A March to the Mountaintop

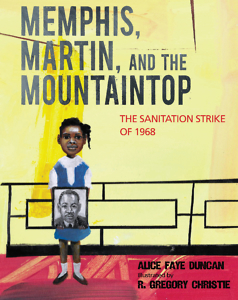

Alice Faye Duncan’s picture book tells the story of MLK’s last days in Memphis

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This interview originally appeared on August 23, 2018.

***

Ten years ago, librarian and writer Alice Faye Duncan went to the shelves to find a children’s book on the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. for a talk she was preparing. There was no such book. In fact, there were very few titles featuring any African American protagonist and even fewer about the civil-rights era. By that time, Duncan had already been awarded the NAACP Image Award for an Outstanding Literary Work for her now-classic picture book Honey Baby Sugar Child, just one of the titles she has published for children. Clearly she was the writer for the job.

Though Duncan’s initial storyline for Memphis, Martin, and the Mountaintop changed considerably over the next decade, her dream of creating a book that would ring out with beautiful language and the powerful story of civil-rights history never wavered. She answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Though Duncan’s initial storyline for Memphis, Martin, and the Mountaintop changed considerably over the next decade, her dream of creating a book that would ring out with beautiful language and the powerful story of civil-rights history never wavered. She answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: In a recent article, you wrote, “Big dreams and important work can demand long gestation periods.” How did your vision for this book change during its gestation?

Duncan: I live in Memphis. So my first impulse to write a story about the Memphis Sanitation Strike of 1968 began with primary sources: I scheduled an interview with photographer Ernest Withers. This was in 2006. We spoke in his Beale Street studio, which was filled with stacks of photographs from the floor to the ceiling. Ernest Withers photographed the famous picture of Memphis sanitation workers in front of Clayborn Temple Church on March 28, 1968. In the picture, striking men gathered for the protest that was led that day by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

When I was a child, I worshipped at St. James A.M.E. in North Memphis. I knew Mr. Withers then as the freelance photographer who visited our church to take pictures on special occasions like “Choir Day,” night revivals, and funerals. In 2006, after we traded remembrances of church secretary C.V.F. Burrow and Rev. Henry Logan Starks, Mr. Withers entertained my questions about the Memphis strike. Together we searched stacks of photographs while he identified faces, locations, and the drama unfolding at the moment of various shots.

Before I left that day, Mr. Withers gifted me a personal copy of his book, Let Us March On! Selected Civil Rights Photographs of Ernest C. Withers, 1955-1968. I gleaned from his pictures that the leaders of the Memphis strike and participants of the protest were mostly black men. Therefore, when I sat down to draft a children’s book about 1968, my main character was a black boy—eight years old.

From 2005 to 2015, I wrote many iterations of my story. With every new draft, the main character was a boy. In one version, a male child finds a strike sign in his grandfather’s attic. In another version, a grandfather finds a strike sign in the attic and uses the discovery to share his personal history with his grandson. In a third version, a boy wrestles with anger because his father is a striking sanitation worker and there is no money in the home for a new winter coat, school shoes, or a baseball glove.

I submitted some form of these three stories to a variety of publishers over several years. Each draft was rejected. I finally turned a corner and my story changed directions in 2015 when I phoned Dr. Almella Starks-Umoja to report on my writing progress. Almella is a Memphis educator. When she was a teenager, she participated in the Memphis Sanitation Strike with both of her parents. Her father, Rev. Henry Starks, was the pastor of St. James. He also served sanitation workers as a strike strategist. With donations from his church, he helped the striking men in his congregation pay rent and utility bills.

I submitted some form of these three stories to a variety of publishers over several years. Each draft was rejected. I finally turned a corner and my story changed directions in 2015 when I phoned Dr. Almella Starks-Umoja to report on my writing progress. Almella is a Memphis educator. When she was a teenager, she participated in the Memphis Sanitation Strike with both of her parents. Her father, Rev. Henry Starks, was the pastor of St. James. He also served sanitation workers as a strike strategist. With donations from his church, he helped the striking men in his congregation pay rent and utility bills.

I have known the Starks family my entire life. When I called Almella to lament the reception of one more perfunctory rejection notice, she said that I was writing an important story and, no matter what, I should stay the course. With her disdain for defeatist talk, Almella changed the subject to tell me about that night during the Memphis strike when she slipped away from home after 7 p.m. to wash her clothes during a city curfew. As the National Guard patrolled Memphis streets, her daddy risked his safety and rushed to the nearby laundromat where Almella sat alone waiting for the dryer to stop.

I grew up hearing Rev. Starks speak about the Memphis strike from the pulpit. And on numerous occasions, I had grilled Almella about that stormy night she heard Dr. King deliver his last sermon at Mason Temple. I thought I had heard Almella’s best stories. I had not. Several days later, I called her again with specific questions about 1968. We spoke on the phone for four hours. I took notes. And what began as a prose piece about a little boy morphed into a collection of thirteen vignettes about Lorraine Jackson—a little girl whose entire family sacrificed time, money, and comfort to support the Memphis strike in 1968.

