Against the Odds

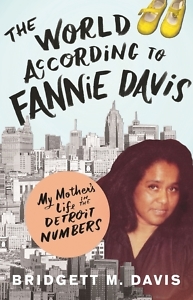

The World According to Fannie Davis is full of history, luck, and love

“I like the word ‘hit,’ its imagery of striking bat against ball for the win, of landing a great idea,” writes Bridgett M. Davis in her compelling new memoir, The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother’s Life in the Detroit Numbers. “It conjures up a hero’s triumph, and my mother is the hero of this story. Her win is mythic in our family lore.”

The World According to Fannie Davis is the story of an African-American striver—a migrant from Jim Crow-era Nashville who moved her family north to Detroit. After a couple of desperate years, living hand-to-mouth, Fannie concocted a plan to take numbers in Detroit’s underground lottery, a system called the Numbers. From her living-room table, Fannie operated a successful, if illegal, business. It was successful enough that she could often act as her own bank. In doing so, she taught her children, especially her daughters, that they could dream big and create their own luck.

Fannie Davis is many things—a history of Detroit in its heyday, a sociology of black migrant culture, and a taxonomy of the underground lottery of Fannie’s era. Davis interviewed family members and conducted research, excavating Fannie’s life and times. But the book is not academic in tone. Davis’s account of her mother’s life and business is first and foremost a loving memoir.

Fannie had a “dogged pursuit of happiness,” Davis writes, and was generous with lavish gifts, surprising Davis with a “brand new, canary yellow Sunbird” on her sixteenth birthday. For Fannie, generosity was an extension of pride. In the opening scene of the book, Davis’s first-grade teacher, a white woman, derides her for having so many pairs of shoes. In response, Fannie drives young Bridgett downtown to Saks and buys her another pair—yellow patent leather, impossible not to notice.

Before Fannie started taking Numbers, her story was a familiar one. She left Nashville and almost her entire family in the last wave of the Great Migration. From her father, she inherited an entrepreneurial spirit, and despite her family’s dire conditions in Detroit, she refused to work menial jobs, instead cultivating her knowledge of the Numbers. “If you’re going to work hard,” Fannie later told her daughter, “you might as well work hard for yourself.”

Fannie Davis is also a lesson in history. From as far back as the late eighteenth century, the Numbers has been part of an African-American tradition of “playing to better one’s conditions in a society that has systematically subjugated its black population,” according to Davis: when anti-lottery laws were enacted in the mid-1800s, authorities were attempting to “thwart the efforts of free blacks to acquire wealth-based equality.” The informal lotteries gave migrants like Fannie Davis access to opportunities. Many opened legitimate businesses, paid college tuitions, and supported the NAACP and the Urban League. The Numbers kept black money circulating in the black community.

Fannie Davis is also a lesson in history. From as far back as the late eighteenth century, the Numbers has been part of an African-American tradition of “playing to better one’s conditions in a society that has systematically subjugated its black population,” according to Davis: when anti-lottery laws were enacted in the mid-1800s, authorities were attempting to “thwart the efforts of free blacks to acquire wealth-based equality.” The informal lotteries gave migrants like Fannie Davis access to opportunities. Many opened legitimate businesses, paid college tuitions, and supported the NAACP and the Urban League. The Numbers kept black money circulating in the black community.

But even though Fannie could afford the family’s necessities, she couldn’t always acquire them. Unable to finance a mortgage through a bank, for example, she had to buy the family home “on contract,” with the help of a family friend, whose name appeared on the contract as the purchaser. “Bootstraps?” Fannie would say. “Hell, they do everything they can to keep us from having boots. Don’t tell me a damn thing about some bootstraps.”

Fannie Davis is filled with memorable imagery that evokes the energy of Davis’s life. That house was a New England-style colonial with three floors, a backyard, and sparkling new appliances—a home that let young Bridgett dream. It was filled with people, night and day, and Fannie was the engine that powered it all: “an ever-present life force,” Davis writes.

Davis now understands the risks of her mother’s business in a way she never did as a child, and she sees her mother as all the more heroic for it. Fannie risked everything to create something denied to black families through targeted discrimination: generational wealth. The World According to Fannie Davis is an inspiring tale of love, loyalty, and prosperity against all odds.

Erica Ciccarone is the culture editor for the Nashville Scene. She holds an M.F.A. from the New School and is writing a novel.