, yes, for the beauty I find there, but I don’t need the church to be a middle man between me and God. I don’t believe in religion and the rules religion imposes on us to be closer to God. I believe in church, and I believe in God, but I don’t believe that one person or institution knows any more about God than anyone else. I don’t need to go to church to “feel” God or to feel closer to God. I go to be in the presence of a loving community.

Chapter 16: You are very honest about how baffling love and sex can be. What would you say to your ten-year-old self—or to your own daughters—that might put the discovery of love and sex on the right path?

Melton: What I learned is that at a young age we are all a combination of body/mind/spirit, and what happens to young girls in our culture is we get so many confusing messages about our bodies that we start to objectify ourselves. We end up caring more about being desired than we do about desiring. We worry more about being wanted than wanting. We worry more about what we look like than who we are, how we feel, how we’re seen as human beings. I want my girls to be whole, so I remind them their bodies can be trusted. I tell them that their bodies are as holy as their spirits and they can both offer and receive love, that their bodies are, in fact, vessels of love. I remind them their value is not based on the shape of their bodies, but on their ability to give and receive love.

Chapter 16: Together Rising is a nonprofit you founded to help people with immediate needs in the wake of individual crisis or international disaster. How did you realize you had the power to change people’s outcomes this way?

Melton: Everyone has the power to change people’s outcomes! Somehow many of us have learned the misconception that giving is only something the rich or powerful can do, so we don’t do it, but in fact at Together Rising we proved that all it takes for change is for ordinary people to come together with the desire to make a difference. We’ve raised five million dollars! Even when we can’t do “great” things, we can each do one small thing with love, and together these simple efforts can change the world.

Beth Waltemath graduated with a degree in English from the University of Virginia and worked at both Random House and Hearst magazines before leaving publishing to attend Union Theological Seminary in New York City. A Nashville native, she now lives in Decatur, Georgia.