De-Fictionalizing the South

Twenty-five years after the publication of his memoir about Southern politics, journalist James D. Squires talks with Chapter 16 about The Secrets of the Hopewell Box

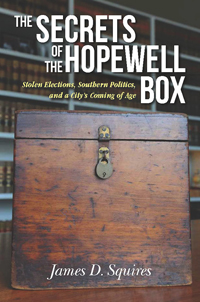

The post-World War II boyhood of James D. Squires in and around Old Hickory, a working-class community in the orbit of Nashville, gave him access to more than enough personal adventures and colorful charters for a classic coming-of-age memoir, which he finally wrote and published when he was past fifty. The Secrets of the Hopewell Box (Random House, 1996) was a local sensation, dealing as it did with the seldom-exposed underbelly of ward politics in a Southern city on the cusp of social change. The book got good regional and national exposure for a couple of years, but inexplicably the publisher let it go out of print. Now, Vanderbilt University Press has reissued it in paperback, giving readers a second chance to be entertained and instructed about a period of local history that had national implications in politics, civil rights, reapportionment, and the sensational federal trial of labor boss Jimmy Hoffa.

Jim Squires began his journalism career at The Tennessean as a bottom-rung reporter in 1962, when he was nineteen, and left ten years later, after earning a bachelor’s degree at Peabody College, serving as the paper’s Washington bureau chief, and spending a year at Harvard on a Nieman Fellowship. He joined the Chicago Tribune Co. in 1972 and subsequently headed its Washington bureau, edited its sister paper in Orlando, and returned to Chicago in 1981 as editor and executive vice president of The Tribune. He resigned at the end of the 1980s, leaving seven Pulitzer Prizes in the record. His parting shot was Read All About It! (Crown, 1993), a scathing critique of the corporate takeover of American newspapers and the elevation of profits over public service. Moving with his wife to a horse farm in Kentucky, Squires began writing books and breeding thoroughbred horses. A decade later, his horse Monarchos won an upset victory in the 2001 Kentucky Derby. He got a book out of that experience, too: Horse of a Different Color (Public Affairs, 2002). Recently Squires answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Jim Squires began his journalism career at The Tennessean as a bottom-rung reporter in 1962, when he was nineteen, and left ten years later, after earning a bachelor’s degree at Peabody College, serving as the paper’s Washington bureau chief, and spending a year at Harvard on a Nieman Fellowship. He joined the Chicago Tribune Co. in 1972 and subsequently headed its Washington bureau, edited its sister paper in Orlando, and returned to Chicago in 1981 as editor and executive vice president of The Tribune. He resigned at the end of the 1980s, leaving seven Pulitzer Prizes in the record. His parting shot was Read All About It! (Crown, 1993), a scathing critique of the corporate takeover of American newspapers and the elevation of profits over public service. Moving with his wife to a horse farm in Kentucky, Squires began writing books and breeding thoroughbred horses. A decade later, his horse Monarchos won an upset victory in the 2001 Kentucky Derby. He got a book out of that experience, too: Horse of a Different Color (Public Affairs, 2002). Recently Squires answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: You covered a lot of ground in your career after leaving The Tennessean. Almost twenty-five years later, you turned back here, to the Nashville neighborhoods of your youth—Old Hickory, Hopewell, East Nashville—to write this rambunctious account of free-wheeling political chicanery. What compelled you to do that?

James D. Squires: When I wrote Read All About It!, I signed a two-book contract, second topic to be decided by Random House, which then owned the imprint Times Books. Read became a regional best seller and then a textbook for j-schools.

Their choice of topic for the second book was “the sex lives of the national press” (mainly because they heard the L.A. Times media writer had signed to do that topic for Simon & Schuster). I hated the idea, and they came to hate it, too, after learning the S&S book had been canceled. Meanwhile, they had a smashing success with Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, which was published, promoted, and distributed in the same realm as Read All About It! The author declined to write a follow-up but suggested that a good town for a follow-up was Nashville. They asked me to do a Nashville book.

It just so happened that in an old, beaten-up briefcase was a fiction manuscript I had written as a Nieman Fellow at Harvard. It was called Nashville Stories, for which I had been given a substantial advance from a Boston publisher. I later gave the money back and decided to keep the stories as fodder for a novel. Random House loved the manuscript but wanted a nonfiction follow to Midnight, which was nonfiction.

