The Love-Rack

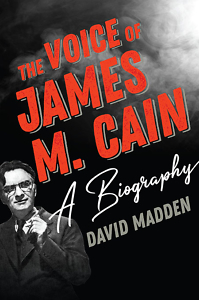

David Madden’s inventive biography details the writing life of an American noir master

David Madden describes his new book, The Voice of James M. Cain, as “innovative in style and technique.” He might have added that it’s also a love letter to his mentor, an encomium for the writer who taught Madden how to find his own voice. Neither scholarly biography nor literary monograph, Madden’s book tells the story of Cain’s life in the close third person, from his initial calling to become a writer at age 22 until his death 65 years later.

Madden knows he has a dynamite story to tell and wastes no time on the extraneous. He uses Cain’s own words whenever he can, drawing from a 125-page autobiographical manuscript that Cain sent him in the late ‘60s, and then “blends” Cain’s account with his own extrapolations. The resulting narrative successfully captures Cain’s literary persona in a moving portrait of a writer who believed his primary job was to connect with readers.

Madden uses quotation marks for material taken from Cain’s published works and personal letters but drops them when pulling from Cain’s unpublished autobiography or when inventing Cain’s voice. This process sounds confusing, but in practice it is seamless. From an essay on screenwriting, Madden quotes from Cain, “For my part, when I go to a movie, I am entertained best if it is unabashedly a movie, and not a piece of dull hoke, posing as something else.” To this sentence Madden adds, without quotation marks, “In this conclusion, he had expressed his own attitude as a fiction writer.”

Cain believed that the popularity of a work of fiction is the only valid barometer of success. In the last year of his life, a reporter asked him, “Which of your own books would you say stand up best?” Cain evinced no ambivalence. “The book that stands up for me is one that sold the most copies,” Cain said, “and that one was The Postman Always Rings Twice.”

Cain’s advice regarding Madden’s own career struck a similar, mercenary tone. “David, why this obsession with the literary?” (Cain used literary derisively.) “For Christ sake get out of the wading pool and dive off where the waves are big, the fish are big, and the money they bring is big. It’s moula that makes the world go round – not love.”

One of his early bosses in Hollywood accused Cain of making “a sort of algebraic equation” out of storytelling, a criticism that Cain took for praise. His early drafts of Postman didn’t work because Cora spends too much time in jail, so he invented the “insurance angle,” a device that “got the story moving again.” The plot thus accelerated, the “algebra” of the tragedy became clear in Cain’s mind.

“To make readers feel the impact of their encounter and consequences, Cain had Frank and Cora meet on page 5, make love on page 15, and decide to murder the Greek on page 23,” Madden writes. “This action kept in motion certain elements that almost guaranteed reader interest: illicit love, murder, tainted money, sexual violence that verged on the abnormal.” Madden’s analysis is a veritable manual for writing American noir.

Central to all of Cain’s work is the “love-rack,” a concept he borrowed from veteran screenwriter Vincent Lawrence (to whom Cain dedicated Postman). After lovers meet, “they go on the love-rack when they work together to handle a problem that often separates them, but then they are happily reunited,” Madden writes. “Watching the lovers on the love-rack makes us care about them.”

Cain felt that following this formula in no way cheapened the product. To the contrary, working within narrative strictures enabled him to bore to the heart of human experience. Some critics agreed; others were less enchanted. Madden quotes extensively from contemporary reviews, including ones that skewered Cain’s work. “The bare outlines of Mr. Cain’s plot are constantly revolting,” read one review of Serenade, Cain’s second novel, but Cain “manages to invest his most sordid details with glimpses of the human subconsciousness.” The New Yorker judged Serenade to be “beautifully crafted hokum, guaranteed to thrill.”

Cain felt that following this formula in no way cheapened the product. To the contrary, working within narrative strictures enabled him to bore to the heart of human experience. Some critics agreed; others were less enchanted. Madden quotes extensively from contemporary reviews, including ones that skewered Cain’s work. “The bare outlines of Mr. Cain’s plot are constantly revolting,” read one review of Serenade, Cain’s second novel, but Cain “manages to invest his most sordid details with glimpses of the human subconsciousness.” The New Yorker judged Serenade to be “beautifully crafted hokum, guaranteed to thrill.”

Madden stays focused on Cain’s writing, offering passing descriptions of Cain’s encounters with dozens of figures in journalism, literature, and Hollywood. His newspaper mentors were H.L. Mencken and Walter Lippmann. Cain worked briefly for Harold Ross at The New Yorker, editing E.B. and Katharine White and James Thurber. He drank with Theodore Dreiser, Sinclair Lewis, and Willa Cather and had a disappointing lunch with F. Scott Fitzgerald. The only figure from the era Cain didn’t meet was Ernest Hemingway, the writer to whom he was most often compared.

Madden, a native Tennessean and distinguished writer of fiction and non-fiction, does not hide Cain’s disagreeable traits (sexism, racism, a touch of pedophilia), nor does he belabor them. In Madden’s hands, Cain re-emerges as a master of form, a craftsman who labored on behalf of his readers. “Whether he is enticed by the prospect of sex, riches, violence, or whatever,” Cain said, “the reader must be indulged.”

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.