The Generals and the Wars Between Them

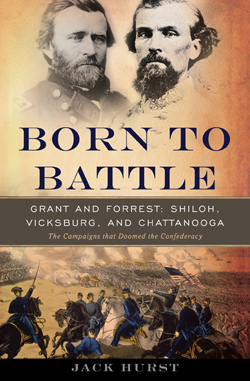

In Jack Hurst’s new look at Civil War leadership, the standouts are Grant and Forrest, who rose to the top in spite of—and also because of—their backgrounds

The campaigns and battles in Jack Hurst’s Born to Battle: Grant and Forrest: Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga–The Campaigns that Doomed the Confederacy have already been told by generations of historians, including Hurst himself, in his books on Nathan Bedford Forrest and on the Union victory at Shiloh. This time, however, Hurst’s narrative extends through West Tennessee and Mississippi down to Vicksburg, where Ulysses S. Grant had to confront the brilliant but unstable Sherman, his friend and confidante; the meddling politician-turned-general John A. McClernand; and a host of others who sometimes respected his orders and sometimes tried to undercut them and him.

At the same time, Grant also had to contend with public and political relations, Northern newspapers that demanded action and victory and were all too ready to cast blame for massive casualties and indecisive battle results. Meanwhile, cavalry-commander Forrest was raiding behind Union lines, and taking increasingly high-handed liberties with his superiors and their orders as he racked up successes and a reputation for resourcefulness, decisiveness, and “vicious valor.” After Union forces broke the Confederate stranglehold on the Mississippi with the victory at Vicksburg, both North and South concentrated on the Chattanooga vicinity in the fall of 1863 and 1864. The Union victory at Missionary Ridge, a surprise to both sides, left the South open to ruin, Sherman’s march through Georgia, and the Battle of Nashville, all of which sealed the Confederacy’s defeat.

At the same time, Grant also had to contend with public and political relations, Northern newspapers that demanded action and victory and were all too ready to cast blame for massive casualties and indecisive battle results. Meanwhile, cavalry-commander Forrest was raiding behind Union lines, and taking increasingly high-handed liberties with his superiors and their orders as he racked up successes and a reputation for resourcefulness, decisiveness, and “vicious valor.” After Union forces broke the Confederate stranglehold on the Mississippi with the victory at Vicksburg, both North and South concentrated on the Chattanooga vicinity in the fall of 1863 and 1864. The Union victory at Missionary Ridge, a surprise to both sides, left the South open to ruin, Sherman’s march through Georgia, and the Battle of Nashville, all of which sealed the Confederacy’s defeat.

Hurst is critical of many Confederate and Union commanders as slow, obstructive, and downright incompetent. The success of his heroes, Grant and Forrest, he attributes to their background. Neither was born to the social class from which the South, especially, tended to choose its leaders. Grant had been to West Point but made no special mark there or in the Mexican War. He was the son of a lowly tanner. After leaving the Army in 1854, he made an unsuccessful attempt to farm; at one point he was in such straits he was reduced to selling firewood on St. Louis street corners to feed his family. Well-bred Union officers continually sniped at and reported his heavy drinking. Forrest, too, came from undistinguished roots, though he had more success in life than Grant, accumulating considerable property and wealth as a slave trader. With no formal military experience, he bought his way into a command by recruiting and equipping his own cavalry battalion.

Because of the low social position of their parents, Grant and Forrest had to fight for advancement in the military establishment. Hurst argues that “Forrest’s treatment by his superiors suggests that a chief cause of the Confederacy’s death was insistence on blue-blood leadership.” This was a new kind of war, less civilized and restrained than the West Point textbooks taught. Grant and Forrest were the kind of men needed to fight it. “Hard lives had forced them to capitalize to the fullest on scant resources and watch out for the main chance,” Hurst writes. “Call it calluses.”

Because of the low social position of their parents, Grant and Forrest had to fight for advancement in the military establishment. Hurst argues that “Forrest’s treatment by his superiors suggests that a chief cause of the Confederacy’s death was insistence on blue-blood leadership.” This was a new kind of war, less civilized and restrained than the West Point textbooks taught. Grant and Forrest were the kind of men needed to fight it. “Hard lives had forced them to capitalize to the fullest on scant resources and watch out for the main chance,” Hurst writes. “Call it calluses.”

Born to Battle is a substantial book based on voluminous source material. Hurst narrates the many battles in considerable detail, though some readers will wish for maps, as well. There are a few here, but they are the kind Grant and Forrest themselves would have used and little help in following the action. That’s not the point of this book, however, and readers can find detailed battle maps online, in any case.

What Hurst, a Nashville historian, provides is more valuable: sociological and psychological context, and a smooth, real-time, narrative. He includes Grant’s and Forrest’s every movement, day-to-day, including details like the number of drinks Grant had in a two-week period and how his false teeth came to be thrown out with the waste water. Hurst uses Forrest’s uncouth and semi-literate rants and letters, brawls and battle wounds, to paint his image in cowboy colors, the kind of man who, when his horse is shot in the neck, reaches forward to plug the spurting blood with his finger. Hard to imagine generals like McClellan or Halleck doing that.

Jack Hurst will discuss Born to Battle at Burke’s Book Store in Memphis on June 14 at 5:30 p.m. and at Parnassus Books in Nashville on August 5 at 2 p.m.