Celebrating William Gay

A host of novelists, poets, teachers, and editors from around the country recall the genius of William Gay

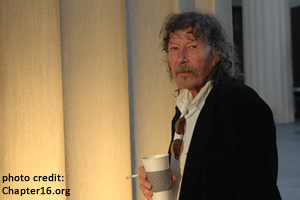

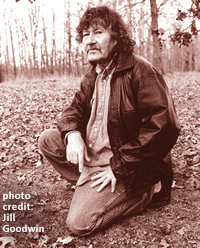

These are some well-known facts in William Gay’s official biography: that he lived in a cabin in the woods, that he didn’t use email, that he worked in construction his whole life until someone finally noticed he was a great writer. But these facts tell only part of the story.

For readers and writers, at least, the fuller story depends upon an eternal question: is a writer born, or is he made? William Gay was born a writer. As a late-life literary success who didn’t attend creative-writing programs or pay for professional workshops, Gay symbolized the hopes of struggling writers, especially rural ones. He was good, and he found a way to let the world know he was good—those are facts we cling to as evidence of what is possible. Throughout history, people have made long pilgrimages to witness lesser miracles.

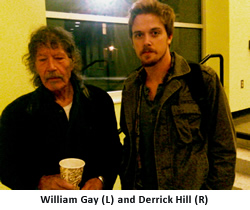

William Gay’s death last week of heart failure sent tremors through the community of writers and readers in Tennessee and beyond, people who loved him as a friend and as a writer. We have asked some of those who knew Gay, in ways large and small, to send us their stories. They come from New York City and from Wyoming, from Maine and from Virginia, and, of course, they come from Tennessee. Together, we hope these recollections—from Darnell Arnoult, Adrian Blevins, Sonny Brewer, Tony Earley, Robert Hicks, Derrick Hill, Suzanne Kingsbury, Randy Mackin, Inman Majors, Corey Mesler, Clay Risen, George Singleton, Brad Watson, and Steve Yarbrough—present a portrait of a man who will be greatly missed.

William Gay’s death last week of heart failure sent tremors through the community of writers and readers in Tennessee and beyond, people who loved him as a friend and as a writer. We have asked some of those who knew Gay, in ways large and small, to send us their stories. They come from New York City and from Wyoming, from Maine and from Virginia, and, of course, they come from Tennessee. Together, we hope these recollections—from Darnell Arnoult, Adrian Blevins, Sonny Brewer, Tony Earley, Robert Hicks, Derrick Hill, Suzanne Kingsbury, Randy Mackin, Inman Majors, Corey Mesler, Clay Risen, George Singleton, Brad Watson, and Steve Yarbrough—present a portrait of a man who will be greatly missed.

Today we also proudly publish here another excerpt from William Gay’s forthcoming novel, The Lost Country. Gay provided these excerpts in 2009, as companions to a long interview he gave Chapter 16, but we chose to publish only one of them at the time, holding the others in reserve to run in connection with some other news in Gay’s life—a big award, perhaps, or the announcement of a publication date for the new book. We include one of them here today, recognizing that the best person to provide the last word on William Gay’s gorgeous use of language and profound understanding of human nature is William Gay himself.

—Serenity Gerbman

Blurring the World Outside

Traveling with William Gay always involves a certain amount of detours

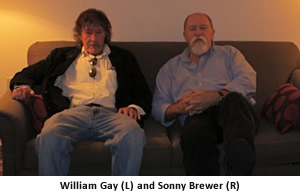

It goes like this: somebody somewhere asks either William or me to come and give a reading, and he or I say no or OK. If we decide to go someplace to do a book thing, give a talk, answer some questions from the audience maybe, then the road trip is on. We mark down the date and talk more and more on the phone about our trip. I’m like the coordinator guy because William does not much like to talk on the phone. Unless he wants to talk to you on the phone, which you will know if he picks up, and if he gets tired of talking on the phone he will say, My phone’s about to die. A half a minute later the call ends. Sometimes he will talk for an hour. On our road trips, we talk for hours and hours and hours. We miss our turns because the world inside the car forgets the world of streets and roads outside the car. On our way to Miami one time, driving east along the top of Florida on I-10, we looked up and saw the Atlantic Ocean outside the windshield.

What the hell have we done? I asked.

William said, We must have missed our turn.

But it was I-75 we needed to make a right on. That’s not some side street down a back road. It’s like ten acres of cloverleaf and signs and cars and lights on poles and nice landscaping.

I reckon we were talking, William said.

I reckon we were talking, William said.

I imagine so.

We’ve been half a day late on arrival. Like when we drove to Maine last September was a year ago.

We were supposed to go around New York City. But we were talking, and it was raining hard enough to shut down JFK airport that weekend. So we looked ahead of the car to see the George Washington Bridge and realized we were in rush-hour traffic. It was a four-hour detour for us.

Then there was this week’s road trip to East Tennessee. Only six hours from William’s home in Hohenwald to Lincoln Memorial University and a Monday night reading. I hit the road on Thursday and stopped off at my mama’s house to visit. She lives in the woods where a cell signal drifts in now and then on the wind, only to be snatched away with a gust. When the signal made it to my phone, there was a notice of messages. I listened. And no amount of talking with William has ever blurred the world outside for me the way the news—a message and a message and another message—of William’s death fogged-in reality for me.

I thought about turning around and going back home to Fairhope, down on the coast. But I believed I might then never go back to Little Swan Creek Road, where William lived. Ever. And that would not be the right way to fold our trip map and put it away forever in the desk drawer.

When William had called me to set up this last road trip, I told my wife I might skip it this time. But then I told her I don’t know how many more of these we’ll be allotted, William and me.

So, standing in my mama’s carport I told Darnell Arnoult at Lincoln Memorial University to sweep out the Alumni House, I’d be on time for our reading.

