The Senator in the Delta

Smyrna native Ellen B. Meacham chronicles Robert F. Kennedy’s crusade against poverty

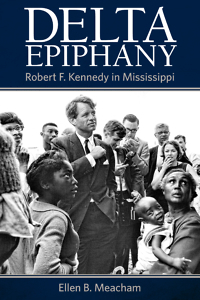

“It is very disheartening,” Robert F. Kennedy reported to his fellow senators after his visit to Mississippi in 1967, “when you see a child seven, eight, nine years old, an American child, and you ask him what he had for breakfast—molasses—and you ask him what he had for lunch and he didn’t have anything, and you ask his mother what she expects to feed him for dinner—and you find out it is going to be beans. That is what he is living on all the time, and they do not go to school. They cannot go to school, because, of course, they do not have any clothes.” In Delta Epiphany, Ellen Meacham tells the story of Kennedy, race, poverty, and politics at a difficult moment in American history.

A Smyrna native and award-winning reporter, Meacham also holds a master’s degree in Southern Studies from the University of Mississippi. She now teaches journalism at the University of Mississippi.

A Smyrna native and award-winning reporter, Meacham also holds a master’s degree in Southern Studies from the University of Mississippi. She now teaches journalism at the University of Mississippi.

Chapter 16: Bobby Kennedy has long been an object of public fascination due to his family, his political evolution, and his tragic assassination. In focusing on his April 1967 trip to the Mississippi Delta, what biographical aspects of the Kennedy story were you able to illuminate?

Ellen Meacham: I think an essential part of what makes Robert F. Kennedy so fascinating even now, both to the public and to biographers, is that he grew, both personally and as a leader, as he moved through his public life. Before he came to Mississippi, he had a mixed record on civil rights as Attorney General, but he had a deepening interest in helping the poor, and, because of the losses he had endured within his family, an authentic sensitivity to suffering. What he saw in Mississippi crystallized so much of that and gave him a sense of urgency. He just couldn’t shake what he had seen.

Chapter 16: What conditions did many African Americans in the Delta face?

Meacham: Most of the people in the Delta had been poor for generations, but 1967 was a particularly dire time for them. New farming practices, mechanization, and federal subsidies meant cotton growers needed fewer and fewer workers. In about two years in the mid-1960s, 24,000 people in Mississippi were suddenly out of work, and another 28,000, who had worked seasonally, also lost their livelihood and, often, their housing. At the same time, many Delta counties had switched from free commodity food aid to food stamps that everyone, even the poorest, had to purchase. This system left people with no work and no way to get food. Hunger, not just poverty, was deep and pervasive.

Chapter 16: How did powerful whites in Mississippi respond to Kennedy’s visit? How did they handle his call to address poverty and hunger in the Delta?

Chapter 16: How did powerful whites in Mississippi respond to Kennedy’s visit? How did they handle his call to address poverty and hunger in the Delta?

Meacham: The reaction of powerful white leaders ranged from denial to defensive outrage. They refused to believe hunger was a real problem. They argued that Kennedy was just trying to make headlines and get African American voters by picking on “poor Mississippi.” They even sent FBI agents to interview some of the people who spoke to journalists covering the hunger issue. However, behind the scenes, some of them did launch their own investigations of the issue and found similar results, and even made some efforts to change, but they never admitted it in public.

Chapter 16: Who are some of the poor black people that Kennedy met? Did his visit have any impact upon their lives?

Meacham: For the people in my book that Kennedy met—David White, Charlie Dillard, Catherine Wilson, and Brenda Luckett—his visit was a brief but vivid memory. It was a signal that someone with the power to command an audience and influence change saw their plight and cared. They weren’t used to that. It was, however, only one day in lives that were marked by daily struggle. Any changes that stemmed from his trip took a long time to work their way to Mississippi.

Chapter 16: One fascinating subplot in Delta Epiphany is the relationship between Marian Wright and Peter Edelman. How did each shape Kennedy’s involvement, and how did they carry on his legacy?

Meacham: Marian Wright (later Edelman) is, in a way, the heroine of the book. I was fascinated by her courage, determination, and conviction about speaking truth to power at such a young age—twenty-seven. She was skeptical of Robert Kennedy and his motives and wasn’t afraid to tell him and his aide, Peter Edelman, just that.

What she observed when they visited in 1967, though, changed her mind and her life. Peter Edelman was stunned at both the depths of poverty and this smart, strong, courageous, lovely young woman leading the charge.

Over the past fifty years, they have advocated for the poor and remained active and committed to their convictions. Most recently, Edelman was working the halls of Congress during the budget process, and successfully pushing for the renewal of the Children’s Insurance Program.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.