Why Merle Haggard Deserves a Nobel Prize

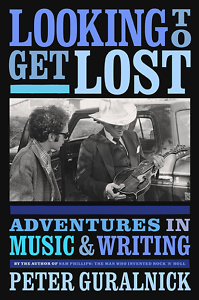

Peter Guralnick discusses his latest book, Looking to Get Lost

If Peter Guralnick only accomplished rescuing Elvis Presley from the bilious clutches of notorious biographer Albert Goldman, he would have done plenty for American culture.

But he’s achieved far more than his epic two-volume biography of Presley, which remains the definitive text on the king of rock and roll nearly three decades after publication. He followed up the Presley books with critically acclaimed biographies of singer Sam Cooke and Sun Records producer Sam Phillips. His earlier portraits of blues, country, soul, and rock and roll singers are often the final word on the careers of American musicians both famous and overlooked.

In a wide-ranging interview with Chapter 16, Guralnick talked about his latest book Looking to Get Lost: Adventures in Music and Writing, a return to the short-profile format of his earlier efforts. This one has a lengthy piece on overlooked country crooner and trucker-singer Dick Curless, illustrating how Curless’ service in the Korean War haunted him for the rest of his life. Another entry reveals Guralnick’s decades-long relationship with soul singer Solomon Burke, who tended to be a bit of a confidence man. Guralnick nearly got caught up in one of the schemes. Other profiles include Tammy Wynette, Ray Charles, Chuck Berry, Delbert McClinton, and a dual profile of Elvis Costello and Allen Toussaint as they worked together on an album.

Guralnick taught creative writing at Vanderbilt University from 2005-2016, where I enjoyed sporadic conversations with him at the Starbucks near campus about writing, teaching, and music.

The transcript of our recent conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Chapter 16: You picked a somewhat obscure subject for the centerpiece of Looking to Get Lost: Dick Curless, probably best known for his eyepatch and 1965 hit “A Tombstone Every Mile.” Is it different or more difficult profiling someone less famous?

Peter Guralnick: I don’t think I approach it any differently. I don’t mean to be arrogant, but I have to make the assumption that if I’m interested enough and I put enough of myself into the story, then other people will be interested too. That may prove to be a poor strategy in the end, but I don’t know any other way to do it. It was never a question of seeking out people who had fame beyond a certain point. It didn’t matter if they had fame at all. Stoney Edwards was barely known. DeFord Bailey when I met him was living in a retirement home. Sure, it was a name that evoked a certain amount of recognition from people who remember he played the first notes on the Grand Ole Opry, but otherwise knowledge about him was not that great.

Chapter 16: What was it about Curless that attracted you?

Guralnick: It certainly is the longest profile I’ve ever written. It’s almost like a nonfiction novella. I thought of it as a way of telling an extraordinary story about someone [who] might appear to be an ordinary man, but who had such depth and complexity. I wanted to get that across. … When I went up to Bangor, [Maine], and spent two or three days talking to him, he was so insistent on the truth. You can’t write a story that just skims the surface. You have to tell the truth. Life is hard sometimes. It was so important to get that across, so for me it was emotionally difficult to write it sometimes. Not as difficult as it was for him to live it. It wasn’t the story I wanted to write, yet it was the story I felt I had to write.

Chapter 16: The chapter on Solomon Burke is a riot. The reporting was done over a period of decades, right?

Chapter 16: The chapter on Solomon Burke is a riot. The reporting was done over a period of decades, right?

Guralnick: I had written so much about Solomon over the years, but this was a different way of approaching it. I was trying to approach it in a way that was truthful to the experience not just of his life, but also of our interconnection, which was so important to me. The thing I wanted to get across was that there was nothing that could be more fun than being with Solomon Burke. With one day with Solomon Burke you could make three movies. It was like a circus with nine rings or something.

Chapter 16: You and Burke hoped to do a whole book on him at one time, right?

Guralnick: In trying to get him to do the book, you just couldn’t nail him down. You couldn’t say, “Look I’m going to come out on this date. You be there and we’re going to work from 9-12 and 3-6 every day.” That just wasn’t Solomon.

Chapter 16: In your piece on Johnny Cash, he rages against the injustice of older singers like Hank Snow being pushed aside. But it’s ironic that it was about the time Cash himself was going through that experience.