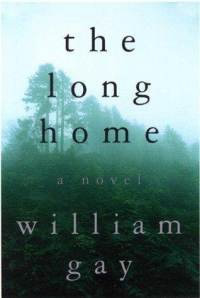

And, Monday night I read from The Long Home, William’s first novel. Two paragraphs of such power and beauty that I’d disbelieved him for a minute when he told me that to write it only took the length of time it took him to set it down. Until he told me he got it right in his head on the jobsite before going home that night to “set it down.”

Then I read to the room his essay, “Fumbling for the Keys to the Doors of Perception: A Memoir Mostly True But With Some Stretchers, as Mark Twain Once Said.” William writing about William. Not writing Fleming or Bloodworth. Him telling of working at the boat-paddle factory where he decided to quit, finally, and go off and find the words, the right and good words, for describing the way snow falls in the dark.

Then I read Ecclesiastes 12:5: “…because man goeth to his long home, and the mourners go about the streets.”

So that’s how it goes. We are left here to mourn while William’s gone home.

—SonnyBrewer (Fairhope, Alabama)

The Myth of the Drywall Hanger

William Gay did not climb down from his ladder and, having never read a book, decide he was going to write one

Let’s talk about the drywall-hanging.

Or not.

Every obituary I’ve read about William Gay—as was the case with every newspaper or magazine profile I read about William while he was alive—features his time in the carpentry trades, particularly as a drywall hanger, almost as prominently as it features his prodigious gifts and accomplishments as a writer.

Which smacks, or ought to smack, of condescension and snobbery—inadvertent usually, and most often well-intentioned, but condescension and snobbery nonetheless.

Based solely on the many thousands of words written about William’s pre-writing career as a carpenter one might come to believe that he was some kind of working class savant, a Rain Man of Letters; that an infinite number of drywall hangers had banged on an infinite number of typewriters until one of them accidentally typed The Long Home. The dark, unspoken corollary of this kind of reasoning, even as it purports to celebrate the man, is that the production of literature is still considered, as it always has been, an exclusive province of the elite. Any truly successful person such as, say, a major American literary figure, must be successful for a reason; likewise, the guy spackling your kitchen addition must be doing so because he isn’t smart enough to do anything more important. Who knows, maybe five hundred years from now, some misguided but clamorous band of second-tier scholars will waste time debating who really wrote the books of William Gay because, God knows, a drywall hanger from Hohenwald, Tennessee, with little formal education, would have been incapable of doing so himself.

Based solely on the many thousands of words written about William’s pre-writing career as a carpenter one might come to believe that he was some kind of working class savant, a Rain Man of Letters; that an infinite number of drywall hangers had banged on an infinite number of typewriters until one of them accidentally typed The Long Home. The dark, unspoken corollary of this kind of reasoning, even as it purports to celebrate the man, is that the production of literature is still considered, as it always has been, an exclusive province of the elite. Any truly successful person such as, say, a major American literary figure, must be successful for a reason; likewise, the guy spackling your kitchen addition must be doing so because he isn’t smart enough to do anything more important. Who knows, maybe five hundred years from now, some misguided but clamorous band of second-tier scholars will waste time debating who really wrote the books of William Gay because, God knows, a drywall hanger from Hohenwald, Tennessee, with little formal education, would have been incapable of doing so himself.

Pointing out that William Gay never went to college is as useless an exercise as pointing out that Bill Gates never finished. Education, like the production of literature, is ultimately the solitary pursuit of the diligent. William was able to write the extraordinary books he wrote because he had meticulously and passionately prepared himself, over the course of decades, to write them. He was an expert in twentieth-century Southern literature; he was a perceptive and infinitely knowledgeable music critic; the only people who maybe know more than William did about Bob Dylan and Cormac McCarthy are Bob Dylan and Cormac McCarthy. He was an inveterate patroller of literary magazines and devourer of fiction. I never saw him when he didn’t ask me if I had read this or that story in such and such a magazine, or what did I think of the work of so and so the blues musician. To be honest, I had almost never read the story; I was even less likely to know the work of the musician. He was, in short, in his fields of interest, in his areas of expertise, maybe the most impeccably educated man I ever met.

William did not climb down from his ladder and, having never read a book, decide he was going to write one. He climbed down from that ladder having read thousands of books. That singular education, patiently and privately obtained, enabled him to write novels that will retain the specific gravity of literature for as long as there are shelves to hold them. Because of those books, we’ll never completely say good-bye to William, but let’s lay to rest the myth of the drywall hanger. Which is more remarkable, after all, that a drywall hanger became a great writer, or that a great writer once managed to hang drywall?

—Tony Earley (Nashville, Tennessee)

Commitment

More than most writers, William was about one particular place, that clump of Middle Tennessee where he was born and raised, where he’d written, and written, and written, always to be rejected, until his breakthrough, late in life

I once asked William Gay what it was like to be a famous author in a small town like Hohenwald. Did his neighbors come around at odd hours, bug him for autographs? Did he get into conversations about his characters at the checkout counter?

He said he tried to lay low. But occasionally people did approach him. One day, he said, “This woman asked if I had someone who helped me with my writing. I said, ‘What do you mean by that?’ And she said, ‘Well, I knew your family a long time, and they’re not that smart. I knew you when you were younger, and you’re not that smart. I was wondering if you had somebody who took out the little words and put in the big words.’”

What really blew my hair back was how he told the story: he wasn’t offended, he didn’t laugh. He sounded hurt. William looked pretty hard, with a face that had gone eleven rounds with life, but he was one of the most sensitive men I’ve had the pleasure of knowing. It came out in his person, and even more in his writing.

What really blew my hair back was how he told the story: he wasn’t offended, he didn’t laugh. He sounded hurt. William looked pretty hard, with a face that had gone eleven rounds with life, but he was one of the most sensitive men I’ve had the pleasure of knowing. It came out in his person, and even more in his writing.