So I followed up my second stint at Harvard, as a visiting professor in the Kennedy School, with a stint in the Seigenthaler chair at MTSU, during which I de-fictionalized my old manuscript and added new reporting on the Hoffa trial and the Baker vs. Carr reapportionment case. All of this I set into the framework of a book on Nashville and Tennessee politics, a story I had lived as a young boy growing up in the Robinson Garfinkle machine. All I had to do was interview people I had known all of my life.

So I followed up my second stint at Harvard, as a visiting professor in the Kennedy School, with a stint in the Seigenthaler chair at MTSU, during which I de-fictionalized my old manuscript and added new reporting on the Hoffa trial and the Baker vs. Carr reapportionment case. All of this I set into the framework of a book on Nashville and Tennessee politics, a story I had lived as a young boy growing up in the Robinson Garfinkle machine. All I had to do was interview people I had known all of my life.

Chapter 16: How do you classify this book? Is it verifiable history? Embellished history? Memoir? Expansive storytelling? A mix of these?

Squires: I would classify this book as a mix of memoir and political history. There is not an ounce of fiction in it, nor embellishment. However, an embellished and fictionalized piece of this history flowering from the Mink Slide chapter has been a work in progress for many years since and is now in the hands of a top fiction publisher that must go unnamed because as yet I do not have a contract.

Chapter 16: Some of the central figures in your book—Dave White, Jake Sheridan, Elkin Garfinkle, even Garner Robinson— are all but invisible in conventional histories of postwar Nashville politics, yet they clearly wielded enormous power and influence behind the scene. Looking back at Nashville now, almost two more decades after The Secrets of the Hopewell Box was first published, how would you characterize their contributions to our twenty-first-century form of governance, Metropolitan Nashville?

Squires: Dave White probably never influenced much of anything beyond his oldest grandson. But that political machine had a far-reaching effect on our country. Certainly its most lasting contribution was the Supreme Court decision in Baker vs. Carr, which Justice Earl Warren said was the most important case of his tenure, even more so than Brown v. Board of Education and the civil-rights cases. It resulted in the reapportionment of every elected body at all levels of government, producing two critical changes in democracy: the rise of the two-party South and the empowerment of black Americans. For the first time since Reconstruction, Republicans and blacks began getting elected to city councils, state legislatures, and Congress. Without this there would be no President Obama. Up until this point the highest ranking African American political leaders had been the appointment of a single member of the Supreme Court—Thurgood Marshall.

And how and why did this come about? Because a couple of these guys, mainly Elkin Garfinkle and Z.T. Osborne, saw the lawsuit as way to break the rural control of the State Legislature. Other than that, I am not sure they had any higher motivations. Certainly they would have harbored no thought of creating a Republican Party in the state. This is simply one of those unforeseen consequences that so often accompany major changes in society.

In fact, the voter approval of Metropolitan Government was aided by Baker v. Carr in a strange fashion. As a result, the growth of minority population in cities combined with white flight to the suburbs made it clear that the city political jurisdiction would soon be controlled by a minority, as quickly happened in Atlanta and Detroit. Some people quietly sold Metro as an idea that would preserve majority white political control of Nashville. To what if any degree this was true I have no idea.

For certain, Baker vs. Carr ended the white rural domination of state legislatures forever, which in turn changed the complexion of the House of Representatives in Congress as well.

Chapter 16: Apropos of nothing, I notice that you’re still “playing the horses”—as a journalist, an owner-breeder of thoroughbreds and, for all I know, as a two-dollar bettor. What could be more fun than that? Not writing books, certainly.

Squires: Music was my first love, writing my second. I fell in love with horses early in life but could never afford to own one until 1976. But I have been very lucky to have made a living raising them for better than two decades. And they have taught me patience when nothing else could.

Horses and women are God’s most beautiful creatures, not necessarily in that order. Old Colonel McCormick of Tribune fame once said that after his life in newspapers, he had come to prefer the company of dogs to men and books to dogs.

For me, after thirty years of newspapering, it was the company of horses to men and books to horses.