The Boy's Alright

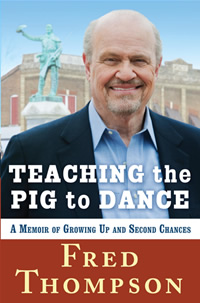

Former Senator Fred Thompson talks with Chapter 16 about his new memoir, Teaching the Pig to Dance

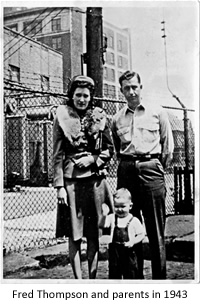

Born in 1942 to a wise-cracking car salesman and a woman who appreciated politically incorrect humor, Fred Dalton Thompson grew up in Lawrenceburg, Tennessee, where his Grandma Thompson padded around town showing off her excised goiter (which she carried around in a handkerchief), where he heard old men swap lies at the Blue Ribbon Café, and where he wandered into his share of boyhood scrapes. He was forced to become a man quickly when, at seventeen, he married his high-school sweetheart Sarah before their son Tony was born. They were together a quarter-century, while Thompson graduated from college, became a Barry Goldwater acolyte, received a scholarship to Vanderbilt law school, was appointed as minority counsel to the Senate Watergate committee, and helped take down Tennessee Gov. Ray Blanton, who was busted in a cash-for-clemency scheme.

Thompson spent eight years (1994-2002) in the U.S. Senate, where, perhaps most notably, he led an investigation into both parties’ campaign finance practices—an effort that Congress predictably capped at one year, rendering it essentially a wasted effort. Since his divorce in 1985, he has also conducted a failed presidential bid and taken roles in a long list of movies and television shows, and he has three more films forthcoming. He currently hosts a Westwood One talk radio program, The Fred Thompson Show, and lives in McLean, Virginia, with his wife Jeri and their young son and daughter.

In his new memoir, Teaching the Pig to Dance, Thompson characterizes his boyhood self as essentially a ne’er-do-well who was lucky to have been born into a family loving and tolerant enough to put up with him. (The shenanigans really aren’t so bad.) “Being really lucky is being born in the United States to good parents,” he writes. “The acorn still doesn’t fall far from the tree. Our parents, the community we grew up in, and our early experiences form the core of our character, affect the decisions that we make and the course of our lives. I know this better than most.” With stories that are homespun and occasionally bawdy, Thompson recalls the lives of characters such as his beloved high school Coach Staggs (“Captain Ahab without the humor”), who shaped his own personal journey.

In his new memoir, Teaching the Pig to Dance, Thompson characterizes his boyhood self as essentially a ne’er-do-well who was lucky to have been born into a family loving and tolerant enough to put up with him. (The shenanigans really aren’t so bad.) “Being really lucky is being born in the United States to good parents,” he writes. “The acorn still doesn’t fall far from the tree. Our parents, the community we grew up in, and our early experiences form the core of our character, affect the decisions that we make and the course of our lives. I know this better than most.” With stories that are homespun and occasionally bawdy, Thompson recalls the lives of characters such as his beloved high school Coach Staggs (“Captain Ahab without the humor”), who shaped his own personal journey.

Chapter 16: You decided to concentrate your memoir on growing up in Lawrenceburg. Happier memories in small-town Tennessee than in the Senate?

Thompson: Well, I first set out to do the obligatory autobiography that everybody in America seems to do. I noticed the president already had, too, and I wanted to try and catch up with him. The first chapter, of course, was going to be growing up in Lawrenceburg, and the second chapter was going to be Watergate. I think I sent them both chapters at the same time. They said, “You know, that first one is a whole lot more interesting than the second one. Could you elaborate on that?” I said, “Well, yeah.” I was trying to hold it down, to be concise, because it was going to be just one chapter. … One thing led to another, and we just decided to go with that. As I got into it, I found that it really was nice—and sentimental and funny and stuff. Instead of going back and trying to dredge up the dry bones of Watergate and the Senate and all that kind of stuff, all of which could have its own book. Besides, I can always do the other some other time.

Chapter 16: Do you think you will?

Thompson: I think probably so. This will probably lead to that. I had a pretty detailed outline for the whole thing, and I’ve still got that. And it would make sense to do it. It’s just that I’m guessing it’s kind of like child birth, and the final stages of it—I sure don’t want to do it again. But I may change my mind about that.