Above all, he was sensitive about place. More than most writers, William was about one particular place, that clump of Middle Tennessee where he was born and raised, where he’d written, and written, and written, always to be rejected, until his breakthrough, late in life, with The Georgia Review. Thinly veiled Hohenwalds and Lewis Counties served as the settings for his stories and novels. He had tried to move away. He had lived in New York after leaving the Navy; in the redneck ghettos of Chicago, working at a pinball-machine factory. Now, with his success, he could move to Sewanee, or Oxford, or Chapel Hill, or some other college town and take up with like-minded folks thinking like-minded thoughts and doing like-minded things.

He had lived for a while in Oxford, actually, but he’d moved back to Hohenwald, again. His family was there, and he said he couldn’t write anywhere else. “I don’t know what it is about that,” he told me. “I’m close to the place I grew up, and the countryside, the natural part of it, hasn’t changed.”

And here was that place, Hohenwald, kicking him in the teeth. It wasn’t the only time William hinted at how hard it was for him to be accepted as a writer in his community. Back before he started selling his work, folks in his own family thought it was a bit weird that he’d spend all his time writing.

There was something heroic about William. To write, to produce something lasting for the rest of us to enjoy, and maybe learn from, he submitted himself to ridicule, ostracism, odd looks in the convenience store. And for the better part of four decades, he batted a goose egg in that particular game. It’s easy to aspire to the life of a Brooklyn novelist or a Left Bank poet. But how many of us would have the perseverance, the commitment to art of a William Gay?

—Clay Risen (New York City)

Four Visions of William

At conferences and festivals, I liked to think of William Gay as Home Base in a strange childhood game of tag; we could always find each other and lose all the discomfort of trying to remain cordial to strangers

The first words William Gay ever said to me occurred in what appeared to be a ballroom inside the public library in Nashville. This was in October 2002, at the annual Southern Festival of Books. I stood uneasily near the beer station—scared, really—and William sidled up and said, “Tommy Franklin says you’ll help me beat up ____,” a writer who’d reamed William’s fine novel Provinces of Night in a published book review. He said, “I’m William,” and gave me that grin of his, that twinkle in his eyes.

I had just met Tom Franklin and didn’t recall ever saying I’d help anyone fight a critic, but I said, “Okay,” and started laughing.

“Nah, not really,” William said. “He just said we need to meet up.”

We were uncomfortable as slugs touring a salt factory, and it seems that—except for once—William and I were always thrown together in these situations. I like to think we considered each other Home Base in a strange childhood game of tag, that we could each find the other somewhere and lose all the discomfort of trying to remain cordial to strangers.

On this particular night in Nashville, said writer/critic showed up soon thereafter as I stood with William. He said, “Hey, George, always wanted to meet you, big fan, big fan…”

I said, “Thanks.” He didn’t acknowledge William, and I would bet he felt awful about misreading the novel. Within an hour, my big fan started calling me “Mike” for some reason. He called me Mike for the rest of the night. I never told him anything different.

I would look at William, who grinned and grinned. Somehow it meant that we had won this fight without ever throwing a punch.

We were in New Orleans at some kind of booksellers’ conference. The hotel was out from the main drags, way out by the Superdome. William knew that I wake up at 4:30 just about every morning, no matter what, especially out of my comfortable territory. This convention lasted three or four days, and each morning before the sun rose William called, or I called him, and we met up and smoked (and drank beer, sinners we) and talked about mysterious illnesses that might keep us from having to attend our own readings and whatnot. And Faulkner. And Cormac McCarthy. And dogs.

One morning we went downstairs and got on some kind of trolley that would take us into the French Quarter. William sat right behind the driver, a young, flamboyant African-American man who insisted on pointing out various landmarks of interest—levees, cemeteries, abodes. I sat across the aisle. The driver said, “Ohhhhh, now I’m going to point out a place that has the best bread in New Orleans. If y’all are looking for some fresh bread, this is the place to go.”

One morning we went downstairs and got on some kind of trolley that would take us into the French Quarter. William sat right behind the driver, a young, flamboyant African-American man who insisted on pointing out various landmarks of interest—levees, cemeteries, abodes. I sat across the aisle. The driver said, “Ohhhhh, now I’m going to point out a place that has the best bread in New Orleans. If y’all are looking for some fresh bread, this is the place to go.”

He pointed at a Subway restaurant.

I looked at William, who nodded, and glint-eyed, and smiled. Everyone behind us on the trolley had leaned out the open windows, wanting to know The Best Place Ever to Get Bread in New Orleans.

We got off the ride and drank a beer or two, and then William said, “I want to find that driver we had. I could listen to that guy talk all day, driving us around.”

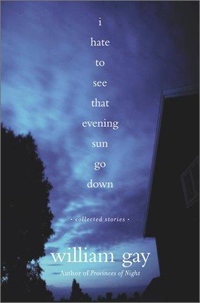

Later that night he and I read together. I thanked all the gods ever invented that I didn’t follow him. He signed my copy of I Hate to See that Evening Sun Go Down: “Best Always to Artemis Gordon.”

William and I shared Sonny Brewer’s basement in Fairhope, Alabama, because I wouldn’t stay with strangers at some kind of writers’ festival—I’d made it clear, I thought, that I couldn’t stay in the home of people I didn’t know, that no one would want me in their house—and the Holiday Inn was full. I had a couch, William the bed. I know for a fact that I said “Good night” every evening past midnight while William sat there reading, and every morning when I awoke, pre-dawn, William still sat there reading. Does he not sleep? I thought. No wonder it’s not a problem when I call him up his hotel room at 4:30.

I had a rental car and needed to get from Nashville to Memphis. William said, “Swing on by Hohenwald. Bring some bourbon.” I did.

At the time William lived in a house trailer on a nice piece of land. I pulled in, and his wonderful pit bull Knuckles came running out from beneath the trailer, barking like all get-out, looking mean.

