A Slippery Bar of Soap in a Large Bathtub

Journalist Vince Vawter looks back on writing Paperboy, his first novel for children

After my debut novel, Paperboy, won a 2014 Newbery Honor, calls and emails began to filter in from writer’s groups and literacy organizations asking me to speak on the subject of children’s literature. Honored, obviously, I accepted all requests. But in the recesses of my mind, a question gnawed at me: what do I know about children’s literature?

On one level, the answer was obvious. Delacorte Press, a division of Penguin Random House, had marketed Paperboy as a middle-grade book, and it won a Newbery Honor from the American Library Association, recognizing “a distinguished contribution to American literature for children.” My label as an author of a children’s book was documented. The attention the book received surpassed all my fantasies, but I had this nagging secret: In the six years I worked on Paperboy, I never once thought of it as a “children’s book.”

On one level, the answer was obvious. Delacorte Press, a division of Penguin Random House, had marketed Paperboy as a middle-grade book, and it won a Newbery Honor from the American Library Association, recognizing “a distinguished contribution to American literature for children.” My label as an author of a children’s book was documented. The attention the book received surpassed all my fantasies, but I had this nagging secret: In the six years I worked on Paperboy, I never once thought of it as a “children’s book.”

Three years, ten hardback printings, and eight foreign-language editions later, I look back and realize that my naiveté was my deliverance: I was so green as a novelist that I knew nothing but to concentrate on telling my story, giving no thought to audience, marketing, or sales vectors.

To be sure, I wanted Paperboy to be a book that young people—especially young people who stutter—could read. Stuttering meant a lonely existence when I was growing up in the 1950s, and despite major improvements in therapy, it remains a lonely and confusing path today. I did want my words to make the stuttering life less lonely. But my story is about more than the vexations of a speech impediment. The confusion of segregation. Family dynamics. The cruelty and beauty of the urban South. Love that transcends all, especially race. The worth of an examined life.

My story is simple, I tell my audiences, but not simplistic. How many “children’s books” have introduced subjects such as Voltaire, existentialism, and metaphysics? At the other extreme, how many “books for adults” offer a unique perspective on Howdy Doody, Buffalo Bob, and Clarabell the Clown?

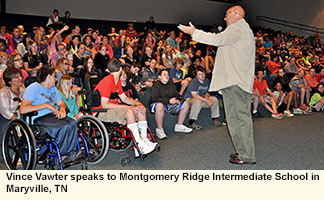

I have spoken in person or by video chat to more than a hundred schools, book clubs, and college classes since Paperboy was published in 2013, and I have learned something new about my own book—or my own life—from every session. While speaking to one book club, I mentioned how sad I was that I had lost contact with “Mam,” the character in the book who most resembles her real-life counterpart. One of the book-club members, a whiz on Ancestry.com, excused himself, went to his computer, and returned with a valuable clue about what might have happened to her.

But I’ve learned about far more than my own book and my own past. Those of us with grown children often view secondary education through the muddy lens of school-board policy, contract squabbles, and Test Assessment X versus Test Assessment Y. I have looked students in the eye in a dozen states. I have laughed with them. On occasion, I have cried with them. Hear what I say: while not everything is perfect, the kids are doing all right.

This goes for the middle-school students in Newtown, Massachusetts, who are graduates of Sandy Hook Elementary School. This goes for the students at the American School in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. This goes for grades four through eight in a one-room schoolhouse in Alberta, Canada, who video-chatted on a borrowed iPad. This goes for the students at Stanley Middle School in Lafayette, California, smack dab in the middle of Silicon Valley. These students’ questions and comments are insightful and reflective. They have not learned yet the art of pulling punches. Consider this one exchange from a middle school in Tennessee:

This goes for the middle-school students in Newtown, Massachusetts, who are graduates of Sandy Hook Elementary School. This goes for the students at the American School in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. This goes for grades four through eight in a one-room schoolhouse in Alberta, Canada, who video-chatted on a borrowed iPad. This goes for the students at Stanley Middle School in Lafayette, California, smack dab in the middle of Silicon Valley. These students’ questions and comments are insightful and reflective. They have not learned yet the art of pulling punches. Consider this one exchange from a middle school in Tennessee:

Student: Do you think you would have written your book if you didn’t stutter?

Me: Probably not.

Student: So in a way you could say that you’re glad you stutter?

Me: (Gulp!) I guess you’re right.

How’s that for fifteen-hundred dollars’ worth of therapy embedded in two questions from a seventh-grader?

For further proof that I am still a total rookie as a fiction writer, I offer another confession. For two years I told audiences from California to New York that there would not be a sequel to Paperboy. I had told my story precisely the way I wanted and was content to let it stand on its own. Then came a visit last year to a middle school in Florida, where a young reader cornered me at lunch and demanded to know what happened to the character in the book named Mr. Spiro. In the larger assembly that morning I had already explained that Mr. Spiro came totally from my imagination, so I reminded her that he wasn’t based on real people in my life like the book’s other characters.

A tear rolled down her cheek. “That’s exactly what I’m talking about,” she said. “You made him up once, and you can make him up again and tell us what happened.”

At various times in my newspaper career, I was called on to face legions of angry readers and go toe-to-toe with attorneys in federal courtrooms. I managed to hold my own in those situations, but I’m a total wimp when it comes to a seventh-grader with a tear on her cheek. By the time my plane touched down in Knoxville, I had written a rough outline for a sequel to Paperboy. I’ve been working steadily on the story ever since and hope to give the manuscript to my agent soon. Thank goodness I’m getting a little faster. A looming seventieth birthday tends to help one pick up the pace.

The sequel will rely even more heavily on fiction, but Mr. Spiro took care of that “problem” for me in the fifth chapter of Paperboy: “There is no difference between fiction and non-fiction in the world I inhabit,” he says. “I contend that one is likely to find more truth in fiction. A good painting after all is more truthful than a photograph.”

Though I didn’t start working on Paperboy in earnest until I had retired from newspapers, I can never remember not wanting to write it. Writing the sequel has not been as organic as the original, but once it got going, it consumed me with the same excitement. I would like to think my rookie days are behind me, but I’m not going to bet on it. Fiction is a slippery bar of soap in a large bathtub.

When I started giving presentations on children’s literature, I had to come up with something that might convince listeners I knew a little something of what I was talking about. To masquerade as an expert, I created Vince’s Three Rules for Writing a Children’s Book. To wit:

1) Don’t write a children’s book.

2) Tell a story that has never been told.

3) Write a book that has a reason to exist.

That’s really all I know. I just make up the rest.

Before turning to fiction, Memphis native Vince Vawter spent forty years as a newspaper journalist, including stints at the Knoxville News Sentinel and the now-defunct Memphis Press-Scimitar. He lives with his wife in Louisville, Tennessee, on a small farm in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains. His first novel, Paperboy, was named a 2014 Newbery Honor Book.