Guralnick: It was right at that time, really. I felt like what was so interesting with Johnny Cash was that a person with such self-knowledge would in a sense deflect some of his concerns about himself, which is the overriding concern of all of us as we get older. It served as a kind of metaphor for both his self-knowledge on the one hand, and on the other hand the way he dealt with it. He dealt with it by putting it off on another generation. He was struggling right at that time or immediately afterward by having been dropped by Columbia. … At the end of his life doing those recordings with Rick Rubin [at American Recordings] seemed to satisfy his thirst for creative adventure, which never stopped.

Chapter 16: You quote other writers’ work in your stories, crediting them of course. Does it bother you? Do you wish you had gotten those quotes and that information yourself?

Guralnick: Not at all. I’m very aware of other people’s contributions. This would be like denying that we’re standing on the shoulders of giants. I hope that I credit these sources sufficiently. … For instance, Cliff White, the English rock writer, was a wonderful guy and a wonderful writer. To quote him quoting Jerry Lee [Lewis], to me that’s finding some of the best things that have been written about the artist. And then I hope to take it further.

Chapter 16: You’ve had some disappointments with profiles or biographies you would have liked to write. Which one do you regret the most?

Guralnick: I missed out on Merle Haggard. His manager, Tex Whitson, remains a friend to this day and was a great advocate for me. Tex and Merle and I made plans to go to Bakersfield, [California], together. I don’t know if I was thinking of a book, because I hadn’t done any biographies at that point. I just thought this will be a great adventure and a great opportunity and a great thing to do. And then Merle backed out at the last minute, which was not uncommon. That would have been fantastic. … Merle was such a moody person. Temperamental. A genius. Just an amazing talent and a person of great depth.

[Editor’s note: Although a Guralnick book on Haggard never happened, there is a profile of him in Looking to Get Lost.]

Chapter 16: One Looking to Get Lost reviewer scoffed at your contention that Haggard should be considered for a Nobel Prize in Literature, which Bob Dylan won in 2016. Would you make your case for him?

Guralnick: If we’re going to give songwriters Nobel Prizes in Literature, then people like Chuck Berry or Merle deserve consideration as much as any other songwriter because of the genius in their work. … I don’t think there has been anyone who has sustained the kind of length and depth of creativity that Merle showed as a songwriter. My point fundamentally is that these people should not be consigned to categories. They shouldn’t be shunted off to the corner. Merle’s work and Merle’s songwriting are as serious as you’re ever going to find. The breadth of it is astonishing.

Chapter 16: There are profiles of novelists Lee Smith and Henry Green included in the new book. Do you wish you had done more of this kind of thing?

Guralnick: I would have loved to profile more writers. I think that would have been fascinating. … I wrote a piece about Zora Neale Hurston which I thought about keeping in this book. I wrote it on the occasion of the Robert Hemenway (1980) biography, which is terrific. Most of her work was out of print at that point. I did the same thing with Mark Harris, who is best known for Bang the Drum Slowly. I met him after that and I tried to sell the idea of doing a profile of him, because he was another writer that I very much admired. But I just never could get anyone interested.

Chapter 16: Your first book was short stories and you also published a novel, [Nighthawk Blues], some years ago. Are you still pursuing fiction?

Guralnick: I’ve been writing these short stories for years. I’ve got 12 or 13 now. I’m hoping to put them together and be able to publish a selection of them. … I’ve approached people both in publishing and agents who I would say if I came to them and said, “I want to do volume three of my Elvis biography or I want to do a book on the Rolling Stones or Bob Dylan or something,” I would get a wonderful reception. These same people, I never heard back from, or I barely heard back from them if I heard back from them at all about the short stories. … I finally ran into a publisher who has indicated interest and I think might follow through, which would be very exciting to me.

Chapter 16: What else do you have on the horizon?

Guralnick: I’ve started now on a project that initially I wanted to start 20 years ago, which was a collection of Colonel Parker’s letters, which I would select and annotate and introduce. That’s actually becoming a reality. So I’ve actually got three books that I’m moving toward.

Chapter 16: What’s the third project?

Guralnick: The third is yet to be named. I’ve decided I have to keep certain things to myself. But there is a third book, which I have had considerable interest in and would like to do.

Jim Patterson is a freelance writer in Nashville. His work appears regularly on the United Methodist News website, UM News. He formerly covered country music for the Associated Press and was a public affairs officer and senior writer at Vanderbilt University.