At the time I had about eleven strays, a couple of them pit bull mixes. I got out of the car, and bent down small, and stuck my hand out. Knuckles wagged his stubby tail and came up to me. I petted his head and cooed.

William opened the door and shook his head. He grinned. “I used to think that dog was a good judge of character,” he said. “Hey, George, come on in. Did you bring that bourbon? Let’s listen to some music.”

I will miss the great big-hearted man immensely. We’re all going to miss the music he had to offer us generously.

—George Singleton (Pickens County, South Carolina)

Stopping at the Bookcase

When William Gay came to visit, it soon became apparent that there was no book in my collection that he hadn’t read

I first met William Gay when I was teaching at Motlow State Community College in Tullahoma. He had come to do a reading and, of course, had blown the doors off the place. Our students, most of whom worked full-time jobs in addition to going to school, reacted to him like they hadn’t with other visiting writers we’d had. These were rural Tennessee kids, and you could just see the whole world of books and writing opening up to them as he read from his novel, The Long Home. Here was a man who spoke as they spoke, who looked like someone they might have worked with or been related to, who had worked the same kind of jobs they had. It was as if a light had on gone on in their heads: This life I’m living, here in Tullahoma, working to make ends meet, is worthy of being told.

What they felt that night was what anyone felt who had the chance to spend a little time with William, namely that you were in the presence of something authentic. The real deal. After the reading, I invited William back to my house for a visit. He didn’t know me, but I mentioned that I had some beer and that I really liked Cormac McCarthy. These two facts seemed to do the trick. Back at my place, we passed through the kitchen, grabbed our beers, and headed toward the den. This proved an elusive destination for William because en route he had come across my bookcase. It was here that he stopped, or set up shop, rather. I went on in and put on some music, then joined him again in front of the books. For the next forty minutes or so, we stood there, never quite able to make it fully into the den, pulling out book after book and talking about it. We talked specifically about scenes we liked, and how the writing conveyed what it needed to convey. Three scenes I remember off-hand were: The turtle crossing the road in Grapes of Wrath (point of view), Rufus walking home with his dad after seeing the Chaplin movie in A Death in the Family (voice and tone), and Harrogate’s amorous adventure in the watermelon patch in Suttree (good ole-fashioned romance).

What they felt that night was what anyone felt who had the chance to spend a little time with William, namely that you were in the presence of something authentic. The real deal. After the reading, I invited William back to my house for a visit. He didn’t know me, but I mentioned that I had some beer and that I really liked Cormac McCarthy. These two facts seemed to do the trick. Back at my place, we passed through the kitchen, grabbed our beers, and headed toward the den. This proved an elusive destination for William because en route he had come across my bookcase. It was here that he stopped, or set up shop, rather. I went on in and put on some music, then joined him again in front of the books. For the next forty minutes or so, we stood there, never quite able to make it fully into the den, pulling out book after book and talking about it. We talked specifically about scenes we liked, and how the writing conveyed what it needed to convey. Three scenes I remember off-hand were: The turtle crossing the road in Grapes of Wrath (point of view), Rufus walking home with his dad after seeing the Chaplin movie in A Death in the Family (voice and tone), and Harrogate’s amorous adventure in the watermelon patch in Suttree (good ole-fashioned romance).

It soon became apparent that there was no book in my collection that he hadn’t read. And apparent as well that William had something very near a photographic memory. His recall was uncanny, and he was just damn smart. Eventually we did make it into the den, where my wife and a few friends were waiting. Seeing all my CDs in one convenient browsing spot, William plopped down on the floor and began looking at these. Again, there was no music I had that he wasn’t familiar with, be it John Lee Hooker, Coltrane, or Waylon Jennings. He smiled as he pulled out each new CD, sometimes offering a comment on its production or inspiration, sometimes just grinning fondly to himself as if he was seeing an old friend. I suggested he just go ahead and DJ for us, and this was an idea he could embrace. So that was how the night went on, a late late night as my wife just reminded me: William on the floor in front of the stereo, a bottle of beer beside him, some books he liked scattered about, and Bruce Springsteen’s The Wild, the Innocent, & the E-Street Shuffle cranking out into the night.

—Inman Majors (Harrisonburg, Virginia)

Behind Those Glorious Books

An inventory of little-known facts about William Gay

I met William Gay during a reading of The Long Home in 2000, and we became very close friends. As a literary demi-god, he often seemed not quite of this world, and yet the complexity and genius of his work matched equally who he was as a man. Because he was quiet and often introverted, I wrote a list of little-known (and a few widely-known) facts I learned about him. For those who would like to have known the man behind those glorious books:

When he was a little boy, he skipped school to write. If he didn’t have a pen, he used a walnut hull and a stick.

Karl Shapiro was a favorite of his, especially Car Wreck and Adam and Eve.

He smoked Marlboro Reds and didn’t mind a beer for breakfast.

He smoked Marlboro Reds and didn’t mind a beer for breakfast.

His characters were as real to him as you and I. He could point to every hollow and house that showed up in his work if you went to Hohenwald with him.

He went AWOL and tried to walk cross-country but was eventually sent back.

He loved Bobby Dylan and went to live in New York partly just to meet him.

Beautiful women chased him down the street for autographs.

He hung drywall for a living before he was published, and he and his partner were the “fastest drywall hangers in Lewis County.”

He loved Billy Bob Thornton and watched Bad Santa and Sling Blade almost every year.

After The Long Home was published, he said its success was due to Richard Howorth at Square Books and Johnny Evans at Lemuria, selling his books “practically by hand.”

He was extremely loyal.

The scenes from his fiction came to him fully-formed: he wrote them longhand and then typed them over again before he sent them out. Between the longhand and the typed version very little revision was ever needed.

