The Nation’s Oldest Student

Rita Lorraine Hubbard shares the remarkable life of Mary Walker, who learned to read at age 116

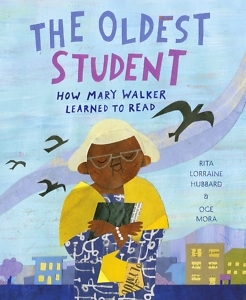

Born into slavery in Alabama in the mid-19th century, Mary Walker was freed at the age of 15, moved to Chattanooga in 1917, and learned to read at the extraordinary age of 116. “You’re never too old to learn,” she famously remarked. Author Rita Lorraine Hubbard brings Mary’s inspiring story to young readers in her new picture book biography, The Oldest Student: How Mary Walker Learned to Read.

Dubbed “the nation’s oldest student” by the U.S. Department of Education, Mary — who lived through 26 presidents, outlived her entire family, and eventually became a Chattanooga icon — “studied the alphabet until her eyes watered” at well past the age of 100. As a former slave, once forbidden to learn reading and writing, she finally met her lifelong goal and proudly read from the Bible given to her as a teen by a woman who had told her, “Your civil rights are in these pages.”

Dubbed “the nation’s oldest student” by the U.S. Department of Education, Mary — who lived through 26 presidents, outlived her entire family, and eventually became a Chattanooga icon — “studied the alphabet until her eyes watered” at well past the age of 100. As a former slave, once forbidden to learn reading and writing, she finally met her lifelong goal and proudly read from the Bible given to her as a teen by a woman who had told her, “Your civil rights are in these pages.”

Hubbard fleshes out Mary’s extraordinary life in this reverent and loving tribute, illustrated in layered, textured collage art by Caldecott Honoree Oge Mora. On the book’s first spread, Hubbard writes that Mary, as an enslaved girl, watched the swallows soar through the sky and wondered: “That must be what it’s like to be free.” Throughout the book, Mora repeatedly pictures these birds in flight, a symbol of Mary’s freedom and her invincible spirit.

Chapter 16 talked to Hubbard via email about the biography, as well as her love of the compelling stories that history tells.

Chapter 16: You live in Chattanooga, a city that, in more ways than one, regularly commemorates Mary Walker’s life. And you’ve written previously about African Americans in your city (African Americans of Chattanooga, published in 2007). While researching this book, was there anything you learned about Mary’s life that surprised you?

Rita Lorraine Hubbard: Yes! I was surprised to learn that Mary had participated in a live interview in the early to late 1960s and that this interview had been recorded on an LP that, unfortunately, has long since disappeared. Thankfully, I received the full transcript and was able to read Mary’s firsthand account of her life. She shared how she was forced to be a blacksmith at a young age and told of how she had sharecropped alongside her second husband for four decades or more.

Another big surprise was that she never mentioned grandchildren in her interview. I knew she had three sons, but there was no mention of wives or children/grandchildren. Mary told the interviewer that, after her eldest son died, she was all alone in the world and had outlived all her relatives. I was unable to determine if her sons had never fathered children, had fathered children who later moved far away, or if they had simply outlived their own life-mates and children.

The biggest surprise of all was discovering what a survivor Mary was.

Chapter 16: Was the research for this story challenging, given that (as you note in the book’s back matter) little is known about her life from her emancipation at age 15 until she learned to read at age 116? And what was it like for you to fill in those gaps yourself?

Chapter 16: Was the research for this story challenging, given that (as you note in the book’s back matter) little is known about her life from her emancipation at age 15 until she learned to read at age 116? And what was it like for you to fill in those gaps yourself?

Hubbard: It was challenging in the beginning. But then I approached Mr. John L. Edwards (son of the founder of The Mary Walker Foundation), who generously gifted me with the full transcript of Mary’s interview. The interviewer asked Mary plenty of questions that could have filled in the gaps in her life story, but Mary was too afraid to answer some of the questions. Even though it was the mid ‘60s and slavery was long past, she was hesitant to speak out because of “the Klux.” She would stumble over her words or (as the interviewer noted) she would look concerned and would simply not answer. As for my “imaginings,” I created the elderly neighbor who offered to accompany Mary to the reading class. I used his offer to convey Mary’s resolve. I imagined that, after years of depending on others to read for her or help her, Mary would have finally been ready to do things for herself.

Chapter 16: You wrote your first picture book (Hammering for Freedom) last year. What was the spark for wanting to write in the picture book form?

Hubbard: I used to blog frequently about writing tips and opportunities, and I encouraged my followers to “put their work out there.” I wrote, “It’s true that you may not win, but you definitely won’t win if you don’t at least try.” Then one day I realized I hadn’t been taking my own advice. I had known about Lee & Low’s New Voices Award competition for years. I had even entered once, but I didn’t win. But in 2012, I decided to throw my hat in the ring once more. I had stumbled across William Lewis’ name — he is the subject of Hammering for Freedom — years earlier, while I was researching African Americans of Chattanooga, so I decided to write about him. And I won first place! That entry, which was initially titled Bill’s Family Reunion, eventually became Hammering for Freedom. Since it was a picture book competition, it was a given that it would be a picture book.

Chapter 16: You regularly write about picture books on your site, Picture Book Depot. Do you feel like reading as many picture books as you do is its own kind of education in writing them?

Hubbard: Yes! I believe that “the well-read writer writes well.” One of the first things I learned when I decided to focus on my writing was that you should read as many books in your chosen genre as you can get your hands on. Since I couldn’t always find the latest picture books at my local library and my budget wouldn’t allow me to purchase all the books I wanted to read, I began reviewing books for a colleague, who owned her own review site. Later, I decided to start a site of my own that was dedicated solely to picture books. Now I get to read all sorts of picture books by a variety of writers with a wide range of amazing writing styles. I get to see how different writers handle different story lines and concepts. But best of all, I get to pass these books along to schools, church libraries, and deserving young children who may not otherwise have an opportunity to own a book.

Chapter 16: What was it like for you to first see Oge Mora’s artwork for your story?

Hubbard: It made me cry. Really. I choked up and cried. It’s an amazing experience to see the words you write come to life on someone’s canvas, especially someone as gifted as Oge. She brought Mary Walker to life. Thank you, Oge.

Chapter 16: Did your love of history — and digging in deep to research it — begin in your childhood?

Hubbard: Yes. As a child, I loved listening to my mother tell what life was like when she was young. I was fascinated with how much things cost — or should I say, how much they didn’t cost? (A few pennies for a loaf of bread. And ten cents got you an all-day movie pass, with cartoons and other serials included. I was fascinated!) I was also intrigued by stories my grandmother told about the games she and her friends played when they were young, the food they ate, and not being allowed into white hospitals. These amazing stories made me want to know more about “yesterday.”

Chapter 16: Are you planning school visits for this book so that you can tell students, “You’re never too old to learn”?

Hubbard: Definitely!

Julie Danielson, co-author of Wild Things! Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature, writes about picture books for Kirkus Reviews, BookPage, and The Horn Book. She lives in Murfreesboro and blogs at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast.