Writing the Body

Award-winning poet Beth Bachmann discusses her work—and the way her sister’s violent death affects it

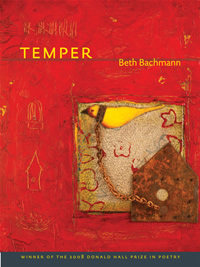

Beth Bachmann’s first volume of poems, Temper, is slim, and the poems themselves are rarely more than a dozen lines long, but there is nothing slight about Bachmann’s work. The poems tell the story of the murder of a young woman, using language that is spare, almost clinical, yet exquisitely crafted. Bachmann’s refined style makes her unflinching depiction of the crime more poignant than gruesome. A story that could be merely lurid becomes tragic when conveyed in images that are both graphic and graceful, as in “Colorization”:

A broken crow drops from the jaw of some animal into the snow.

If we were to encounter it, with our chins tucked to our chests to block the

blizzard,

we might think of it as shadow, but, in truth, the body is red.

There are two ways to define this: restoration and desecration.

It comes down to a question of actuality and intent.

Asked to comment on the inspiration for the poems, Bachmann explained that, while they are rooted in her personal history, they are more than simple autobiography. “Temper is, in many ways, about the unsolved murder of my sister and the impact of that fact,” she said. “The poems are about the unknowable, the inability to assign a single name to the act of violence, and how the lyric form engages in this naming.”

The craft and power of Bachmann’s poetry have not gone unrecognized. Temper won the 2008 Donald Hall Prize in Poetry from the Association of Writers and Writing Programs. Bachmann, who teaches creative writing at Vanderbilt University, will also receive the Kate Tufts Discovery Award, a major prize given annually to recognize “a first book by a poet of genuine promise.” Bachmann answered questions from Chapter 16 in anticipation of the award ceremony in Pasadena on April 28.

The craft and power of Bachmann’s poetry have not gone unrecognized. Temper won the 2008 Donald Hall Prize in Poetry from the Association of Writers and Writing Programs. Bachmann, who teaches creative writing at Vanderbilt University, will also receive the Kate Tufts Discovery Award, a major prize given annually to recognize “a first book by a poet of genuine promise.” Bachmann answered questions from Chapter 16 in anticipation of the award ceremony in Pasadena on April 28.

Chapter 16: Can you remember the first poem that ever moved you?

Bachmann: Gwendolyn Brooks’s “We Real Cool.” I love short form, and in the Brooks poem, there’s so much going on in so little space. Every word attracts.

Chapter 16: When did you start writing poetry?

Bachmann: I took a workshop in college [at Loyola University in Baltimore] with poet Karen Fish. Karen was amazing. She gave me a massive reading list that held a glass up to a place I didn’t know existed, in me and beyond me.

Chapter 16: How do you approach form in your poems? Is it instinctive, or do you deliberately choose it?

Bachmann: Form is so crucial. I think of it again as glass: blown animals, a body to breathe into, heat and shaping. I guess breath can be both instinctive and controlled.

Chapter 16: The poems in Temper are very short; in some cases they almost seem like fragments. You said in an interview last year that your new work is longer. What’s the driving force behind that change?

Bachmann: The new work is only longer by a fraction, a few lines. It’s not so much getting longer, I think, as getting bigger, in terms of aperture and focus on what’s in the field. I don’t want to write longer works, per se, but I wouldn’t mind letting more light in.

Chapter 16: How detached were you from your own emotions as you wrote about the violence in Temper?

Bachmann: Well, now depth of field has got me thinking about distance. And pulled glass has got me thinking of Marianne Moore. I was rereading “An Octopus” the other day and considering the lines, “… as if no branch could penetrate the cold beyond its company”… not decorum, but restraint; … Relentless accuracy is the nature of this octopus ….

Bachmann: Well, now depth of field has got me thinking about distance. And pulled glass has got me thinking of Marianne Moore. I was rereading “An Octopus” the other day and considering the lines, “… as if no branch could penetrate the cold beyond its company”… not decorum, but restraint; … Relentless accuracy is the nature of this octopus ….

I wanted the violence to be relentless and beyond decorum; it seemed to be the only way to accurately render it. I couldn’t do that without distancing the self, going cold in an effort to remain objective. So, I think again of the lens; this time as in documentary— we learn who’s holding it through what we see.

Chapter 16: There are a lot of images of nature going about its business in Temper, in a way that’s both beautiful and merciless. Sometimes it seems almost redemptive; other times it’s horrifying. How do you grapple with your own relationship to the natural world?

Bachmann: I feel I’m only beginning to know nature and I want to know it more. I like the way it makes me think about power, beauty and power. Beauty is easy to forget. I think of Tennessee in summer, how the extreme heat slows, how the thick growth creates privacy and boundary.

Chapter 16: I’m struck by how often the body in Temper is described with reference to a text or a book—”brittle as the bracts pressed into a book,” “her body written over in blossom,” etc. Did you consciously think of the corpse as a kind of text when you were writing the poems?

Bachmann: I was conscious, for sure, of how I was writing the body, how the poems have a body, but are not a body. In the first instance, I was thinking about flower pressing, of opening an old book and the old flower falling out, but then the poem becomes rather quickly about pornography, “open/as a photograph of a girl on a glossy page.” So, yes, many of the poems are about how the female body is written and how I’m engaging in that tradition.

Chapter 16: Do you think of these poems as a statement about sexual or domestic violence? How do you feel about the possibility that people will read them in a politicized way?

Bachmann: It seems to me the personal is political, whether we like it or not. It’s hard for me to imagine art about rape that doesn’t make a statement about rape, somehow, but I was aiming to make art, not a statement, though I’m not sure what one is without the other.

To read an excerpt from Temper in Chapter 16, click here.