Hollywood, specifically some of the cast from HBO’s Deadwood, wanted to make a movie of Provinces of Night, and William’s main reason for meeting them was to try to get his friend Tommy Franklin on the show.

He hardly ever drove and never flew.

You’d often find him at a local bar on Hohenwald’s main drag the night he was supposed to be at a reading. If you asked him to come along, he’d get a six pack to go and jump in the car.

He was shy.

He and Sonny Brewer once drove from Tennessee to Maine for a reading.

He kept his writing mostly a secret until he was first published at age fifty-five.

He did not like to edit other writers’ work because he didn’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings.

He knew where to find ginseng and picked it often on the hill behind his log house.

He declined The New York Times’s offer to come down and profile him for their Sunday edition because he didn’t much want his privacy disturbed.

He was also a visual artist—his medium was oil painting.

His last words to his daughter were, “Rick Santorum makes George Bush look like Abraham Lincoln.”

—Suzanne Kingsbury (Brattleboro, Vermont)

Sentences That Warmed the Air

A bookstore owner remembers William Gay’s first public reading

I first met William Gay when he came to our bookstore to sign his first novel. When he arrived no one would have taken him for the author. He looked like what he was: a modest man, a worker in sheetrock (go ahead, enjoy the metaphors embedded there). I greeted him warmly. I had just read The Long Home and admired it very much.

He was quiet, shy. He spoke in a whispery murmur that still carried that Old South weight in it. Almost a rasp, the singing the wind might use after a few belts of Jack Daniels. I asked him how he was. He told me he was scared to death. Apparently, if I am not misremembering, this was to be his first public reading. I did what I could to make him more relaxed. I told him it was his night and that he could handle it any way he wanted. Reading, no reading, whatever. He smiled a tight smile.

He was quiet, shy. He spoke in a whispery murmur that still carried that Old South weight in it. Almost a rasp, the singing the wind might use after a few belts of Jack Daniels. I asked him how he was. He told me he was scared to death. Apparently, if I am not misremembering, this was to be his first public reading. I did what I could to make him more relaxed. I told him it was his night and that he could handle it any way he wanted. Reading, no reading, whatever. He smiled a tight smile.

Of course he did read that night, and it was wonderful. His sentences warmed the air. And he was a hit, a major hit, with the crowd who came to hear him. There were others in attendance who had also read the novel, and comparisons, which would later become common, were batted about: Faulkner, Cormac McCarthy, Barry Hannah.

I saw William Gay a few other times at other author events. I wasn’t his friend but I felt a special affection for him. He seemed at all times, the way he did that first evening, like a humble and genuine fellow whose great gift of voice appeared even a surprise to him.

I paraphrase here what I heard said of another writer who died with books still in him: His passing makes me doubly sad. Not only no more William Gay, but no more William Gay books.

—Corey Mesler (Memphis, Tennessee)

The Real Thing

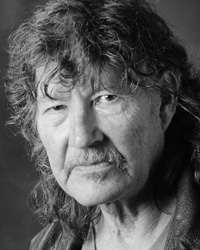

With his long curly hair, deep-set eyes, weathered face, and his entirely honest and unaffected gaze, William Gay struck me as one of the most formidable people I’d ever met

I first heard of William Gay during a phone conversation with Tom Franklin. “Have you heard of this guy?” Tom said. “He’s really good.” I had not. I got a copy of The Long Home as soon as I could, read it, and said to myself: Damn right, this man is the real thing.

The next year, during one of Sonny Brewer’s Southern Writers Reading gatherings in Fairhope, Alabama, someone told me William admired a story of mine in The Oxford American. Having been pretty much blown away by The Long Home, I was gratified and even humbled that this man had said he admired something I’d written. Someone with me pointed out William standing on the sidewalk near the entrance. I introduced myself and told him how much I admired his novel. William, his expression never changing, said in his beautifully uncorrupted Tennessee accent that he’d read my story.

“It’s a good story,” he said.

And that was it. He just looked at me without saying anything else, and I felt I was being sized up, that he was figuring on whether I was real or a phony. I didn’t know what to say.

As we were walking off, the friend with me said, “That was William Gay? He looks like an ax murderer.”

I didn’t think he looked like an ax murderer, although he certainly didn’t look like your average citizen on the street. With his curly long black hair, his intense and deep-set eyes, noble nose, weathered but not hard face, and his entirely honest and unaffected gaze, he struck me as one of the most formidable people I’d ever met. The man was always who he was, uninterested in altering himself to fit a moment or a scene. Even if being around gatherings made him a little uncomfortable, it had nothing to do with fear.

That night at the reading, William read the hilarious hog-pen scene from The Long Home. I couldn’t get over how well he read in his regular speaking voice, just loud enough to hear. He was one of the best readers I’ve ever seen and heard, up there in the ranks with the great Barry Hannah (who was number one, hands-down), and he seemed to do it effortlessly.

That night at the reading, William read the hilarious hog-pen scene from The Long Home. I couldn’t get over how well he read in his regular speaking voice, just loud enough to hear. He was one of the best readers I’ve ever seen and heard, up there in the ranks with the great Barry Hannah (who was number one, hands-down), and he seemed to do it effortlessly.

I saw quite a bit of William in Fairhope during the next two or three years, as Sonny was active in those days bringing people down for Southern Writers Reading gatherings. William generally walked quietly around, sipping a Budweiser. At some point he said, “I don’t usually do this, drink beer all day. I really don’t. When I’m home by myself and working, I don’t drink much at all. But these things make me kind of uncomfortable.” I believed him. I think I drank more at those things than William did.

The only time William and I spent some intimate and concentrated time together was after one of these events. He needed a ride back up to Hohenwald, and I was living temporarily in Birmingham those days, so I volunteered. Hohenwald is quite a bit farther north than Birmingham, but I wanted the time with William.

