A Revolution Sown in Fields and Stewed in Kitchens

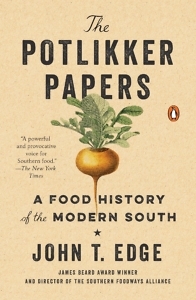

John T. Edge talks about The Potlikker Papers, the Nashville Reads title for 2018

In The Potlikker Papers, Southern foodways sage John T. Edge writes that some of the most significant civil-rights struggles of the twentieth century emerged at the South’s farms and restaurants. Later, he argues in the book chosen as the 2018 Nashville Reads title, those fields and kitchens were the scenes of a cultural renaissance that influenced the nation.

Edge finds a symbol for food’s transformative effect on Southern history in potlikker, the broth left in a pot where greens are boiled. Once dished out to enslaved people as a discardable leftover, the nutritious liquid is among the indigenous ingredients at the New South’s most inventive eateries. Edge, who writes for Garden & Gun and the Oxford American, is a winner of the James Beard Foundation’s M.F.K. Fisher Distinguished Writing Award and has been director of the Southern Foodways Alliance, based at the University of Mississippi, since it was founded in 1999. He talked to Chapter 16 by phone about his work.

Chapter 16: What is your earliest food memory?

John T. Edge: My mother’s vegetable soup, served in a teacup with cornbread crumbled into it ’til it was a delicious gruel of green beans and tomatoes and broth and cornbread. I was probably six. It reminds me of how Southern food is really at its best as a vegetable-driven cuisine, not some kind of strumpeted-up Paula Deen craziness that’s all about deep-fried this and deep-fried that. Southern food is at its core a farm-driven vegetable cuisine.

Chapter 16: You began your 2000 book, Southern Belly, with the statement, “Why I Wrote This Book And Why You Should Read It.” What would you say in a similar vein about The Potlikker Papers?

Edge: I wrote The Potlikker Papers to figure out my own obsession with Southern food culture, to see whether I could realize the truths that I think are embedded in our food, whether I could make arguments about racism and its imprint on the South, class difference and its imprint on the South, gender inequity and its imprint on the South. Whether I could identify the kind of arc toward justice and inclusiveness that I believe is a part of the Southern story.

I basically wrote the book to test my own hypotheses, and I wrote the book to make good on [the late Nashville writer and historian] John Egerton‘s belief in me and in the possibilities of food.

Chapter 16: In a letter to John Egerton’s publisher, Roadfood authors Jane and Michael Stern made claims that Egerton had plagiarized their work. Egerton, you write, “calmly and coolly proved them false.” You described what they were trying to do as a “colonial power grab,” an attempt to take “ownership of a place, its peoples and its institutions.” Egerton gave you the letters from that confrontation. How did they affect you and this book?

Edge: Not much. When I was first beginning to write about food I read [the Sterns] and was in part, not in full, influenced by them. I also recognized, in correspondence that coincided with the publication of Southern Food by John Egerton, and in a close read of their work, that the Sterns were colonialists of a sort who explored the South, plumbed its riches, and came back up to report about the provincial people and the provincial food of the region.

With some perspective and maturity under my belt, they rankled me. I have a deep and abiding respect for working-class farmers and cooks and waiters and waitresses. I think I have a responsibility to share their stories with as much honesty and regard as I’m able. On second and third reading of the Sterns, I don’t think they mustered the same stance.

Chapter 16: You address painful, shameful aspects of Southern history while telling the stories of the South’s food heroines and heroes, and some villains. How did the conflict between your love for the South and anger about its past lead you to the subject of food?

Chapter 16: You address painful, shameful aspects of Southern history while telling the stories of the South’s food heroines and heroes, and some villains. How did the conflict between your love for the South and anger about its past lead you to the subject of food?

Edge: I think it’s incumbent upon Southerners to hold both those ideas in their head at once: a profound love for this place and the people who claim it, and a critical anger for the errors in leadership many of our people have made. The complement of those two impulses, of love and criticism in equal measure, makes for a full and honest relationship with your place. I don’t mean for the book to be a kind of jeremiad against the region. I don’t mean for the book to be in any way punitive. But I do mean for the book to ask Southerners to look hard at our past and to reckon with the past and reckon with the ways that our past still affects our present and will affect, and might even limit, our future.

Chapter 16: You admire the regional food writing of Calvin Trillin. What other non-Southern writers seem insightful to you about Southern culture and food?

Edge: I really admire a younger writer at work today named Gustavo Arellano. Gustavo grew up in Orange County, California, in a Mexican American family and has earned perspective, by way of travel and a good ear for people, on the American South. Gustavo sees linkages between working-class Mexican-American culture and working-class white Southern and black Southern cultures. He writes a column for Gravy, the publication of the Southern Foodways Alliance, called “Good Ol’ Chico,” which is his play off “good ol’ boy.’ He opened my eyes to ways both cultures are subject to and suffer from stereotype. And the ways both cultures celebrate and embrace food as one of their primary cultural outputs, the way that Mexican Americans and Southerners define themselves through the music they make, the food they cook, the religions they worship.

Gustavo has challenged me to recognize the exclusionary stance I too often take. Think about the categories I’m using even right now, referring to Southerners and Mexican Americans. Those distinctions are a hindrance, not a help. I’m part of the problem, defining the groups in that way, because Mexican Americans are Southerners. They are not oppositional forces.

Here’s another way of thinking about that: one of the things I look forward to doing next when I’m in Nashville is going to this place south of the city that my friend Pat Martin told me about called Tennessee Halal Fried Chicken, which to me is reflective of future-tense Nashville in the making. In today’s Nashville, Tennessee fried chicken can be halal fried chicken, and that can define Southern fried chicken.

Chapter 16: Have you got a subject for your next book?

Edge: I’m puzzling through that right now. A question is beginning to form in my mind, although I don’t know if this will be the subject of my next book: is my fascination with immigrant culture in the South, and the promise I see in immigrant culture in the South, is that a diversion from the reality that schools are re-segregating in the South based on color and income? That life is in some ways re-segregating based on income and color? Am I so focused on the promise on the horizon that I’m denying the ways that old divisions are gaining new strengths?

That troubles me, and so I’m interested in writing about that, about the changing South, which is forever the subject that those of us who choose to write about the South write about. It is forever the morphing South that holds interest.

To read Chapter 16‘s review of The Potlikker Papers, click here,]

Peggy Burch was books editor at The Commercial Appeal in Memphis for ten years, and she also worked as a deputy metro editor and Arts & Entertainment editor for the newspaper. She is a graduate of the Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University and holds a master’s degree in English literature from the University of Mississippi.