Word & Revelation

Poet Terrance Hayes minds and mines language in a pair of new books

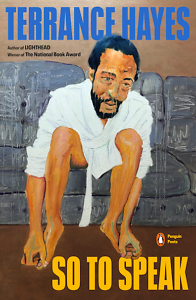

Long established as a lyrical virtuoso with Lighthead (2010), How to Be Drawn (2015), and American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin (2018), Terrance Hayes returns with a bold and effusive collection, So to Speak.

The title comes from a Toni Morrison passage, found in the opening chapter of her nonfiction work Playing in the Dark: “I want to draw a map, so to speak, of a critical geography and use that map to open as much space for discovery, intellectual adventure, and close exploration….” This passage provides more than titular inspiration; it also functions as the creative credo for the collection. Hayes plays with language in a way that is sometimes sweetly irreverent, and at other times, Frankensteinian: “Each new pair of glasses assures things / never look the same, but several glasses /of liquor can create the same feeling. / Balance the morass & the molasses of jackasses.”

Hayes writes with an assumption of Black dignity, which is a certain genre of protest. In a poem titled “An Extended Public Service Announcement,” he writes: “The room may have been built according / To the architecture of farmers and teachers / Dressed as slaves.” Hayes protests the historical assumption that they were mere slaves, by leading with their intellectual capacity. They were dressed as slaves.

Hayes writes with an assumption of Black dignity, which is a certain genre of protest. In a poem titled “An Extended Public Service Announcement,” he writes: “The room may have been built according / To the architecture of farmers and teachers / Dressed as slaves.” Hayes protests the historical assumption that they were mere slaves, by leading with their intellectual capacity. They were dressed as slaves.

So to Speak is divided into three parts: “Watch Your Mouth,” “Watch Your Step: The Kafka Virus,” and “Watch Your Head.” There is a fourth in this group, but it arrives in a different form. Hayes’ simultaneous nonfiction release is called Watch Your Language: Visual and Literary Reflections on a Century of American Poetry, which functions as an overarching commentary on prose and poetry. Its title adds new meaning to the sections of the poetry collection, as if to say, it is all language: “mouth” is language, “step” or movement is language, and of course “head” or thought is language. “Head” could even be said to refer to head gestures, which are a whole genre of language.

In Watch Your Language Hayes begins by making clear the symbiotic relationship of reading and writing: “Such judgements don’t matter when the act of reading is, like the act of writing, mostly a matter of keeping an eye on your thinking, of bearing witness, of keeping record.” He then traces his own genealogy of poets, taking care to offer both examination and elegy. He titles each of the nine major sections of the book as “Twentieth Century Examination,” followed by a question. This format emerges as Hayes’ response to the classic anthology Twentieth Century Poetry by Christopher MacGowan — a collection Hayes indicts for its omission of several Black poets. Each section then begins with a timeline of 20th-century world and literary events and a series of exam questions that befit an academic, yet accessible course on poetry. For instance, he notes on the timeline that W.E.B Du Bois publishes his major work in 1903, and then asks: “What happens if W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk is considered the first hybrid poetry collection?” In another instance, he marks World War I and inquires: “Is what makes a hero heroic what makes a poet poetic?”

In Watch Your Language Hayes begins by making clear the symbiotic relationship of reading and writing: “Such judgements don’t matter when the act of reading is, like the act of writing, mostly a matter of keeping an eye on your thinking, of bearing witness, of keeping record.” He then traces his own genealogy of poets, taking care to offer both examination and elegy. He titles each of the nine major sections of the book as “Twentieth Century Examination,” followed by a question. This format emerges as Hayes’ response to the classic anthology Twentieth Century Poetry by Christopher MacGowan — a collection Hayes indicts for its omission of several Black poets. Each section then begins with a timeline of 20th-century world and literary events and a series of exam questions that befit an academic, yet accessible course on poetry. For instance, he notes on the timeline that W.E.B Du Bois publishes his major work in 1903, and then asks: “What happens if W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk is considered the first hybrid poetry collection?” In another instance, he marks World War I and inquires: “Is what makes a hero heroic what makes a poet poetic?”

The exam questions lead into various elegies and profiles. Notable among these is “My Gwendolyn Brooks,” dedicated to poet Toi Derricotte, in which he chronicles Brooks’ arrival to the poetry scene as a child prodigy. He highlights her literary accomplishments, while identifying the scores of poets who have been influenced and supported by her:

Brooks would be essential to the American literary canon even if all she did was publish A Street in Bronzeville in 1945. She would be essential to the American literary canon even if all she did was get Etheridge Knight writing poems in prison. Even if all she did was pay out of her own pocket to get Audre Lorde’s second book published. Gwendolyn Brooks would be essential even if all she did was influence the ways we think about Blackness.

There is another way to mind language, which Hayes identifies as art: “Drawing, which, for me, is close to the act of writing, is also a way to watch your language.” The author fleshes out this idea with images like his hand-drawn Notes for an Essay on Wallace Stevens and the Audacity of Imagination. These “notes” take the shape of a triangle, arrows, and some text to indicate the locomotion of ideas and language. In each of his profiles, too, he begins with a drawing of the poet-hero.

The relationship of So to Speak and Watch Your Language is that of word and revelation. Hayes’ poetry is a word of mystery. His prose reveals and demystifies the mechanics behind his art. When read together, these works create a twofold experience that fosters an expansion of language — in mind and mouth.

***

So to Speak

By Terrance Hayes

Penguin Books

112 pages

$20

Watch Your Language

By Terrance Hayes

Penguin Books

240 pages

$20

Kashif Andrew Graham is a writer and theological librarian, who received the Humanities Tennessee Fellowship in Criticism for 2023. He enjoys writing poetry on his collection of vintage typewriters and is currently at work on a novel about an interracial gay couple living in East Tennessee.