Write Like I’m Hungry

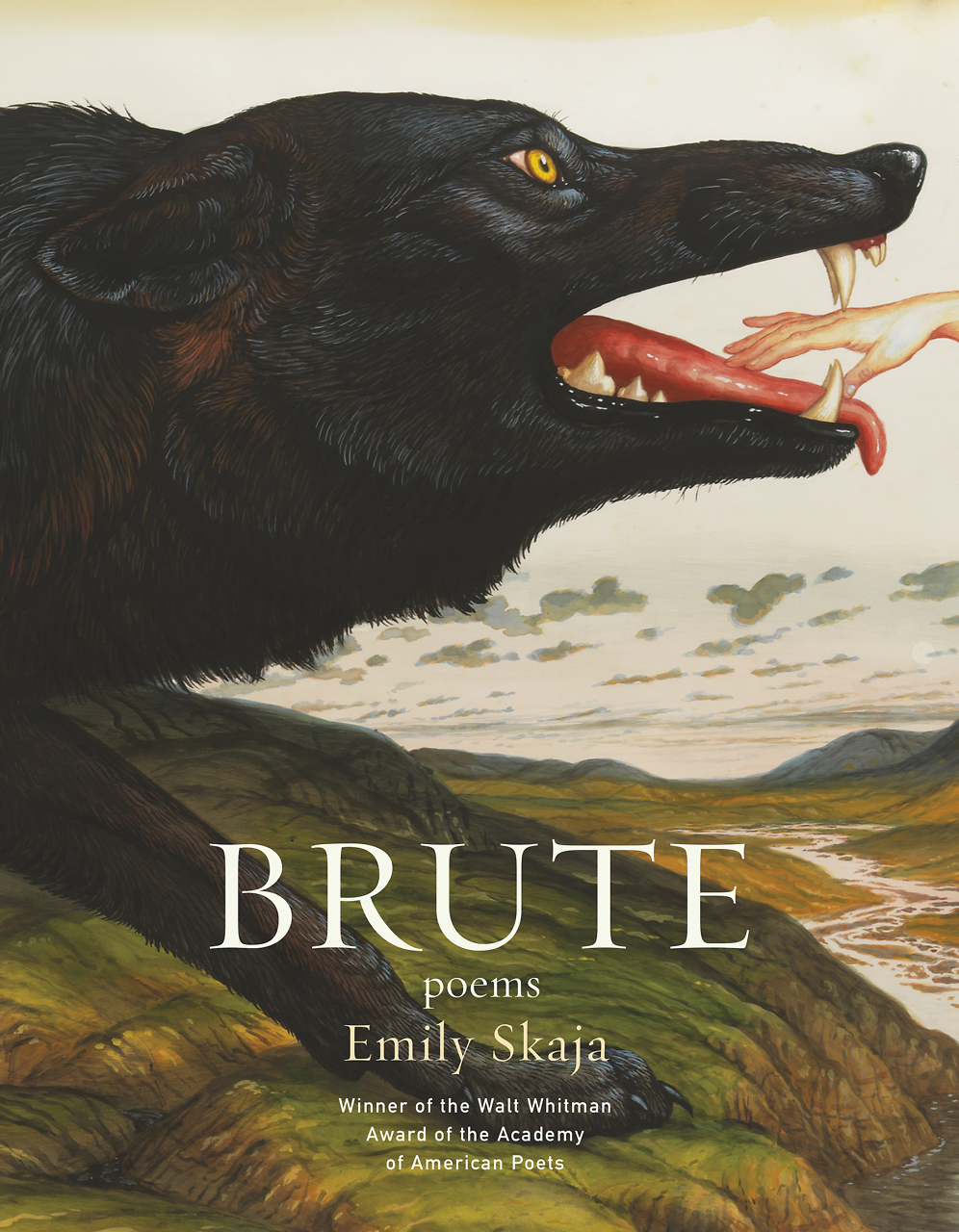

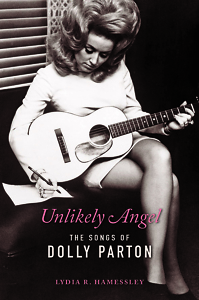

Unlikely Angel delves into Dolly Parton’s formidable skill as a songwriter

In recent years, Dolly Parton seems to have appeared in headlines or trending topic lists practically every day — for a myriad of reasons. Perhaps she’s brought Stephen Colbert to tears with her rendition of a traditional folk ballad. Or her philanthropic efforts are yielding a COVID-19 vaccine. Or she’s voicing support for Black Lives Matter. Or she’s addressing those rumors that her arms are covered with tattoos.

With Unlikely Angel: The Songs of Dolly Parton, musicologist Lydia Hamessley wants to return focus to Parton’s formidable skill as a songwriter. Hamessley argues persuasively that even after decades of prolific composition, resulting in dozens of studio albums and hundreds of recorded original songs, Parton has never received the public recognition that she deserves for her accomplished body of work.