The drive must have taken six or seven hours. We talked some about music—I didn’t know that Will Oldham, known for his band Bonnie Prince Billy, was the same guy who’d played the young narrator of one of my favorite movies, Matewan, but William did. We talked about women. Both of us were seeing younger women and worried about the state of the affairs. At one point William said, “Sometimes I wish she’d just get it over with and dump me. I know it’s inevitable. It’s knowing that but not knowing when that kills me sometimes.”

That sounded, to me, like a William Gay story: straightforward, unsentimental honesty about love and heartbreak.

We talked about writers, and of course Cormac McCarthy came up. I said I wasn’t that keen on McCarthy’s first novel, The Orchard Keeper, because it seemed to me he hadn’t quite fully processed his Faulkner yet, hadn’t taken the influence and made a voice entirely his own. I said, “Some of my writer friends hear that and say they’re disappointed in me.” William gave me that steady look again, held it for a moment, and then said, “I am, too.”

We reached the trailer William was living in, near Hohenwald, with his two sons, well after dark. Inside, conditions were what you’d expect of three single men, very much men, living together in tight quarters. When I later heard that William had managed to purchase a cabin, the one he lived in till he died, I was happy to hear it. I don’t think he minded the trailer, but I’m glad he got to live in such a peaceful and cozy place in his last years. I never visited the cabin, but I’ve seen the interviews and photos of him there. I think it must have been a kind of paradise for William.

—Brad Watson (Laramie, Wyoming)

No Pretense

With William Gay, there was a real sense that he had survived this life by the skin of his teeth

It all began with a Christmas gift of Provinces of Night from my neighbors, Diana and Gary Fisketjon. I’m not sure which of them told me it was an important book, but coming from either of them it was high praise. Nor am I sure what I was already reading that Christmas, but whatever it was, I soon put it aside as I began to lose myself in William’s powerful, wonderful novel.

Of course, he was not ‘William’ for me in those days. He was still that odd, award-winning hermit of a writer who lived somewhere near Hohenwald. He was a brilliant, true-to-heart storyteller who stole my heart the way great writers had stolen it when I was young. But living relatively close, I assumed we would meet some day. In the meantime, I became a reader of all that was William Gay, and that was enough. If we ever were to meet, it would be on his terms. It would not be because I had somehow germed my way into his life.

Of course, he was not ‘William’ for me in those days. He was still that odd, award-winning hermit of a writer who lived somewhere near Hohenwald. He was a brilliant, true-to-heart storyteller who stole my heart the way great writers had stolen it when I was young. But living relatively close, I assumed we would meet some day. In the meantime, I became a reader of all that was William Gay, and that was enough. If we ever were to meet, it would be on his terms. It would not be because I had somehow germed my way into his life.

Lucky for me, a friend of William’s, Julie Gillen, decided we needed to get together. I first noticed how small he was, a kind of otherworldly fragility that fit with his writing. He was mischievous and funny. There was a real sense that he had survived this life by the skin of his teeth. He was a gentle, creative man who dared to learn to write and to write brilliantly, despite circumstances that were mostly hurdles to be overcome. And along with his passion for writing, there was his passion for music, for painting, for women. He was a bit of a character out of his own work.

He came to Franklin and did my radio show, reading a piece that was way too long. As I sat next to William and saw my producer trying to get me to cut him off, I understood there was something important happening as he mumbled through the piece. William was not just reading William. He was being William. There was no pretense.

Not too long ago, I set William up with Bob McDill after he told me how much he admired Bob’s songs. He wasn’t just making conversation. He insisted on quoting me way more of his favorite Bob McDill songs than I really wanted to hear at the moment. As he went through song after song, he stroked my dog, Jake, the way folks who love dogs touch them.

As with everyone who leaves us too soon, William leaves behind a family who will forever mourn his loss. As for us, we have our inheritance. William has left us his novels, his short stories, his essays, and all the rest.

Thank you, William. We are rich, indeed.

—Robert Hicks (Franklin, Tennessee)

Where Tension and Conflict Reside in Words

It’s easy to understand William Gay’s attraction to Appalachian landscapes—geographical or psychological

Over a year ago, I asked William Gay if he would consider coming seven hours from Hohenwald to Lincoln Memorial University in Harrogate, Tennessee, to give a reading, and he said he would. He said he had an affinity for Appalachian literature and culture. Then he added that he would like to visit Harrogate because Cormac McCarthy had named a character in one of his novels “Harrogate.” So a quest was born, and William invited his friend Sonny Brewer to take another long road trip. It’s a sad thing for LMU that William passed away just before leaving for East Tennessee to share his work and his stories about writing.

It’s easy to understand his attraction to Appalachian landscapes—geographical or psychological. William Gay’s work resonates with an Appalachian sensibility—the lament and yearning of fiercely independent characters, whether evil or innocent, who wrestle their environment as much as their history, or circumstance, or fate—rendered in his eloquent, speakerly storytelling. William’s fiction always rewards readers with a fine tale with plenty of action and suspense, but the reward extends beyond the tale or its characters to that most local level of word choice, well-crafted sentence, and well-honed paragraph, where tension and conflict reside in words themselves, where words rub up against each other to generate friction and cultivate intimate relationships with one another in both sound and subtlety, where the reader may be forced to the unabridged dictionary to learn more about their own native tongue. I look forward to returning to his books and stories throughout my lifetime.

It’s easy to understand his attraction to Appalachian landscapes—geographical or psychological. William Gay’s work resonates with an Appalachian sensibility—the lament and yearning of fiercely independent characters, whether evil or innocent, who wrestle their environment as much as their history, or circumstance, or fate—rendered in his eloquent, speakerly storytelling. William’s fiction always rewards readers with a fine tale with plenty of action and suspense, but the reward extends beyond the tale or its characters to that most local level of word choice, well-crafted sentence, and well-honed paragraph, where tension and conflict reside in words themselves, where words rub up against each other to generate friction and cultivate intimate relationships with one another in both sound and subtlety, where the reader may be forced to the unabridged dictionary to learn more about their own native tongue. I look forward to returning to his books and stories throughout my lifetime.

