Report from Chattanooga, Day Three

Sadness and laughter punctuated the final day of the Conference on Southern Literature

April 19, 2011 John Shelton Reed opened his remarks Friday evening by asking for a moment of silence for the members of the Fellowship who have died since the last meeting in 2009: Henry William Hoffman, Barry Hannah, Romulus Linney, and Reynolds Price. There was a genuine sadness in the room as he read each name, but the somber mood didn’t last long once Reed turned to the task of introducing Dorothy Allison, the keynote speaker. He got a laugh when he remarked on “how funny Dorothy can be, if sometimes in a disturbing sort of way.” Allison lived up to that intro with a speech that was indeed funny, disturbing, and quite moving. Citing her “working-class tendency to over-prepare,” she said she’d actually written three speeches for the occasion and would try to meld them together—which she then proceeded to do brilliantly, in a piece of performance art that transcended any notion of an ordinary keynote speech. It’s impossible to describe it here in a way that would do it justice, but you can see a video of the whole event at Chattarati. After Allison’s speech, a small crowd braved the pouring rain to visit Tanner-Hill Gallery for a reception featuring paintings by Louis Rubin and Clyde Edgerton. Jayne Anne Phillips, Elizabeth Spencer, and Madison Smartt Bell were just a few of the writers who were there.

April 19, 2011 John Shelton Reed opened his remarks Friday evening by asking for a moment of silence for the members of the Fellowship who have died since the last meeting in 2009: Henry William Hoffman, Barry Hannah, Romulus Linney, and Reynolds Price. There was a genuine sadness in the room as he read each name, but the somber mood didn’t last long once Reed turned to the task of introducing Dorothy Allison, the keynote speaker. He got a laugh when he remarked on “how funny Dorothy can be, if sometimes in a disturbing sort of way.” Allison lived up to that intro with a speech that was indeed funny, disturbing, and quite moving. Citing her “working-class tendency to over-prepare,” she said she’d actually written three speeches for the occasion and would try to meld them together—which she then proceeded to do brilliantly, in a piece of performance art that transcended any notion of an ordinary keynote speech. It’s impossible to describe it here in a way that would do it justice, but you can see a video of the whole event at Chattarati. After Allison’s speech, a small crowd braved the pouring rain to visit Tanner-Hill Gallery for a reception featuring paintings by Louis Rubin and Clyde Edgerton. Jayne Anne Phillips, Elizabeth Spencer, and Madison Smartt Bell were just a few of the writers who were there.

Saturday morning—the weather blessedly clear and cool after Friday’s steady rain—Bell joined Richard Bausch and Robert Morgan for a panel discussion on “The Ultimate Conflict—Writing about War.” Morgan spoke first, noting Americans’ “fuzzy sense of the past” and saying that war writing should be grounded in a historical context. “A culture is defined by the wars it has fought, or not fought,” he said. Bell addressed the question of our fascination with war and with violence generally, citing the famous quote attributed to Robert E. Lee: “It is well that war is so terrible, else we’d come to love it too much.” He talked about his belief that violence, for all its horror, arises from a need for catharsis, and he spoke of people who seem to have a genuine gift for fighting. Later in the discussion, Morgan echoed Bell’s point, saying, “Basically, all of us love war. It’s a part of our instincts, and it’s important to remember that.” Bausch argued that the warrior mentality is conditioned, and illustrated his point by describing his own transformation during Air Force basic training in the mid-60s. He spoke of realizing that “I had been made over by the experience,” and described the process as “savvy and wicked.”

