Freedom Turns Fifty

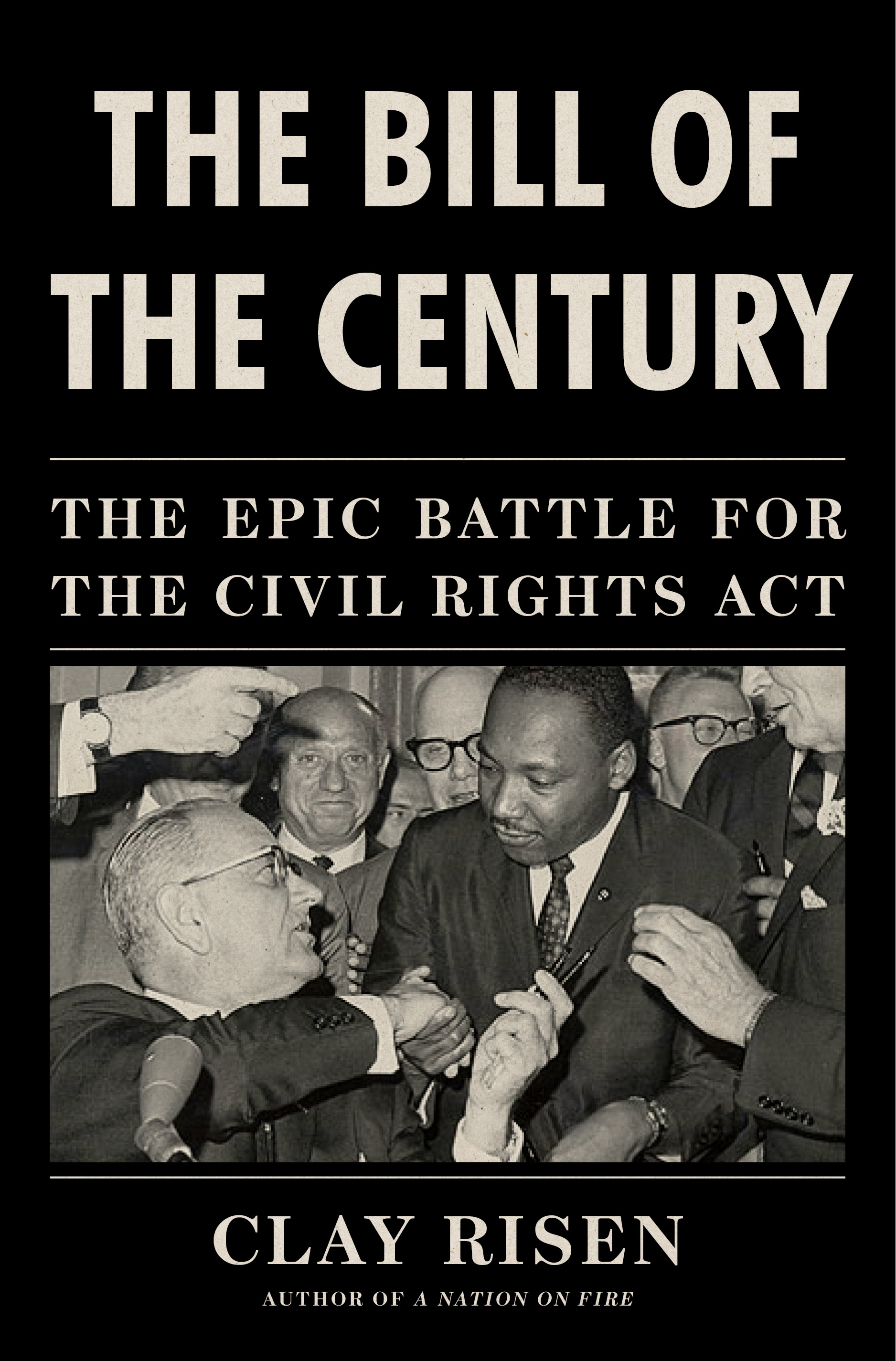

In The Bill of the Century, Clay Risen explores the fascinating twists and turns of groundbreaking civil-rights legislation