Chapter 16: In writing this book, did you think about other memoirs you’d read and liked as a sort of model or prosaic aspiration?

Thompson: No, I really didn’t. I just don’t know how to put it any other way: My stories were my stories, and I had to decide what to present and what not to present in my own voice. You know, it’s got to be in your own voice if it’s going to work. People who know me or have seen me or whatnot, kind of know my voice, I think. I wanted it to be authentic, I wanted it to be genuine, and I wanted it to appear that way also.

Thompson: No, I really didn’t. I just don’t know how to put it any other way: My stories were my stories, and I had to decide what to present and what not to present in my own voice. You know, it’s got to be in your own voice if it’s going to work. People who know me or have seen me or whatnot, kind of know my voice, I think. I wanted it to be authentic, I wanted it to be genuine, and I wanted it to appear that way also.

It wasn’t a conscious thing as such. I was just quite comfortable in telling it my own way hoping that that would translate. I must say—I mean this sounds awfully presumptuous—but parts of it every once in a while I think of Mark Twain a little bit, maybe Huckleberry Finn and a few things like that. To me, it had a little bit of that feeling in parts of it. But no pattern really.

Chapter 16: You mention being in the campaign bus in South Carolina when it became clear to you that you wouldn’t become president. You’d come in third in that state’s primary, and you describe it was humbling. Were you genuinely surprised?

Thompson: Well, I don’t know how to answer that, really. I don’t think it’s a yes or no. The whole thing is an unfolding, a gradual process. It has a general trajectory, but there are a lot of ups and downs. My own experiences in my Senate campaigns—you have good days and bad days. You can start out way behind and wind up way ahead. The dynamics of a presidential campaign are different. But in a way, there are several different state campaigns.

I was very well aware that many are called and few are chosen. There have been a lot better men than me who didn’t get as far as I did, Howard Baker coming to mind first and foremost. So you know the odds on something like that, but you don’t go in planning on losing, either. I hadn’t been in it that long or done that much, but I’d never lost. So I kind of figured I could beat the system by getting in later.

Chapter 16: And you were golden there for a while …

Thompson: Yeah, I could have won if I’d just stayed out of the race.

Everybody’s forgotten about this, but Joe Lieberman was leading the Democratic pack for president—I can’t even remember the year now—and he never got out of the chute. There have been a lot of examples of that. So I was very aware of that. But I was competing with guys who have been organizing and raising money a lot longer than I had, and it’s a marathon and not a sprint. It’s not a matter of what your national popularity is—I mean, my poll numbers continue to be pretty good on that basis. It’s a matter of how many people come out to a caucus on a winter night in Iowa, or come out in New Hampshire and godforsaken places like that.

Everybody’s forgotten about this, but Joe Lieberman was leading the Democratic pack for president—I can’t even remember the year now—and he never got out of the chute. There have been a lot of examples of that. So I was very aware of that. But I was competing with guys who have been organizing and raising money a lot longer than I had, and it’s a marathon and not a sprint. It’s not a matter of what your national popularity is—I mean, my poll numbers continue to be pretty good on that basis. It’s a matter of how many people come out to a caucus on a winter night in Iowa, or come out in New Hampshire and godforsaken places like that.

Chapter 16: Your book is dedicated to the memory of your daughter Betsy, whose loss has obviously informed your public-policy worldview. Did your bout with cancer offer any such insights?

Thompson: Sure, yeah, it does. It definitely gets your attention from a lot of different standpoints. It reminds you how brief all of our lives are. After you get over the initial shock, you start, in my case, understanding that this is not going to keep you from living a natural life span. As I say in the book, I thought when they started talking about intravenous treatment, “This is chemo.” They hooked me up and gave me a few treatments, and it was nothing. I mean, there were no after-effects. I was not sick ever, not one day, not one minute. I would never have known I had anything if the doctor hadn’t told me.

I have a special antennae for these politicians who demagogue the big drug companies and all that. There’s a cost-benefit analysis you gotta apply to everything in life. But I’m still on the side of developing things that are going to keep a child from dying. … We’ve become too much of a consuming nation, and not an investing nation and not looking to the future enough. So yeah, that brings it right to your doorstep when you’re diagnosed like that.