With Unlikely Angel: The Songs of Dolly Parton, musicologist Lydia Hamessley wants to return focus to Parton’s formidable skill as a songwriter. Hamessley argues persuasively that even after decades of prolific composition, resulting in dozens of studio albums and hundreds of recorded original songs, Parton has never received the public recognition that she deserves for her accomplished body of work.

A scholar specializing in Southern Appalachian music and a clawhammer banjo player, Hamessley brings broad knowledge to her discussion of Parton’s songs. While Parton’s methods may be “instinctive and emotional, not theoretical,” Hamessley believes that “musical analysis identifies and clarifies her intuitive musical choices.” In spite of her emphasis on the technical aspects of Parton’s compositions, Hamessley’s analysis remains accessible even to those unschooled in music theory. She draws on extensive research, including her own interviews, and as a result, the book is also filled with Parton’s own comments on her songs, creative process, and career.

Hamessley groups Parton’s songs into “families of tunes,” or categories of subject matter and influence, rather than a chronological survey. “Dolly’s musical work is variegated and folds back on itself,” Hamessley argues, “with all the melodic, harmonic, textual, and thematic overlaps that image brings.” Fittingly, some songs appear in several chapters, reflecting their richness and complexity.

Unlikely Angel presents an inspiring picture of Parton’s creative process as “a mixture of compulsion, ecstasy, and craft.” Already writing music and experimenting with a variety of instruments as a child, Parton developed an unappeasable drive to create songs. Despite the extreme poverty of her Smoky Mountain upbringing, she knew that her life would be devoted to music.

Hamessley uses Parton’s classic “Coat of Many Colors” as a lens through which to examine her creative approach, especially toward songs that reflect the traumas and the powerful imagery in Parton’s impoverished origins. Despite the wildly changed circumstances of Parton’s adult life, Hamessley writes that her music is “a memory palace — a place to store her memories in lyrics and melodies that evoke people, feelings, places, and events, bringing them to life whenever she sings one of her songs.”

Becoming financially independent after years of struggle, Parton also attained creative autonomy. For her, that freedom has meant writing and recording songs that reflect her musical heritage, rather than a mainstream country radio sound. Parton says, “I can still write from my memories and from the stuff that’s in my body. I can still write like I’m hungry, because I am hungry — hungry for the true thing that comes from me as a writer and a singer.”

Becoming financially independent after years of struggle, Parton also attained creative autonomy. For her, that freedom has meant writing and recording songs that reflect her musical heritage, rather than a mainstream country radio sound. Parton says, “I can still write from my memories and from the stuff that’s in my body. I can still write like I’m hungry, because I am hungry — hungry for the true thing that comes from me as a writer and a singer.”

Hamessley devotes two detailed chapters to the influence of Appalachian traditions on Parton’s songwriting and vocal performance. Extensive discussion of Parton’s love for mountain ballad forms and bluegrass structures culminate in a brilliant analysis of Parton’s 1999 pivotal album, “The Grass Is Blue.”

Further chapters feature Parton’s many songs about love and about the particular struggles of women’s lives. From Parton’s fraught association with early mentor and boss Porter Wagoner (resulting in the perennial hit “I Will Always Love You”) to her desire to amplify the daily lives of countless working women (“9 to 5”), Hamessley emphasizes the interplay between vulnerability and strength embodied in Parton’s songwriting.

The closing chapters of Unlikely Angel highlight “Songs of Tragedy” and “Songs of Inspiration.” These subjects reveal the full range of Parton’s creative vision. She breaks hearts with an abandoned orphan’s story in “Me and Little Andy.” She seeks spiritual consolation with “The Seeker.” She experiences a “fusion of the sacred and the erotic” in cathartic live performances. Through these diverse modes, Parton’s work “embodies incongruous images that remind us of our own complex identities.” Her songs have the power to “capture and balance seemingly paradoxical emotional states.”

Unlikely Angel makes an ideal companion to two recent books: Sarah Smarsh’s wonderful meditation on Parton as an emblem of “organic feminism,” She Come by It Natural, and Parton’s own release (co-written with journalist Robert K. Oermann), Songteller, in which Parton provides commentary and anecdotes alongside her song lyrics.

What Hamessley adds to the current Dolly Parton cultural boom is a page-turning deep dive into Parton’s artistry, borne out in her choices as a composer and performer. Unlikely Angel insists on her complexity and seriousness as a songwriter, celebrating an indelible body of work.

Emily Choate is the fiction editor of Peauxdunque Review and holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Mississippi Review, Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Atticus Review, Tupelo Quarterly, Bayou Magazine Online, Late Night Library, and elsewhere. She lives near Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.