Writing

Multiple unpublished novels notwithstanding, I am a writer

I am a writer.

Okay, that’s not the whole story. If someone asked me “What do you do?” as is customary upon first meeting, I would answer “I’m a geologist.” Which, of course, is also incomplete because no one is only their profession. I could just as easily reply that I am a husband, a father, an American, a reader — or that I am just trying to hold it together until the next election is over.

Still, I think “writer” pretty well describes me. An outsider would correctly note that I don’t earn enough money being a writer to claim it as a profession. My lifetime earnings from published short stories, book reviews, and essays would total in the low single thousands, at most. Enough to have paid for a couple of vacations or, entered into another bookkeeping column, some camera equipment used to chronicle those vacations (add traveler and photographer to that list of “I ams”). But as a geologist I am also a writer. Being a successful scientist means communicating effectively, and although I may not be a better scientist than many of my peers, I am a better writer than most. I have made a decent living by competently preparing a variety of reports, plans, and commentaries for a wide range of clients.

So, multiple unpublished novels notwithstanding, I will stick with the first sentence of this essay. (Any interested literary agents may contact me through this publication’s website.)

The origin of my writing desire is obscure. There was no childhood epiphany, no early need to express myself through the written word, no family influence to credit or blame. The writing bug didn’t so much bite as burrow, so that by the time I finished graduate school it had tunneled into my mind. My first short story, other than maybe a long-forgotten school assignment, was a sci-fi, O. Henry-esque tale thrown together during a couple of lunch hours at my first geologist job. Within three years I was taking community college creative writing courses and working on the first of those unpublished novels. (For you agents, that address is Contact Us | Chapter 16.

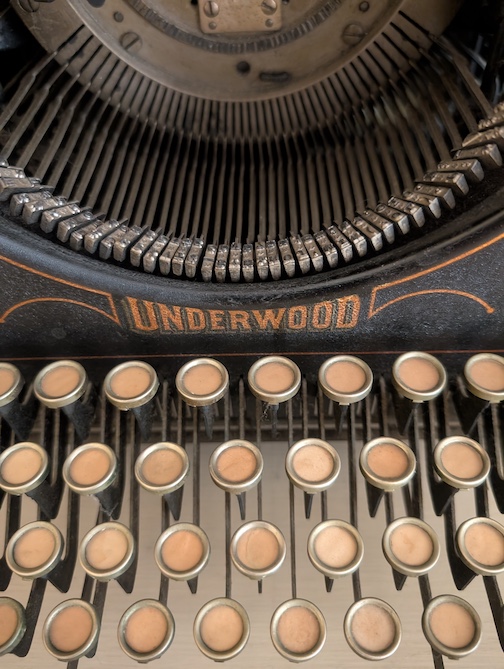

Along the way I developed some writing habits that continue to serve me well. For creative writing, I do first drafts in longhand, pen or pencil on paper. (Technical works are usually composed directly on the computer from handwritten notes.) In the afterword to his novel Dreamcatcher, Stephen King stated that writing the manuscript longhand (with a fountain pen, no less) “put me in touch with the language as I haven’t been in years.” It’s a method that forces focus, a slowing of the creative process that allows le mot juste to be discovered along the way. The second and following drafts can be pounded out on the keyboard, where changes are easier.

I’ve also found that the touch of a good pen or pencil on decent quality paper enhances the creative process. Somehow, those ink and graphite lines look more like art created by a human than do a collection of electrons on a screen. Woodworkers speak in almost religious terms about the pleasure of joining pieces of dead trees by hand; why not the joy of feeling a Blackwing 602 lay down a well-constructed paragraph?

Quite aside from the mechanics, however, is the creative spark of writing. Why do it at all and, once the desire is felt, what inspires the stories and the sentences, paragraphs, similes, and dialogue of which they are constructed? It is the fundamental question of art.

And I have no answer. Seriously. If I did, perhaps those novels would have been published by now. I do know that as I’ve lived my life and developed as a writer, I have accumulated stuff that might push the process along. Physical stuff of the sort George Carlin riffed on when he said that a house is just a place where we keep our stuff. Some of my favorite stuff, writing-related and potentially inspirational, has found its way to my workplace, where I feel closest to my muse.