Chapter 16: It sounds like your dad Fletch was endlessly entertaining, and you obviously had a lot of respect for him.

Thompson: He was the funniest human being I’ve ever known—to the very literal, very last, when he could not speak, and we were rolling him out of the operating room. You know [with pen and paper], he was encouraging me to sue the doctor who’d just operated on him. He never told a joke; he just had a comment or an insight or an observation about things. He saw the comedy, the tragedy, and the irony of life. It’s a certain brand of humor you’ve got to be there to appreciate. Some of it would probably be considered totally politically incorrect, or cruel even. My mother was the brunt of a lot of it, but she has a great sense of humor. She told me that story about the twisted legs just a few months ago for the first time. [Once, at an auction, the auctioneer announced the next item for sale, a piece of furniture with “twisted legs,” at which point Fletch shot up and said, “They’re getting ready to sell my wife!”] We were laughing about that just recently. She still laughs about that stuff. That’s just the way I grew up.

He got it from his mother, who was a character from the word go. That was kind of the atmosphere I breathed down there and grew up with. And I’m sure those around me see more and more of it in me as I get into my dotage.

Chapter 16: Though he was unsuccessful in his bid for Lawrence County sheriff —and, as you write, probably fortunately so—do you think your political instincts follow from him?

Thompson: Well, I don’t think so. The thing I remember about him is his integrity and the things he’d talk about. Looking back on it, he was talking about being sheriff of Lawrence County, he was kind of naïve. People would tell Momma every once in a while, he’s too good a man to be sheriff, and of course that would make everybody mad and stuff, but it was really true. My mother has a streak of skepticism in her, and I take a little bit after her, I think, in that respect. I’m a little bit more realistic. Dad was a soft touch. He was a tough guy, but he was a soft touch.

Chapter 16: You write in the book about coming of age politically in college. Is it fair to say that Barry Goldwater is responsible for your party identity and ideology?

Thompson: No question about it. I found him to be very inspiring as a young man. I liked his straightforwardness, his cantankerousness, I even liked his hopelessness. That was a great thing for an idealistic college kid—battling against the overwhelming odds. As I say in the book, I thought in terms of what I wanted to be rather than what I was, and he offered … freedom, independence and cantankerousness, and all those things that I liked.

Thompson: No question about it. I found him to be very inspiring as a young man. I liked his straightforwardness, his cantankerousness, I even liked his hopelessness. That was a great thing for an idealistic college kid—battling against the overwhelming odds. As I say in the book, I thought in terms of what I wanted to be rather than what I was, and he offered … freedom, independence and cantankerousness, and all those things that I liked.

Chapter 16: I was reading something in The Wall Street Journal about your book …

Thompson: You picked out the only negative review, you rascal. I might have known!

Chapter 16: I was just going to ask if you agree with the assessment that your book is free of moral and political messages.

Thompson: Well, no. I think the reviewer was free of insight. I go back to what [Senator] Sam Ervin said: “If you can paint a picture of a cow, you didn’t need to write on it, ‘This is a cow.'” That’s what I tried to do, but it was not about partisan politics, which I think most people would have expected. The ideas, the virtues that made us the country that we are, and the ones that my folks brought in off the farm, and the kind of things they taught us, and the lessons I learned of accountability and personal responsibility and things of that nature, which underlie kind of everything else. It’s not Democrat/Republican stuff. It’s how you view yourself in the world and how you view your relationship to government. I think I do express some of my values about certain things in relationship to the people I knew. … It’s not designed to preach or beat anybody over the head with a message. That’s what everybody else does. I wanted to do something else.

Chapter 16: So the obligatory question: You’re really done with politics?

Thompson: Yeah, sure am. I’m done with running for office. I’m certainly involved and will continue to be involved, shoot my mouth on the radio without consequences, which is how I like it.

Chapter 16: What’s up with the goatee on the book jacket?

Thompson: You gotta be ingenious to maintain your status as a sex symbol. And I’ve had to make some adjustments along the way. I’ve done a commercial which you’ll probably be seeing ad nauseam, and they wanted me to shave it off. And I’ve got like three movies in the can, and sometimes they like it, sometimes they don’t. It just depends. It’s one place I can still grow hair back, unlike the top of my head.

Senator Fred Thompson will speak at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Nashville on June 8 at 7 p.m.