Unraveling a Mystery

Poet Kate Daniels explores addiction as a family illness

In her latest collection, In the Months of My Son’s Recovery, poet Kate Daniels surveys the difficult terrain of addiction, an affliction that seems as old as humankind, yet keeps baffling us anew. Daniels, who has published four previous collections of critically acclaimed poetry, writes from her own experience with substance abuse—not as an addict but as someone profoundly affected by a family member’s addiction.

Though the woman who speaks through these poems is not Daniels herself, she confronts the same dilemma Daniels knows: how do you help your loved one without being drawn into the destructive maelstrom of his illness? At the same time, Daniels’s narrator navigates the inevitable changes in her own life wrought by the passage of time.

Though the woman who speaks through these poems is not Daniels herself, she confronts the same dilemma Daniels knows: how do you help your loved one without being drawn into the destructive maelstrom of his illness? At the same time, Daniels’s narrator navigates the inevitable changes in her own life wrought by the passage of time.

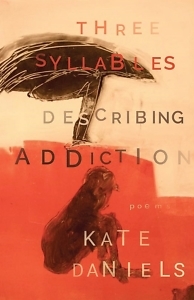

A selection of poems from In the Months of My Son’s Recovery has been issued by Bull City Press as Three Syllables Describing Addiction, a chapbook that includes the “Twelve Steps” familiar from Alcoholics Anonymous and other recovery programs. Daniels, who is the Edwin Mims Professor of English and Director of Creative Writing at Vanderbilt University, conducts “Writing for Recovery” community workshops in Nashville and elsewhere. She answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: In the Months of My Son’s Recovery is focused on a mother’s experience of her child’s addiction, but it’s also a collection about aging and trying to make some peace with life’s inevitable losses. Can you comment on how those two subjects intersect in your conception of the book?

Kate Daniels: At the most general level, I guess that both of those subjects are about loss, aren’t they? Aging, of course, as you say. But addiction, as well. Even if your addicted loved one doesn’t die from the affliction, or disappear from your life, there is always loss involved: loss of trust, loss of hopes for the future, loss of promise and potential, loss of health, loss of relationship, loss of the emotional intimacy of loving and caring for someone in mutual ways. Addiction kills mutuality by taking people away from themselves, as well as separating them from those who love them. It’s a cycle of escape, loss, and denial over and over again, it seems to me.

Getting older, of course, seems to be almost totally about loss: physical breakdown, mental decline, the death of friends and family, loss of earlier identities that we might have worked hard to acquire and are reluctant to shed. Like most people, I find aging to be harrowing, but it’s also kind of engrossing. It is both the most predictable, clichéd thing and also brand new. Your whole life you’ve been climbing a mountain, moving towards a distant goal. (At least that’s what life until age sixty was like for me.) Maybe you noticed when you actually got to the summit, but I think a lot of people get so busy they don’t notice, and then all of a sudden, the climb is over, and they’re on the way down! “Because I could not stop for Death,” as Emily Dickinson put it, “He kindly stopped for me – / The carriage held but just ourselves / And Immortality.”

Perhaps it is weird, but I find this new perspective fascinating in all kinds of ways. Sometimes I think I have been a little old lady since about age five, preparing for this my whole life. On the one hand, aging seems sort of cozy and inviting—lots of tea drinking and reading nonstop, and (once I retire in four years) not having to be so responsible to others and having my time taken up by the university. As a woman, it’s a huge relief to be no longer in the grip of the mating game, and to no longer feel defined by how “attractive” I feel myself to be based on the external standards of other people’s opinions.

On the other hand, the disappearance through death or dementia of people you love is just plain awful. No way around that. People keep disappearing. The roll call keeps getting shorter and shorter. I often have the sense that my posse or my pack—whatever you want to call it: the loved ones I have spent my life with, as well as those who could be called fellow travelers (for me that’s my generation of poets, and the generation of writers immediately ahead of us)—is getting smaller and leaner month by month, and that the process is non-negotiable and relentless and can’t be reversed or improved in any way.

Truly, that sucks. On the other hand, I continue to be fascinated by emotional resilience and spiritual stoicism. How do human beings get through what we have to get through? Why do some people face the challenge directly, and others don’t seem to be up to the task, or robust enough? My baby brother died at forty-nine years old of severe alcoholism. Why was it that way for him? Why couldn’t he make it through? What was that all about? Twelve-step recovery sees alcoholism and addiction as a spiritual illness that manifests physically in the organic form of the brain chemistry of addiction and all the life destruction that follows from that. Treatment requires medical and spiritual and psychological interventions. I totally agree.

I see addiction of any sort as an attempt to protect the self from feeling pain—even though that just seems to me to be the magical thinking of a child. Sadly, my family of origin is full of people lost to addictions of various kinds who weren’t able to muster enough resources to endure the bottom-line hard fact: living is not just about being “happy,” or “having fun.” Anyone who really believes that is surely going to be disappointed if that’s their goal in life. For some, alcohol and drugs seem to temporarily take away the feelings of discomfort that everyone experiences and places them in a “happy place.” Some people just seem to need that more than others. Who knows why? I try to let it alone. Otherwise, I’d eat my brain up wondering about it.