The foremost thing is the desk itself, a small kneehole built in the early 20th century by the Skandia Furniture Company of Rockford, Illinois. I acquired it long ago in an antique shop in Detroit, then refinished its mahogany veneer top. It’s been with me ever since. Its surface glows in rich browns in the light of my green-shaded desk lamp, the perfect foundation for everything that happens on it.

Sitting on a wooden letterbox to my left is a pencil, not used for writing, on which is printed “What Would Ernest Hemingway Write?” Although he may not have been the best example of a person, no one can argue with his prose. His simple sentences powerfully bring his ideas to life.

My wife’s picture is also readily accessible to the left. Not just any picture, but the first I ever took of her. It was on a cold December night at a long-ago party where I fell in love. She is still the reader I most want to please.

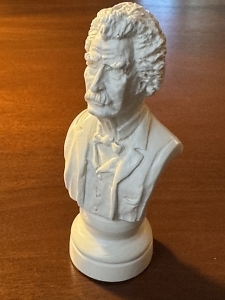

Next to a little brass-and-black clock given to me by my father is a 4-inch-high bust of Twain. No need for a first name, is there? The inventor of modern American literature, he is the author I revisit most often, whose humor and skill leave me in awe.

Skipping to the center-right of the desk I see pens. A cheap ballpoint sits business end down at a jaunty angle on a polished slab of agate. It symbolizes the merging of my science and my art. Next to that is a clear glass pen holder on which rest three of my best pens, gifts from the beautiful brunette in the picture. I use them all, the choice dictated by the mood of the moment.

Leaning against the glass pen holder is a gray rubber rectangle, an eraser printed with humorous intent, “Out damned spot!” from Macbeth, Act V. I purchased it at Shakespeare’s birthplace and have never used it. It is a symbol, not a tool.

Another English author, Arthur Conan Doyle, is represented by a gift from my youngest child: a soy candle smelling of cherrywood, tobacco, and rain titled “Sherlock’s Study.” I love the Holmes stories and the near-mystical atmosphere of their settings.

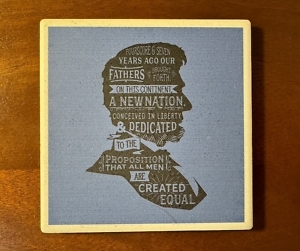

Finally, at my right elbow is a ceramic coaster, ready to hold a glass of whatever beverage of the moment. Obtained in Springfield, Illinois, it features Abraham Lincoln’s profile on a conservative blue background. Inside his profile are the opening 29 words of the Gettysburg Address. If anyone could inspire with language, it was Abe.

And that’s the inventory of my writing landscape, the place to which I am continually drawn, for better or worse. Is this miscellany of stuff inspiration for creativity, prompts for the imagination? Possibly, possibly not. But even if they don’t directly inspire me, I believe they are in the mix, somehow fueling that strange process.

It is a complicated thing, this one percent inspiration of the invention, as Thomas Edison described it. I suspect the brain cooks up story ideas in much the way it builds dreams, as amalgams of past events, desires, and fears, the combined sensory experience that is life on this planet. Mix all of that with an ego large enough to believe you can write something others would want to read and perhaps a little greed for monetary gain, and you have the seeds of creation.

In my case I began as a reader, a lover of a good story. I decided I wanted to become one of “those people” who entertained and enlightened, drawing in others without the need for close personal contact. Just those beautiful pictures painted with words. It seemed to me as good, maybe even better, a profession than the one I had picked in college. Remuneration was certainly a factor, for I began writing when I was poor and had no desire to remain so. Now I am old and beyond the likelihood of fame and fortune.

Yet still I write, unable to explain how or why. All I know is that every time I complete a novel, story, or essay and think “Well, that’s the end of it,” I come back around with another idea, more desire to create. I sit down, favorite writing instrument in hand, good paper flat on that old desk, eyes roaming the mementos arranged before me. Then the mechanics and the spark merge in their mysterious way and I begin.

Copyright © 2024 by Chris Scott. All rights reserved. A Michigan native, Chris Scott is an unrepentant Yankee who arrived in Nashville more than 30 years ago and has gradually adapted to Southern ways. He is a geologist by profession and an historian by avocation.