Conversations with Almella revealed what I did not quickly glean from photographs. Black men led the Memphis strike, but the sixty-five days of protest proved successful because entire families supported the strike efforts. Men, women, teenagers, and small children marched in the Memphis streets, boycotted downtown stores, and participated in the nightly strike rallies. “I AM A MAN” was the resounding message coming from black striking workers. But without support received from local black women and children in their homes and community, it is likely the Memphis protest would have failed.

Chapter 16: Lorraine Jackson is a fictional composite of Almella Starks-Umoja and your own experiences growing up in Memphis. What were the challenges or benefits of working from real life in creating a fictional character?

Chapter 16: Lorraine Jackson is a fictional composite of Almella Starks-Umoja and your own experiences growing up in Memphis. What were the challenges or benefits of working from real life in creating a fictional character?

Duncan: Dr. Almella Starks Umoja inspired my character, yet Lorraine is not Almella. In my story, Lorraine’s parents are unschooled laborers. Almella’s parents were college graduates. Lorraine’s daddy is a striking worker. Almella’s daddy was a college professor and strike supporter. When drafting a character that is inspired from real life, the challenge is to compose a personality that inhabits the energy and timbre of the living, while remaining completely distinctive from the personality that inspired it.

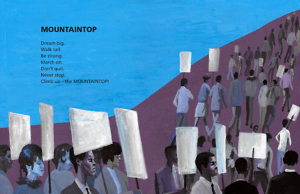

Chapter 16: This book mixes poetry and prose. Are there particular benefits to young readers from a cross-genre approach like this?

Duncan: I write books that I want to read. My two paragons of excellence are Gwendolyn Brooks and Eloise Greenfield. I like quick, snappy poems. I like rhythm. And while I don’t read music, and my understanding of bars is nil, I know that young people love music, too. With Memphis, Martin, and the Mountaintop, I have been intentional in my attempt to write a book that sings like a song. To this end, between Lorraine’s personal narratives, I have placed short poems that demand to be spoken aloud, remembered, and shared with others. My aim in this book is to move the reader aurally, emotionally, and intellectually. Did I achieve my goal? We shall see.

Chapter 16: The illustrations by R. Gregory Christie are gorgeous. How much input did you have in creating the art for the book?

Duncan: My editor allowed me to share my ideas about Gregory Christie’s illustrations when the book was complete and ready for the printer. While my suggestions were minor, my editor listened to me, and changes were made. You will notice that the illustrations appear to float. Nothing on the page seems grounded. Several faces appear to ripple into the background like waterfalls. While in New Orleans, I heard Gregory explain to a group of librarians that he painted the pictures in this way because the narrative is a collection of Lorraine’s memories. And often memories, like dreams, are not crystalized but fuzzy, foggy, unfocused.

Chapter 16: With its timeline and museum recommendations, this book is beautifully set up for classroom or home-education use. What advice would you give to teachers or parents for discussing the climax of the narrative, King’s assassination?

Duncan: It was Coretta Scott King who said, “Struggle is a never ending process. Freedom is never really won. You earn it and win it in every generation.” Children from each generation must assail injustice to apprehend freedom and democracy for all. Freedom is never free or without sacrifice. The rich and powerful do not concede power without a demand. Therefore, Dr. King’s assassination allows teachers and parents to broach a conversation about social justice, the efficacy of nonviolent protest, and the historical impact of one martyr’s life and death. Death is not an easy subject, no matter how it happens. And yet history bears witness that a grand and shining ideal like freedom stands resolutely on the tombs of the dead.

Chapter 16: How have school-library collections changed since you first noticed the absence of a book like this one?

Duncan: Here are some staggering numbers of a heartbreaking reality. According to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin, U.S. publishers released 3,500 books for children in 2017. Of these books, 340 were about or concerned the history of African American children. And from this number, African American authors wrote 122 books. Sound dismal?

The dearth was even greater when I poised myself to write about the Memphis strike. U.S. publishers released 2,800 books for children in 2005. Of these books, 149 were about or concerned the history of African American children. And from this number, African American writers wrote 75 books.

The organization “We Need Diverse Books” is using the influence of writers, teachers, and librarians to inspire change in publishing. In the meantime, I follow the small imperceptible voice that compels me to write. It is my opinion that the stories I am seeking are also seeking me. Here is a list of stories that have found me:

Memphis, Martin, and the Mountaintop will make its official debut on August 28, the fifty-fifth anniversary of the March on Washington. Sterling Press will release Twelve Days of Christmas in Tennessee on September 4. Told in a series of postcards, this is the story of two cousins in ugly Christmas sweaters who travel the state in search of famous history-makers, inspiring Tennessee land formations, and thrilling tourist attractions.

A Song for Gwendolyn Brooks will debut on New Year’s Day 2019. This collection of nine poems explores the life and times of Gwendolyn Brooks, the first black author to win the Pulitzer Prize. Brooks mastered the technique of writing sonnets. She then wielded her words to express the love, laughter, and loss of Americans in general and black folks specifically.

Here is my reality. With or without an offer to publish, I am always found writing. I am always found researching. I am always found ready and waiting for histories and words that seek to be found.

Sarah Carter is a high-school English teacher living and working in Lebanon, Tennessee. She is currently an M.F.A. candidate at the Sewanee School of Letters.