A Boy and His Hero

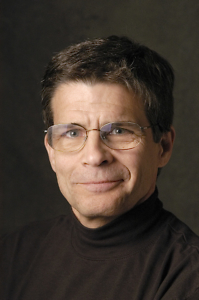

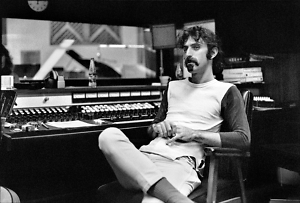

Bill Gubbins recalls an extraordinary 1969 encounter with Frank Zappa

In the summer of 1969, 19-year-old Bill Gubbins aspired to interview his musical hero, Frank Zappa, then touring with The Mothers of Invention in Warrensville Heights, Ohio. What Gubbins didn’t know was that Zappa would soon dissolve The Mothers and enter the studio to record Hot Rats, an iconic solo album. The Hot Rats Book tells the story of how Gubbins — who would go on to edit Creem and Country Weekly — not only interviewed Zappa but was invited to photograph the Hot Rats recording session and camp out in Frank Zappa’s Los Angeles home. Gubbins’ photos and narrative offer a unique insight into a legendary musician, as well as a fascinating personal story of a teenage dream fulfilled.

Gubbins, who lives in Nashville, recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Gubbins, who lives in Nashville, recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: What a remarkable story The Hot Rats Book tells — not just for Zappa fans, but for anyone who was once a teen in small-town USA with a hero and a crazy hope/desire to spend time with him or her. What inspired you to create this particular book now?

Bill Gubbins: First, thank you, for your kind words about the book. Here’s the genesis of the project:

The Hot Rats shots were in storage from 1969 to 2014. In the fall of 2014 I dug them out, took them to Chromatics, the great Nashville photo house, had them scanned, then used them to create a book prototype entitled August 1969 (An intimate look at the recording of Hot Rats).

I shopped it around for a couple of years to which I received a resounding chorus of rejections, and pretty much put it on the back burner.

In the fall of 2017, I was so impressed with Meat Light (the reissue of Frank’s 1969 Uncle Meat) that I sent a fan note to Joe Travers, the project’s producer. To my surprise, Joe answered the email, and I mentioned the book [and] sent him the prototype. He forwarded it to Ahmet Zappa, Frank’s second son and head of the Zappa Trust. Ahmet liked it; we then met in March of 2018, and in the fall of ’18 formed a partnership to publish the book on the 50th anniversary of the release of Hot Rats in October of ’69.

And there you have it.

Chapter 16: You touch on this in the book, but what was your fascination with Frank Zappa’s music in your teens? And has that evolved over the years?

Gubbins: I still love Frank’s music as much as I ever did, if not more. I mean Hot Rats was recorded 50 years ago and it sounds like it was recorded 50 minutes ago.

I think Frank’s core appeal was the sheer totality of his singularity — there wasn’t anyone similar who preceded him and there certainly hasn’t been anyone even close since. I think the only way to approach Frank’s body of work (which is not limited to music, by the way) is to consider him an artist, rather than a “composer” or another music-related term.

And, as an artist, the most useful analogy is probably Pablo Picasso, who, like Frank, succeeded in multiple mediums, was both breathtakingly prolific and extraordinarily innovative, and whose final work was qualitatively equal to his early work.

Chapter 16: The structure of the book, with Ahmet Zappa interviewing you, is novel and effective. Who suggested that structure, and why was it chosen? How did the interview develop?

Gubbins: The first version of the book was too broad — and pretty prose-heavy — so we decided to narrow it down. It was then I recalled [that] one of the first things Ahmet said when we met was that he wanted to interview me for the book, and I thought a book-length interview might be a more engaging way to convey the information. Ahmet agreed, and we were off to the races.

Chapter 16: In a recent performance, Dweezil Zappa mentioned that his father never performed live the last cut on the album, “It Must Be a Camel.” That would make you perhaps the only non-musician to have heard/seen that rather curious tune performed by Frank. Have you seen Dweezil’s performance of it?

Gubbins: I didn’t see Dweezil’s Nashville show, so I can’t really comment. I did see him at Bonnaroo and thought he did a great job playing his father’s music.

Chapter 16: For photography buffs: It’s cool you give several shout-outs to your trusty Nikkormat. I noticed some of your photos were in color and some in black and white. Can you recall how you made those choices? Did you use flash at all? What film stock were you using?

Gubbins: The film-stock choice was strictly financially driven: Color film was very expensive back then so I bought as many rolls as I could afford (which wasn’t many). The stocks I used were Tri-X black and white, and Ektachrome and Kodachrome color. I was not evolved enough to use a flash and couldn’t have afforded one anyway.

Chapter 16: The Mothers in motion photo on page 27 of the book is really something. How did you get that? Was it intentional, a happy accident?

Chapter 16: The Mothers in motion photo on page 27 of the book is really something. How did you get that? Was it intentional, a happy accident?

Gubbins: I’m guessing most of the live shots were probably shot at 1/60 or 1/30 of a second but I decided to intentionally use some longer exposures (maybe 1/15, 1/8 or even 1/4) to accentuate the motion. I got lucky and they worked.

Chapter 16: Are there more photos you would wish to have included in the book but couldn’t for space/cost constraints?

Gubbins: Every shot was used so it’s pretty much one and done.

Chapter 16: Frank Zappa was influenced by an enormous range of composers and musical genres. Any thoughts on his musical legacy?

Gubbins: Not sure I’m the right guy to really do the “musical legacy” question justice, but here’s my take: I think something like 67 albums of Frank’s music have been released. For laughs, let’s say the average length of each album was 30 minutes (probably low), which means his current output is something like nearly 34 hours of music (67 albums x 30 minutes per [album] = 2,010 minutes then divided by 60 minutes per hour = 33.5 hours).

Now I haven’t listened to all 34 hours but I’m guessing I’m relatively close — and I’ll say this: It’s all interesting (in the Stanley Kubrick usage of the word) and there is no end to the breadth of music genres Frank worked in. (Frank did everything from rock to classical, from country to gospel, from electronic to jazz; heck you could even say “Trouble Every Day” from 1966 was one of the first rap songs.)

The other thing to keep in mind is that Frank’s legacy goes way beyond music, extending into disparate fields including — but not limited to — fashion, filmmaking, and philosophy.

In short: if you’re wearing a man bun or an ironic t-shirt today … thank Frank Zappa.

Jonathan Frey lives in Knoxville and writes about music and books.