Saturday morning—the weather blessedly clear and cool after Friday’s steady rain—Bell joined Richard Bausch and Robert Morgan for a panel discussion on “The Ultimate Conflict—Writing about War.” Morgan spoke first, noting Americans’ “fuzzy sense of the past” and saying that war writing should be grounded in a historical context. “A culture is defined by the wars it has fought, or not fought,” he said. Bell addressed the question of our fascination with war and with violence generally, citing the famous quote attributed to Robert E. Lee: “It is well that war is so terrible, else we’d come to love it too much.” He talked about his belief that violence, for all its horror, arises from a need for catharsis, and he spoke of people who seem to have a genuine gift for fighting. Later in the discussion, Morgan echoed Bell’s point, saying, “Basically, all of us love war. It’s a part of our instincts, and it’s important to remember that.” Bausch argued that the warrior mentality is conditioned, and illustrated his point by describing his own transformation during Air Force basic training in the mid-60s. He spoke of realizing that “I had been made over by the experience,” and described the process as “savvy and wicked.”

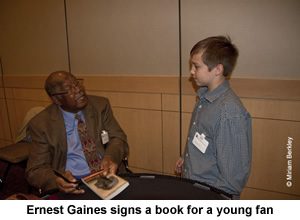

Midday we all boarded school buses for a trip to the Chattanooga Convention Center for a luncheon and a speech from Roy Blount Jr. Before Blount took the podium, Wendell Berry presented the Cleanth Brooks Medal for Lifetime Achievement to Ernest J. Gaines (author of The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman and A Lesson Before Dying.) Berry and Gaines have been friends since their student days, more than fifty years ago, and the sense of continuity—and, yes, fellowship—as Gaines spoke was powerful. Blount, of course, lightened things up considerably, talking about the oddities of Southern culture and the need to explain pig tossing, infant baptism, and the Rapture to his neighbors in Massachusetts. He took questions from the audience and wrapped up by reading “The Way Folks Were Meant to Eat”—a hilarious piece, and a nice bit of enabling for those of us who were scarfing down a second dessert.

Several awards were given at the Tivoli during the course of the day, including the Robert Penn Warren Award for Fiction, which Jill McCorkle presented to Chattanooga native Elizabeth Cox. Jerre Dye, a young playwright from Memphis, received the Bryan Family Foundation Award for Drama and performed two great monologues, including an awesome screed against air conditioning that would make anybody think twice about turning down the thermostat.

Several awards were given at the Tivoli during the course of the day, including the Robert Penn Warren Award for Fiction, which Jill McCorkle presented to Chattanooga native Elizabeth Cox. Jerre Dye, a young playwright from Memphis, received the Bryan Family Foundation Award for Drama and performed two great monologues, including an awesome screed against air conditioning that would make anybody think twice about turning down the thermostat.

Dye took part in a fascinating panel on “Producing Plays” with Jim Grimsley and Katori Hall. A lot of the discussion centered on the difficulty of getting plays staged if they contain anything controversial, and about the burden of dealing with the New York-centered theater culture. “I’m tired of everybody having to move to New York to be a playwright,” said Hall. Grimsley spoke about the burden of nostalgia that afflicts Southern literature, and said, “I don’t want to be Faulkner, unable to overcome the past. I want to overcome the past.”

Sam Pickering and Clyde Edgerton had a sharp-edged and funny conversation about “Southern Politics and Southern Literature.” Pickering, with his characteristic wit, went after gun fetishism and right-wing prudery, while Edgerton took a more thoughtful stance, arguing that the divisive political culture is “convenient for politicians” and that literature can encourage openness and tolerance.

The final session of the conference had Nashville’s Minton Sparks accepting the Fellowship of Southern Writers Award for the Spoken Word, presented by Dorothy Allison, who decried the deadpan delivery that is SOP for contemporary poets. “I believe they train young poets to read badly,” Allison said, noting that there seems to be a belief that “if you read in a flat, grating monotone, you must be a genius.” Sparks presented a thirty-minute performance of what she calls her “genre-less pursuit” combining poetry, music, and dramatic monologue.

After a few closing words from Allen Wier, the conference was over, though a few folks lingered to get a last book signed or picture taken. It will be two years before this wonderful group of writers and readers gathers again. That seems like a long wait.

Read about the first day of the Conference on Southern Literature here, and about the second day here.

Photos copyright (c) 2011 by Miriam Berkley. Used with permission. All rights reserved.