Women of the Past Come Alive

Tennessee Women: Their Lives and Times sheds new light on the history of the Volunteer State

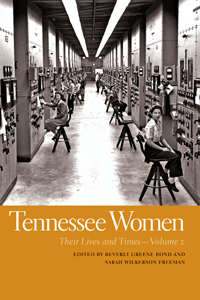

With the second volume of Tennessee Women: Their Lives and Times, editors Beverly Greene Bond (University of Memphis) and Sarah Wilkerson Freeman (University of Arkansas) have published the highly-anticipated companion to their first book by the same title, which appeared in 2009. This new collection includes sixteen essays by scholars who together cover the contributions made by Tennessee women to the history of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

In the nineteenth-century portion of the book, Beverly Bond writes, “We are introduced to enslaved women who struggle to locate public and private spaces where they can express their personhood, to free white women who challenge traditional perceptions of womanhood, and to black and white women who use their presence in public spaces to frame or reframe social and political ideology.” From the beginning, then, readers understand that this volume pays attention to all Tennessee women and not simply those from one group or another. Bond’s own compelling essay, “’Ma … Did not make a good slave’: African American Women and Slavery in Tennessee,” opens the doors of Tennessee’s slave quarters and plantation houses and reveals the ways in which nineteenth-century women in Tennessee fought for some autonomy for themselves and their children. “I believe they were afraid of her or thought she was crazy,” the daughter of a slave named Fannie recalled years later as she described her mother’s interactions with the plantation owners on behalf of herself or her children.

In the nineteenth-century portion of the book, Beverly Bond writes, “We are introduced to enslaved women who struggle to locate public and private spaces where they can express their personhood, to free white women who challenge traditional perceptions of womanhood, and to black and white women who use their presence in public spaces to frame or reframe social and political ideology.” From the beginning, then, readers understand that this volume pays attention to all Tennessee women and not simply those from one group or another. Bond’s own compelling essay, “’Ma … Did not make a good slave’: African American Women and Slavery in Tennessee,” opens the doors of Tennessee’s slave quarters and plantation houses and reveals the ways in which nineteenth-century women in Tennessee fought for some autonomy for themselves and their children. “I believe they were afraid of her or thought she was crazy,” the daughter of a slave named Fannie recalled years later as she described her mother’s interactions with the plantation owners on behalf of herself or her children.

Gary Edwards’ essay, “Migrants, Clothiers, Farmers: The Lives and Labors of Antebellum Female Plainfolk,” focuses on the “common white women in farming households” so often absent from the narrative. Edwards reveals the restlessness of these women and their efforts to improve family conditions. In the process he helps to dispel the enduring stereotype identifying westering women as shrinking violets, reluctant to take chances, always clinging to the arm of husband or father. Edwards introduces women such as Levinah Murphy, part of the ill-fated Donner Party, and Julia Montgomery, the eldest of four orphans who raised her siblings to adulthood on her own. As Edwards concludes, these yeowomen “touch the very heart of our common humanity.”

The twentieth-century portion of the book, writes Sarah Wilkerson Freeman, reveals “an incredible tenaciousness on the part of many Tennessee women, across time and racial and religious spectrums, to lead by example and inspire a right and righteous faith in human equality and dignity.” The essays included here introduce the new opportunities available to women during the twentieth century, but they are also clear about the costs accompanying those changes. In “I Am Mrs. America: The ‘Secret City’ Women of Oak Ridge, Tennessee, during World War II,” Russell Olwell discusses the role women played on the Manhattan Project. Unlike the familiar Rosie the Riveter of West Coast shipyards, who temporarily filled jobs vacated by soldiers and sailors at war, Oak Ridge women were hired specifically for the jobs they held, and after the war they remained at work in much higher percentages than most wartime female workers did. The health risks associated with radiation exposure were not unknown to doctors in the 1940s, but workers were seldom made aware of them, and many experienced symptoms that became persistent and were sometimes fatal.

The twentieth-century portion of the book, writes Sarah Wilkerson Freeman, reveals “an incredible tenaciousness on the part of many Tennessee women, across time and racial and religious spectrums, to lead by example and inspire a right and righteous faith in human equality and dignity.” The essays included here introduce the new opportunities available to women during the twentieth century, but they are also clear about the costs accompanying those changes. In “I Am Mrs. America: The ‘Secret City’ Women of Oak Ridge, Tennessee, during World War II,” Russell Olwell discusses the role women played on the Manhattan Project. Unlike the familiar Rosie the Riveter of West Coast shipyards, who temporarily filled jobs vacated by soldiers and sailors at war, Oak Ridge women were hired specifically for the jobs they held, and after the war they remained at work in much higher percentages than most wartime female workers did. The health risks associated with radiation exposure were not unknown to doctors in the 1940s, but workers were seldom made aware of them, and many experienced symptoms that became persistent and were sometimes fatal.

Finally, in “’Small Places Close to Home’: Gender, Class, and Civil Rights Work—Mildred Bond Roxborough and the NAACP,” Zanice Bond discusses the grass-roots reform efforts undertaken by Mildred Bond Roxborough, first in 1935 as a nine-year-old selling issues of Crisis, the NAACP magazine, and continuing to the present day. Bond uses events from Roxborough’s life to set out the difficulties African-Americans, and particularly women, faced in the twentieth century as they attempted to organize for reform and establish NAACP chapters. Threats of physical violence drove Roxborough’s family from Brownsville in the late 1930s, and though she never again lived in Tennessee, the lessons she learned there stayed with Roxborough and encouraged her life’s work. As Bond’s essay makes clear, Roxborough represents the hundreds, and perhaps thousands, of women who worked, as she herself suggested in 2013, across “ethnic and cultural lines to collaborate for the “’greater good.’”

Tennessee Women is a treasure and a wonderful source for those interested in any aspect of the history of this state. While some readers will favor a particular essay or two, and others will read the volume as a monograph, from beginning to end, all will close the book’s covers with a greater appreciation of the efforts and contributions, to home and community, made by Tennessee women.

Brenda Jackson-Abernathy chairs the history department at Belmont University in Nashville. She has published widely on U.S. history during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including Jacksonian America and the Civil War.