Chapter 16: Addiction is the subject of a tremendous amount of social, medical, and political discourse. Was it ever difficult to find your own voice in all the chatter?

Chapter 16: Addiction is the subject of a tremendous amount of social, medical, and political discourse. Was it ever difficult to find your own voice in all the chatter?

Daniels: What an interesting question! I hadn’t thought about that until now. Thank you for asking it. You’re right: lots of “chatter” in different forms about the opioid epidemic at present. For me, the main “texts” were my inner dialogue (which was so terrifying I mostly switched it off when I could), what I heard at the twelve-step meetings I constantly attended, and what I was reading about in the media and educational materials relating to addiction. All of those ultimately fed the poems when I was finally able to write them after about two years.

I don’t think I ever felt a sense of conflict between those different sources. Because I’m a narrative poet, I’m used to incorporating information into poems and accessing different sources: my own, first person voice is as important in my poems as researched facts, or the narratives of other characters. Writing is like breathing to me. I write something every day—not always poems, but always I am writing to hear myself, to find myself, to make contact with myself.

Faced with this life situation which was so profoundly painful and mentally deranging, I don’t think I would have been able to speak at all if I hadn’t processed it by writing the poems, reading poems others have written on the subject, and sharing my thoughts aloud with people in similar situations, both in writing workshops and in twelve-step groups. I also immediately went back into psychotherapy. So that was another clamoring voice in the discourse, I guess.

So, yes: it was hard, definitely, to begin to write about it. And I couldn’t write about it for a couple of years. I did record some things in my journal, but for a long while, I was so frightened when I saw what would dribble out on the page, so physically affected, that I would start to shake and cry. I really couldn’t bear what I knew unconsciously about how dire the situation was. For a long time, I just had to stay in the moment, and keep breathing and eating and sleeping and driving and teaching my students. It took a lot of work, and a lot of time, before I could bear up beneath the weight of the subject matter and actually begin to write the poems.

Chapter 16: The Bull City Press collection, Three Syllables Describing Addiction, is drawn from the poems in the L.S.U. collection that are focused on addiction. Did you always envision those poems as a unified collection? How did that book project come about?

Daniels: Three Syllables Describing Addiction is a chapbook collection—short, just sixteen poems, I think. It came about after the entire book manuscript had already been accepted. I had begun teaching Writing for Recovery workshops for The Porch (which I am still doing) and also outside of Nashville as I was traveling about, giving readings. It occurred to me that it would be helpful when I was working with groups whose first interest was in recovery (rather than with people who primarily identified as writers) if there was a shorter collection available, entirely focused on recovery. Bull City Press was interested and willing to put it out right away, before the full-length book. And L.S.U. was kind enough to give permission. So that’s how that happened.

Can I give a plug here for a writing and recovery workshop I’m teaching at the end of June at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, on Cape Cod? I’d love to have some fellow Tennesseans enrolled. It’s a great place to spend a week, writing with a whole group of writers and artists, and an escape from Tennessee heat! By the way, the piece on the cover of Three Syllables is by Robert Henry, who lives on Cape Cod, and teaches at the Fine Arts Work Center. That’s how I discovered him. I think he is an extraordinary artist.

Chapter 16: I doubt there’s a woman over fifty who wouldn’t see a bit of herself in “Her Barbaric Yawp,” which evokes post-menopausal womanhood in all its sorrows and contradictions. Can you tell us about the genesis of that poem and why you chose to open the collection with it?

Daniels: The genesis of that poem was/is something very quirky—and maybe kind of gross—that has stuck in my mind for decades. When I was a rising senior at the University of Virginia in the 1970s, three friends and I went to look at an off-campus apartment we wanted to rent for the upcoming year. It was on the top floor of a wonderful old house. It had four big bedrooms, and when I went into the one that I wanted—a corner room with windows on two walls and a high ceiling—I could tell that it was inhabited by a woman I would like to know, and with whom I immediately felt solidarity.

I knew her name was Gretchen, and I could see that she wore cowboy boots and hot pants. Reading the “text” of her belongings, and the messy condition of the room that was also strewn with body lotions and hair brushes, and seeing a shelf of books from what was then the hot center of what we now call second-wave feminism (back then we just called it women’s lib), I identified with her. Her belongings suggested we were both fighting the same fight.

That feeling changed to astonishment when I almost stepped on a diaphragm thrown casually in a corner, all gummy and gray and unwashed! Up until that point, I had thought I was a pretty decently liberated woman of that era, but when I saw that I was so shaken by the sight that I realized all at once that I had a really, really long way to go in achieving personal freedom from socially-imposed ideas about gender-appropriate behavior!

I thought I was “liberated” because I felt free (enough) to have sex outside of marriage and use birth control. I, too, used a diaphragm but in a very different, almost clandestine way. Keeping it secreted in its little plastic clam until the very last moment and drawing it out of the bedside-table drawer at the last moment in the dark. And surreptitiously washing and drying and powdering it as soon as the directions said enough time had passed to make it effective. That was what being a women’s libber meant to me at twenty years old in 1973. So when I saw the completely unselfconscious freedom of Gretchen, I was sort of shattered apart in a good way.