William Gay was a kind, generous, brilliant man. It’s sad to think about his novels and stories left unwritten. I’m thankful Sonny decided to make the trip to Harrogate and LMU anyway, with a photo of William Gay riding shotgun.

—Darnell Arnoult (Harrogate, Tennessee)

An Urgency and a Hard-Won Authority

William Gay knew everything about the will—the iron will—and human longing, too—and how ferocious these can be inside of us, and how important they are to heed

When I first read William Gay’s writing in the pages of The Oxford American about ten years ago, it was like I’d won some kind of lottery. I mean this. It was like first reading Faulkner or O’Connor or Welty or Roth or Virginia Woolf, even. There was a wholeheartedness on the page—an urgency and a hard-won authority, like lemons in frothy water. And there was an outright courage, too—a plucky refusal to flinch. Even where you could hear the McCarthy and the Faulkner—just a little bit, just here and there—there was something other there, something fully warranted and actual, hilarious and heartbreaking. Whatever-it-was was dangerous, too, it seemed like, and a bit fatal.

Robert Frost says that sentence sounds “are gathered by the ear from the vernacular and brought into books,” and that “the most original writer only catches them fresh from talk, where they grow spontaneously.” I think this idea might be tied to the equally romantic idea of sentence-sounds being—somehow—a manifestation of character. Or let’s just say that certain writers—the very best—find a way of coupling their (best) selves to the various idioms they live among, only then and meanwhile to demonstrate the new amalgamation on paper, thereby making the inert and invisible wake up and sing.

Such transformation happens, always, against great odds.

Such transformation happens, always, against great odds.

Always therefore it would be good, if you are a writer, to be obsessive, self-interested, and solitary-to-the-extreme—ferocious, over-confident, haughty, and rich, rich, rich, rich.

But what if you are the humble son of sharecroppers from Tennessee? What if you end up in Vietnam, rather than in pennyloafers at Yale? Or in some godforsaken submarine owned and operated by the U.S. Navy? What if you fall in love and have a bunch of kids? And write here and there, under the cover of darkness, in a kind of closet, just when you get a second, when you don’t have to chop wood or build a cabin or make a hundred dollars? What if after all of this and a goddamned divorce and heart sickness and I don’t know what-all, in terms of sorrows, you become, nevertheless, your best self?

What if years and years and years after this overtly unassuming beginning—out of your own audacity and hard work and sheer will—you finally find a way to manifest that keen sense of hilarity, observation, metaphor, music, image, wisdom, and story in the world?

Wouldn’t it just be the most wonderful thing?

After twelve months of begging and cajoling and sweet-talking, I met William Gay in person in September of 2010 when he finally agreed to come to Colby College to give a reading. Since he didn’t want to fly and didn’t drive, he got Sonny Brewer to bring him. It’s really a story for the annals, now: Sonny and William rolling through a torrential rain storm 2,000 miles from Southern Tennessee straight up through New York City to the woods of Maine to read for the very lucky students in the writing program at Colby.

You think the lesson is going to be direct and erudite—something about how to describe a landscape, say, without it seeming fake on the one hand or false on the other. But the lesson was much bigger than that for the students and my colleagues and me at Colby that day. It was about talent being something you can boil straight up through time like the little embers of an eventual exploding volcano. It was about the will—the iron will—and human longing, too—it was about how ferocious these can be inside of us, and how important they are to heed. It was about what might be done with a life no matter what and come what fucking may.

It was a blessing.

I write in a sad rush to thank William for that blessing—for the gift of himself he never gave up on—and to wish him straightforward ease wherever he is now, fishing off whatever sweet pier.

—Adrian Blevins (Waterville, Maine)

A Duty to Language

The purpose of a writer, for William Gay, was taking notes and recording the world

His books line a shelf at my home, and one of his landscapes hangs on a wall in my living room, and while those tangible objects—permanent in their own perfection—are sources of comfort in this period of loss, the intangible is what I already miss about my friend William Gay: phone calls, conversations, hilarious anecdotes on road trips, an encyclopedic knowledge of literature and music, all delivered in his unmistakable Tennessee drawl.

I’ve actually warned my students that they might not understand a word William said until they allowed themselves to be swept along by the particular cadence of his voice. But once they found that rhythm, something clicked like tumblers in a lock, and he charmed them all.

William never turned down an invitation to visit my classes at Middle Tennessee State University. While uncomfortable before large crowds at readings, he seemed to relish the opportunity to talk with students about his work and creative process, and had a way about him that put them at ease and made them feel their questions were important, that their opinions about his stories and novels mattered. For most of them, William was the first flesh-and-bone writer they’d ever met, and the experience was profound and memorable.

William never turned down an invitation to visit my classes at Middle Tennessee State University. While uncomfortable before large crowds at readings, he seemed to relish the opportunity to talk with students about his work and creative process, and had a way about him that put them at ease and made them feel their questions were important, that their opinions about his stories and novels mattered. For most of them, William was the first flesh-and-bone writer they’d ever met, and the experience was profound and memorable.

And yet, after every classroom visit—at least a half dozen—he always asked me, “Was that alright? Do you think it went well?” Those questions speak volumes about the man. William was genuine, unassuming, and humble—a rare combination of qualities in anyone, but especially in someone who possessed so many extraordinary gifts. He was always surprised when recognized in public, and I don’t think he ever quite accepted how valuable his work was or how far-reaching his literary influence.

