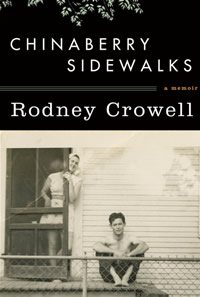

The chinaberry tree is one of those hardy exotics that, like kudzu and Japanese honeysuckle, seems to be able to take root anywhere and needs no coddling to thrive. In Chinaberry Sidewalks: A Memoir, acclaimed singer/songwriter Rodney Crowell—who has penned hits for Emmylou Harris and Bob Seger, among others—transforms it into a fitting symbol of his hardscrabble childhood. Crowell’s account of his impoverished, often violent upbringing is a study in the ways that life and love can survive, even flourish, in the most unlikely circumstances.

Crowell was born in Houston, Texas, in 1950 and grew up in a flimsy, post-World War II tract house that literally crumbled under the “elemental onslaught of southeast Texas weather” and the ordinary dings inflicted by neighborhood kids at play. “On a clear night,” writes Crowell, “stars could be seen twinkling through the holes in the roof.” Rain and swarms of mosquitoes poured in on the family, and an army of cockroaches made itself at home in the kitchen. The vermin were undeterred by extravagant use of insecticides, including DDT, which was spewed out by the “Mosquito Dope Truck”—a mechanical Pied Piper that Crowell and his playmates joyfully followed through the streets, inhaling “great lungfuls of the toxic blue smoke.”

Crowell devotes a considerable number of pages in Chinaberry Sidewalks to describing the decrepit, tainted environment of his boyhood, with language so vivid readers are apt to start feeling a little stifled and itchy. It’s a masterful bit of stage-setting for the real focus of his story: a family that was, in many ways, as dysfunctional and dangerous as the world around them. J.W. and Cauzette Crowell were a pair of thwarted dreamers who took comfort in alcohol and religion, respectively. They vented their disappointment and frustration through fierce quarrels, physical fights, and harsh discipline of their only child—the latter usually inflicted with switches from the chinaberry trees that graced the yard of their tumbledown house.

Crowell devotes a considerable number of pages in Chinaberry Sidewalks to describing the decrepit, tainted environment of his boyhood, with language so vivid readers are apt to start feeling a little stifled and itchy. It’s a masterful bit of stage-setting for the real focus of his story: a family that was, in many ways, as dysfunctional and dangerous as the world around them. J.W. and Cauzette Crowell were a pair of thwarted dreamers who took comfort in alcohol and religion, respectively. They vented their disappointment and frustration through fierce quarrels, physical fights, and harsh discipline of their only child—the latter usually inflicted with switches from the chinaberry trees that graced the yard of their tumbledown house.

Crowell’s depiction of his parents and their kin is as unsparing as his description of the family’s sorry dwelling. Riled up for one of their vicious fights, J.W. and Cauzette were “eight-year-olds in drunken, thirty-something bodies powered by pent-up rage.” J.W. regularly knocked Cauzette around, once going so far as to break her arm. He drank hard and dallied with other women. Cauzette got in a few licks of her own, but mostly confined herself to verbal jabs. Her violence was visited primarily on her son. She was a “left-handed Zorro” with a switch, Crowell writes, and “To whip the daylights out of me and leave it at that was something she simply couldn’t do. Until the markings on my legs and butt were examined and pronounced of a quality in keeping with her high standards, the tanning of my hide was never considered complete.”

As for the extended family, it included grandmother Iola, who “meditated and honed on the craft of farting, always striving for greater heights in artistic expression” and great-grandfather Lyin’ Jim, whose “sexual preferences included daughters, sisters, granddaughters, neighbors’ wives, and the odd farm animal.” According to Chinaberry Sidewalks, almost everyone in young Rodney’s world was inclined to filthy personal habits and liberal use of profanity. No one could accuse Crowell of writing a polite memoir.

Even so, the book is not in any way an exercise in anger or self-pity. On the contrary, it’s Crowell’s heartfelt, unsentimental love letter to his parents, whom he not only loves but admires. He writes with great sympathy about both the senior Crowells, who had youthful dreams that were crushed by poverty and bad luck. Cauzette desperately wanted an education but was kept at home on her family’s sharecrop farm. J.W., also denied the formal education he wanted, longed for a career as a singer and musician. He had to make do with occasional gigs in Houston honky-tonks and with teaching his young son to love the music of Hank Williams, Jimmie Rodgers, and the rest of the country-music pantheon. One of the loveliest passages in the book recounts the time J.W. took Rodney—then just a toddler—to see one of Williams’ last performances. Hoisted on his father’s shoulders, Crowell experienced the music as a revelation, and the memory provided him with a key to understanding J.W. “Hank Williams was what my father wanted to be—a Grand Ole Opry star,” writes Crowell. “Taking me to see him perform was his way of saying, Look at me up there on that stage, son, that’s who I really am.”

Even so, the book is not in any way an exercise in anger or self-pity. On the contrary, it’s Crowell’s heartfelt, unsentimental love letter to his parents, whom he not only loves but admires. He writes with great sympathy about both the senior Crowells, who had youthful dreams that were crushed by poverty and bad luck. Cauzette desperately wanted an education but was kept at home on her family’s sharecrop farm. J.W., also denied the formal education he wanted, longed for a career as a singer and musician. He had to make do with occasional gigs in Houston honky-tonks and with teaching his young son to love the music of Hank Williams, Jimmie Rodgers, and the rest of the country-music pantheon. One of the loveliest passages in the book recounts the time J.W. took Rodney—then just a toddler—to see one of Williams’ last performances. Hoisted on his father’s shoulders, Crowell experienced the music as a revelation, and the memory provided him with a key to understanding J.W. “Hank Williams was what my father wanted to be—a Grand Ole Opry star,” writes Crowell. “Taking me to see him perform was his way of saying, Look at me up there on that stage, son, that’s who I really am.”

Crowell, of course, went on to fulfill his father’s dreams and then some, becoming a highly successful songwriter, performer, and producer, as well as a member of one of country music’s royal families through his marriage to Rosanne Cash. (The marriage produced three children and ended in divorce in 1992.) Readers who come to Chinaberry Sidewalks looking for an insider’s account of the music business or for celebrity tidbits, however, will be disappointed. The book contains very little about Crowell’s career, except insofar as it made it possible for him to care for his parents and provide them with the chance to meet some of their idols. Crowell devotes a lengthy epilogue to an account of their last days, which, largely thanks to their son, were happier than any they had known during those early years in Houston.

In spite of the touching sweetness of the epilogue, Chinaberry Sidewalks is not a pretty story. Crowell tells it with humor and grace, but also with real immediacy and power. The book reads like a well-wrought novel, with brilliantly rendered detail and with characters who are complex and contradictory—in short, fully human. Chinaberry Sidewalks is everything a memoir ought to be and will leave readers hoping that Crowell has another book or two in him.

Rodney Crowell will talk about Chinaberry Sidewalks: A Memoir at a taping of “A Guitar and a Pen Old Time Radio hour with Robert Hicks” on May 26 at 6 p.m. The taping takes place at Puckett’s Grocery and Restaurant in Franklin. Tickets are $15 and reservations can be made by calling 615-794-5527.

Tagged: Nonfiction