That little dramatic moment—looking at a room I wanted to move into, to occupy, and feeling first a sense of solidarity with its inhabitant, and then shocked into a new awareness of the diversity of what women’s liberation could look like—stayed with me for almost four decades. It jolted me forward. That autobiographical moment is literally where the poem originated.

As for opening the book with it, I decided that the focus in the book overall had to be on the female main character of the title, In the Months of My Son’s Recovery, rather than on the character of the son. The book is, after all, a story of recovery from the collateral damage of a loved one’s addiction, not a story of alcohol or drug addiction itself. (As for instance would be some of the poems of writers like Kavah Akbar or Sheryl St. Germain or Nick Flynn.) At first I thought the whole book would be poems on addiction and recovery. But at some point, I had the thought that I wanted the main character of the woman to be established as a character in her own right before we see her struck down by the addiction in her family. I wanted her to be established as a person/character in her own right before her “problem” was introduced.

The original manuscript had another poem that L.S.U. would not let me use called “She Poets Cento.” It’s a long quilt poem made from one-liners from poems by seventy-nine women poets whose work has been important to me. It’s a very feisty and feminist poem, and I thought it went well with “Yawp.” But L.S.U. is very strict about fair use of poetry—even one-liners with attributions!—so even though the poem had been published in John Hoppenthaler’s A Poetry Congeries, they wouldn’t let it in the book.

And I regret that because one of the major concerns of my poetry across the years has been gender, the female gender, and in particular the necessity of women’s solidarity. I wrote that poem as an act of homage to all the women poets who have been important to me. When L.S.U. wouldn’t let me use it, I put the anorexia poem in its place—another poem that is sounding off about gender issues, and I thought helped define the book’s narrative persona.

Chapter 16: I was struck by “Epiphany in the Atheist’s Kitchen.” It’s raw reporting from the frontline of spiritual experience. There are also epigraphs in the collection from theologian Thomas Merton and from John Berryman, a deeply spiritual poet tormented by addiction. How is your work shaped by your own spiritual concerns?

Chapter 16: I was struck by “Epiphany in the Atheist’s Kitchen.” It’s raw reporting from the frontline of spiritual experience. There are also epigraphs in the collection from theologian Thomas Merton and from John Berryman, a deeply spiritual poet tormented by addiction. How is your work shaped by your own spiritual concerns?

Daniels: My spiritual concerns, and my religious beliefs as an adult convert to Catholicism, are always at the center of my poetry, and my life. I was born with the gift of faith, and it has stayed with me. Who knows why? I try not to spend too much mental energy wondering about the mystery of that… I do think that my apparently unshakeable belief in the meaningfulness of our human life, and my conviction that there is a benevolent divinity at the starting point of it all, naturally inclined me to be able to make use of twelve-step programs—although that is the very thing that can be a stumbling block for a lot of people. But I had no trouble accepting the notion of a Higher Power, and how to make explicit use of that in the context of a loved one’s addiction that was so painful I thought I would expire from the suffering. My faith, my friends, and twelve-step were the things that pulled me through.

Chapter 16: You make it clear that the narrator in these poems is “similar, but not identical, to myself,” and yet the material here is deeply personal for you. What are your guideposts for the process of rendering personal experience into art?

Daniels: I understood from the time I was in my twenties when I began to be deadly serious about writing and publishing poetry that I was writing out of autobiography (my “muse,” if you want to think of it that way), and that my frame of reference and my compass point was the family. My family. First, my family of origin, and then the family I made through marriage and motherhood. I have certainly written poems that have been painful for various members of my family, and I regret that they were pained. But I have never written to “get back” at anyone, or in a vengeful mode. (Those things are reserved for my therapist’s office!)

While I have never written to humiliate or expose anyone in my family, I try to give myself unlimited permission and as much freedom as possible to write whatever comes up at the start of the process. But once I have a decent draft, I always interrogate myself about whether what I am writing about belongs to me, or not. If it belongs to me, I can go ahead. If I am appropriating someone else’s experience for my own ends, I can’t go ahead. I won’t. As egotistical as it sounds, I’m always writing about myself and my experience even though my subject matter is so often my family, and even though my poems are peopled with characters from my family.

I write to try to unravel some kind of mystery at the heart of familial relations and the extraordinarily powerful ties of human relatedness, and the deep crevices and kinks and twists and turns of the human psyche. In my opinion, poetry just can’t be used for bad purposes—it just turns into versified propaganda if you do that, the antithesis of poetry.

For this particular book, the material was not just “hot” for me, but for the members of my family who were similarly affected by the situation. Before I sent the manuscript off, I circulated it to my immediate family members and invited them to ask for changes, request deletions, etc. There were a few small requests, but that was all. I am grateful for their willingness to have themselves represented, even if obliquely and anonymously, in the poems. Addiction is after all, the “family illness,” so it’s their story as much as mine.

[To read an excerpt from In the Months of My Son’s Recovery, click here.]

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. Her work has appeared in Guernica, Still, Hippocampus, and The Los Angeles Review of Books. She’s the managing editor of Chapter 16.