Before his final trip to MTSU, William had just been asked by The Folio Society of London to write an introduction to their special edition of William Faulkner’s novel As I Lay Dying. He told me on the phone: Let’s talk about the novel on the ride to school. I knew I would have nothing to add that he hadn’t already contemplated, but it would be edifying to hear him organize his thoughts. I was his sounding board and learned more in a few hours than I ever did in a graduate seminar. I think he was honored to have been asked and was proud of that introduction—and he should have been: anyone who reads or re-reads Faulkner’s masterpiece should first savor William’s words. For a self-described non-academic, William’s commentary on As I Lay Dying is as sound as any criticism I’ve ever read.

On another visit to MTSU, William sat on a panel with poets Wyatt Prunty and Jeff Hardin, and short-story writer Tamara Baxter. He offered these thoughts that evening: “The purpose of an artist—whether it’s a writer, a poet, a musician—is taking notes; they record the world and then put their own spin of truth on it. The truth is the main element in art. I see my role as having a duty to the language, using the language as well as I can, and just finding every now and then something true.”

In every experience I had with William—in every line of his I’ve read and every conversation I was privileged to enjoy—the truth was always there: in his dutiful attention to language, in his riveting imagery, in his characters and their spot-on dialogue, in that painting at home, and in those books that we can return to when we’re seeking our own truths.

—Randy Mackin (Linden, Tennessee)

A Modern-Day Sage

Something in those dark, focused eyes made you think he possessed answers to questions that weren’t meant to have answers

I had the opportunity just over a year ago to interview William Gay for the Tennessee Literary Project. Near the end of the conversation, William said, “Writing should feel like it’s about something bigger than it is.” I have mulled over these words time and again. With William, it wasn’t only the work but the writer himself who seemed to be about something “bigger.”

I’m not exactly sure what that bigger thing was or that I’m meant to know for certain; I just know my visits with William will always retain a mystical quality. This isn’t because he was some flashy, eccentric character who was so far out there that he was untouchable—anyone who has spent any considerable amount of time with William knows he was quite the opposite—or that he had grandiose ideas he was determined to get across. He was the most humble, down-to-earth person you will ever meet, dirty jeans and all.

I’m not exactly sure what that bigger thing was or that I’m meant to know for certain; I just know my visits with William will always retain a mystical quality. This isn’t because he was some flashy, eccentric character who was so far out there that he was untouchable—anyone who has spent any considerable amount of time with William knows he was quite the opposite—or that he had grandiose ideas he was determined to get across. He was the most humble, down-to-earth person you will ever meet, dirty jeans and all.

Yet when you were around him there was something enigmatic that drew you in when he spoke, whether he was reading his work or talking about two of his favorites, Bob Dylan and Cormac McCarthy. Something in those dark, focused eyes made you think he possessed answers to questions that weren’t meant to have answers. An underlying awareness of unspeakable truths you hoped you would absorb through osmosis.

This is why I drove to Hohenwald every chance I got. Because out there, twenty minutes beyond any cell-phone signal, tucked away in a log cabin at the bottom of the residing hills, lived a modern-day sage. In the same interview for TLP, William said, “One of the things that is so interesting about writing to me, at least, is that it is so hard to explain. It’s like ephemeral, you can’t really get a grip on it, why you do it, or where it comes from.” I’m not sure where it came from either, but I’m glad he found it and decided to share it with all of us.

—Derrick Hill (Bell Buckle, Tennessee)

Saying Something Deeper

William Gay didn’t care about the trivial, either in life or in art

Last summer, at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, I saw William Gay for the last time. Before that day, I hadn’t seen him since 2005, when we had a long conversation in the bar of a Nashville hotel about writers and writing and editors and life. William was only at Sewanee for a day. He’d come up to take part in a panel discussion about Barry Hannah. As always, someone else drove him—in this case, Tom Franklin. Prior to the panel discussion, when I walked over to give him a hug, he said, “Can we step outside, Steve? There’s something I’ve been wanting to ask you.”

When we got outside, William told me that the previous year, in an off-handed remark, a fellow friend and writer had told him that I once called him “unpredictable.” He said, “I was wondering what you meant by that.”

When we got outside, William told me that the previous year, in an off-handed remark, a fellow friend and writer had told him that I once called him “unpredictable.” He said, “I was wondering what you meant by that.”

I didn’t recall having made the remark, though I’m sure that I did because the mutual friend is a fine person who doesn’t tell lies. And in any case, I knew what I would’ve been referring to, so I explained myself to William, reminding him that in 1999, when I was Grisham Writer in Residence at Ole Miss, he’d called my wife and me at least four or five times and asked if he could come visit us and spend the night and we always said yes, though he actually showed up only once. After the second or third time, I told him, we assumed that he might or might not come, and this was what I meant when I labeled him “unpredictable.”

“Oh,” William said with palpable relief, “so that’s all it was. I was scared you might be saying something deeper.”

William didn’t care about the trivial, either in life or in art. Every conversation I ever had with him was intense, in the same way that the stories in his brilliant collection I Hate to See that Evening Sun Go Downare intense. He once called me in California to discuss marriage, and the conversation lasted three hours. I said things to him that I have not said to anybody else, and I’m sure he did the same. We once sat in the bar at Oxford’s City Grocery and discussed Larry McMurtry’s novel Lonesome Dove for the better part of an afternoon, and I will never forget William’s last word on the subject. “I don’t care what anybody else says: that’s a great American novel.”

The quality I prized most in William, both as a writer and a person, was that he didn’t necessarily care what anybody else said, unless what they were saying was deeply considered, thoughtfully and humanely expressed. I knew him for thirteen years, and it was clear to me that he understood our time on this earth is perilously short and not to be wasted on trivialities. He put his days and his nights to the best possible use, crafting a body of fiction that will be read long after almost all of his contemporaries have been forgotten.

—Steve Yarbrough (Stoneham, Massachusetts)

[March 2, 2012 update: This feature was edited to add the essay by novelist Tony Earley.]

To read an excerpt from William Gay’s forthcoming novel, The Lost Country, please click here, and here to read an earlier excerpt from the same book.