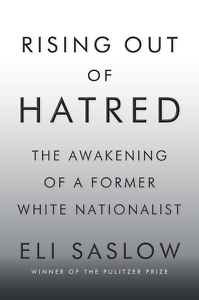

Leaving White Supremacy

Eli Saslow’s Rising Out of Hatred recounts one man’s confrontation with his own racism

Derek Black was the crown prince of a racist kingdom. His father, Don Black, founded Stormfront, the online network for a global community of white supremacists. His mentor was David Duke, the former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. By the time he was a teenager, Black was speaking at conferences of white nationalists, being interviewed by major media outlets, launching an online radio network, and starting a children’s page for Stormfront.

But as Eli Saslow grippingly chronicles in Rising Out of Hatred, Derek Black ultimately renounced his claim to the throne. In 2008, Black had won a seat as a Republican committeeman in Palm Beach County, Florida, by going door-to-door, decrying Hispanic immigration and African-American crime. By November of 2016, he was writing a New York Times op-ed titled “Why I Left White Nationalism.” He warned that “more and more people are being forced to recognize now what I learned early: Our country is susceptible to some of our worst instincts when the message is packaged correctly.”

Black himself had helped inject white nationalism into mainstream politics. “Which way are the Republicans going to go?” he asked at a 2008 “white rights” conference in Memphis. “I’m kind of banking on them staking their claim as the White Party. We can infiltrate. We can take the country back.” Raising the specter of “white genocide,” he called for an all-white United States. But his message avoided racist slurs and violence. Instead, he coated his arguments with the veneer of rationality—pseudo-science, flimsy history, and cultural resentments about a changing nation.

Rising Out of Hatred is a drama in three acts. The first brings Black, who was home-schooled, to New College of Florida, a public liberal-arts institution in Sarasota. His quest for higher education forced him into a double life. He considered immigrants from Latin America a scourge, but his first college friend was a Peruvian immigrant. He had once written that “Jews are the cause of all the world’s strife and misery,” but he started dating a Jewish woman. He escaped notice for a time. Then, while he was studying abroad in Germany, New College’s all-student email forum unmasked him as a leading light in the white-nationalist movement.

The second act details Black’s painful, halting evolution. Even as he was planning a Stormfront conference about how to debate liberals, his older intellectual framework was crumbling. Like many white supremacists, he romanticized Medieval Europe, but as he engaged in serious study, he saw the flaws in treating that epoch as a triumph of the white race. Meanwhile, most students considered him persona non grata, and some protested his continued presence at the school. A few others resolved to convert him with kindness, inviting him on sailboat rides or to Shabbat dinners.

The second act details Black’s painful, halting evolution. Even as he was planning a Stormfront conference about how to debate liberals, his older intellectual framework was crumbling. Like many white supremacists, he romanticized Medieval Europe, but as he engaged in serious study, he saw the flaws in treating that epoch as a triumph of the white race. Meanwhile, most students considered him persona non grata, and some protested his continued presence at the school. A few others resolved to convert him with kindness, inviting him on sailboat rides or to Shabbat dinners.

Eventually Black reconsidered the costs of his ideology. Most important in this transformation was his budding relationship with a classmate named Allison. It was a thorny bond, to say the least. There was an indisputable chemistry between them, but Black’s past repulsed her. In time, he left his radio show and website, and he abandoned his racist ideology. Allison, however, prodded him to make a public renunciation of white nationalism. “Your public beliefs oppress and hurt others,” she told him. “I don’t think there are nice ways to say that.”

Rising Out of Hatred’s final act concerns Black’s personal reckoning in the aftermath of his change of heart. Don Black had admired his son as a smarter, more disciplined version of himself. In the face of Black’s conversion, he felt a personal betrayal. The rest of the family saw Black as a dupe or a traitor. “For the Black family, white nationalism wasn’t just a belief system,” writes Saslow, “it was the glue that held together friendships and family.” Derek’s entire identity had been rooted in the movement he was rejecting.

Saslow, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for The Washington Post, narrates this story with spirit and nuance. Derek and Allison granted him access to their private emails and messages, providing an intense, intimate glimpse into Black’s political awakening.

After these upheavals, Derek sought anonymity. But he cooperated with Saslow after witnessing the Obama birther movement, the racist backlash to Black Lives Matter, and the intensified demonization of Muslims and Latin American immigrants—especially during the 2016 presidential election. The principles of white nationalism, once on the far-right fringe, were entering the mainstream. “Mr. Trump’s comments during the campaign,” he wrote in his op-ed for The New York Times, “echoed how I also tapped into less-than-explicit white nationalist ideology to reach relatively moderate white Americans.” Black had to speak out; his old movement was succeeding.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.