Fifty years ago this week, The Civil Rights Act languished in the U.S. Senate, victim of a seemingly endless filibuster led by Southern Democrats. Although the Senate had officially opened “debate” on the bill at the end of March, discussion was limited to hours-long speeches delivered to an increasingly empty chamber. Such procedural strategies and setbacks dogged the act that Clay Risen calls “the most important piece of legislation passed by Congress in the twentieth century.” Risen, a frequent Chapter16 contributor who grew up in Nashville and is now an editor on the op-ed page of The New York Times, garnered widespread praise for A Nation on Fire, his 2009 account of the riots that followed the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. He returns to the historic struggle for civil rights in The Bill of the Century: The Epic Battle for the Civil Rights Act, which delivers a penetrating account of the ultimately heroic effort to pass the landmark 1964 legislation.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 ensured fairness in the public sphere to all races at a time when the South remained heavily segregated, but its reach extended beyond race to include all creeds and both sexes as well. The Bill of the Century presents a fascinating, meticulously researched account of the political maneuvering required to achieve such sweeping legislation, from years of timid discussion under President John F. Kennedy through six months of bare-knuckled Congressional brawling under President Lyndon Johnson— a fight that culminated in Johnson’s signature on July 2. While the fiftieth anniversary of the Civil Rights Act has engendered a great deal of public discussion (Risen’s book is one of three new titles to address the topic), most historians have discussed the legislation as products of Johnson, who had championed a federal civil-rights act as senator and as vice president, and of King, who focused national attention on the need for reform. Risen’s approach is unique in identifying many smaller players who nonetheless made the act possible and in weaving their stories into a single narrative.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 ensured fairness in the public sphere to all races at a time when the South remained heavily segregated, but its reach extended beyond race to include all creeds and both sexes as well. The Bill of the Century presents a fascinating, meticulously researched account of the political maneuvering required to achieve such sweeping legislation, from years of timid discussion under President John F. Kennedy through six months of bare-knuckled Congressional brawling under President Lyndon Johnson— a fight that culminated in Johnson’s signature on July 2. While the fiftieth anniversary of the Civil Rights Act has engendered a great deal of public discussion (Risen’s book is one of three new titles to address the topic), most historians have discussed the legislation as products of Johnson, who had championed a federal civil-rights act as senator and as vice president, and of King, who focused national attention on the need for reform. Risen’s approach is unique in identifying many smaller players who nonetheless made the act possible and in weaving their stories into a single narrative.

“King and Johnson were great men,” Risen writes in his introduction, “and they played critical roles in the bill’s passage. But neither deserves all the credit, or even the bulk of it.” Arguing that a focus on King and Johnson “distorts not only the history of the act but the process of American legislative policy in general,” Risen sets out to correct the distortion. What emerges is a primer in the way big, controversial bills get passed in the United States—an unflinching tour of the inner workings of the sausage factory. In the process, Risen shows how even the most deadlocked Congress can manage to rise above partisanship for the good of the nation.

While any serious effort at civil-rights legislation had seemed all but dead in 1961, Risen notes that Attorney General Robert Kennedy began using an arm of the Justice Department, the Civil Rights Division, to enforce seldom-noted civil-rights laws that were already on the books. Recruiting some of the nation’s best and brightest young lawyers, Kennedy created an infrastructure that began to demonstrate how more sweeping federal legislation might be implemented in the future.

While any serious effort at civil-rights legislation had seemed all but dead in 1961, Risen notes that Attorney General Robert Kennedy began using an arm of the Justice Department, the Civil Rights Division, to enforce seldom-noted civil-rights laws that were already on the books. Recruiting some of the nation’s best and brightest young lawyers, Kennedy created an infrastructure that began to demonstrate how more sweeping federal legislation might be implemented in the future.

At the same time, the need for such laws was becoming increasingly clear, thanks to growing Southern intransigence in the face of desegregation orders and to the rising public outcry led by King. The wave of support that slowly swelled in America broke with the assassination of John F. Kennedy. The day after the president’s funeral, Johnson repeatedly brought a joint session of Congress and the Supreme Court to its feet with comments on Kennedy’s dedication to civil rights, and urged the crying, cheering audience, “The time has come for Americans of all races and creeds and political beliefs to understand and respect one another.” The stage was thus set for the passage of an act that had seemed dead in the water. But, as Risen makes clear, passage was by no means a certain thing.

Understanding the battle that followed involves invoking the rules of the House and Senate, negotiating the introduction of some 600 amendments, and observing back-room tactics by bill supporters and opponents alike. Risen proves an ideal guide to these complexities, delivering them in a clean prose style and finding key quotations that humanize the process. “If you ran a skunk across the floor and had ‘civil rights’ written on the side of it,” Rep. John Dowdy of Texas said of one version of the bill, “it would be the thing to vote for because it is called civil rights.”

In the end, Risen writes, the act as passed “did not put an end to American racism, nor did it eliminate the unique challenges of African American life. But it did much to alleviate both, and it reoriented the country—both the government and the people—onto a path toward true racial equality.” The filibuster that occupied the Senate fifty years ago this week was not broken until June 10, and the bill was passed nine days later. In showing how passage was achieved, Risen does more than explain where one path to equality began: he demonstrates how new paths to equality might still be walked today.

[This review appeared originally on March 31, 2014.]

Michael Ray Taylor teaches journalism at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He is the author of three traditional books of nonfiction—Cave Passages, Dark Life, and Caves—as well as The Cat Manual, an ebook.