Magic, Madness, Mystery, Magnificence

W. Ralph Eubanks explores the literary tradition in Mississippi

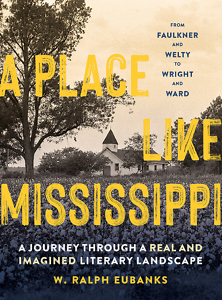

For a state with relatively few people, Mississippi has produced some of the greatest artists and writers in American history. In A Place Like Mississippi, W. Ralph Eubanks explores the literary culture of the Magnolia State in all its charms, oppressions, and contradictions. While touring with his readers from the Gulf Coast to the Hill Country to the Delta, Eubanks considers what Mississippi means to our collective imagination.

Eubanks is a visiting professor of English and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi. He is a former editor of the Virginia Quarterly Review, director of publishing at the U.S. Library of Congress, and a Guggenheim Fellow. His previous books include Ever Is a Long Time and The House at the End of the Road. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Eubanks is a visiting professor of English and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi. He is a former editor of the Virginia Quarterly Review, director of publishing at the U.S. Library of Congress, and a Guggenheim Fellow. His previous books include Ever Is a Long Time and The House at the End of the Road. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: You state that, whether a writer stays or leaves Mississippi, “the urge to explain it and understand it never leaves your consciousness.” Why? As someone who was born in Mount Olive, left the state for much of your adult life, and has since returned, how have you grappled with the meaning of Mississippi?

W. Ralph Eubanks: Mississippi looms large in the American imagination, and even in the world. From the moment I left — which at the age of 20 felt more like an escape — I have been explaining Mississippi to everyone I meet, almost like the Ancient Mariner telling his tale of woe to everyone he encounters. And given Mississippi’s history, which is marked by racial violence and oppression as well as great art, the duty of explaining the place has fallen to our writers. What surprised me in those years after I left is that I did not find myself explaining Mississippi as much as defending it.

For a long time, I resisted the siren call of the South. My focus in graduate school at the University of Michigan was on Victorian and modern British fiction, even though Faulkner’s biographer, Joseph Blotner, taught at Michigan. In middle age, I came to the realization that Mississippi can never be escaped. When you are from a place that constantly brings up questions, there comes a time when you begin to feel as if you have to begin to answer those questions, rather than evade them. And confronting some of those questions is part of this book.

Chapter 16: A Place Like Mississippi is a gorgeous book, filled with photographs of the landscape and from history. Did you always conceive of the book as marrying text and images in this way? What role do the images play, in your mind?

Eubanks: Yes, photography was always part of the idea of this book. The desire to represent reality, beauty, and truth at the same time remains one of the great tensions in the art of photography. I feel those same tensions as a writer, and by pairing my words with photographs, I hoped readers would be drawn into A Place Like Mississippi. And there are some amazing photographs of Mississippi (particularly the Farm Security Administration photographs taken during the Great Depression), since the South is one of the most documented regions of the country. Photographers are drawn to the South because of its perceived authenticity as a place geographically and culturally distinct from the rest of the country.

One of my favorite books is Geoff Dyer’s The Ongoing Moment, which is a meditation on the power of photography. Dyer argues that many writers are unconscious photographers, and I guess I am also one of those writers obsessed with the visual. Although I think in words, I also imagine how those words create an image.

Chapter 16: When meditating on William Faulkner’s estate in Oxford, you write, “It’s hard to look at the white columns of Rowan Oak without thinking of the way memory casts its shadow on the landscape of this little town.” Does that idea apply throughout the state? In Mississippi, it seems, the past and present are always in conversation.

Chapter 16: When meditating on William Faulkner’s estate in Oxford, you write, “It’s hard to look at the white columns of Rowan Oak without thinking of the way memory casts its shadow on the landscape of this little town.” Does that idea apply throughout the state? In Mississippi, it seems, the past and present are always in conversation.

Eubanks: I always say that when you find where the past and the present intersect in Mississippi, you can understand the world. In Mississippi, history and memory loom large on the landscape of nearly every corner of the state, whether it is at Faulkner’s Rowan Oak, with its connections to a great literary figure and the shadow of slavery that looms on those grounds, or the banks of the Tallahatchie River, where Emmett Till’s body was found. Since there are so many stories that have been silenced, there are many places where memory casts its shadow that are not immediately apparent. One of the things that makes Mississippi a unique place is the way the landscape pairs ordinariness with beauty, magic with madness, and mystery with magnificence.

Chapter 16: Mississippi is notorious for its history of racial oppression. Is its literary tradition segregated? How do you think about writers like Faulkner and Eudora Welty in relation to authors such as Jesmyn Ward, Natasha Trethewey, and Kiese Laymon?

Eubanks: Whether consciously or unconsciously, scholars long examined Mississippi’s literary tradition through a segregated lens. Unfortunately, the Magnolia State’s racial binary affected the way it framed its literature, placing Richard Wright and Eudora Welty in separate spheres, even though they grew up in the same town. Without question, there is a big gap between the world of Wright’s Black Boy and Welty’s One Writer’s Beginnings. But that reveals the complicated nature of Mississippi: two people can experience the same place in radically different ways. What I hope I have done in the pages of this book is to reveal the intimate connections among all these writers. Ward, Trethewey, and Laymon see themselves as part of Mississippi’s literary tradition, not just one segment of it.

Chapter 16: One abiding theme in the book is that writers take risks — they challenge the accepted way of thinking about things. What does that mean for someone in Mississippi today with literary ambitions? What are the opportunities and challenges?

Eubanks: Recently, C.T. Salazar, a poet who lives in the Mississippi town of Columbus, reminded me that much of Mississippi’s “traditional” literature is steeped in untangling the past. In one of his poems, he writes “Mississippi burns you last if it loves you,” a stinging line that evokes both the present and the past. He wondered if there was viable space for Mississippians writing about the future. It wasn’t until Salazar asked me that question that I realized that my generation had to explain Mississippi and its past.

Perhaps it is the job of the next generation of writers to imagine a future for Mississippi that is not tightly defined by its past. Defining and imagining that future is the opportunity and challenge for Mississippi’s next generation of writers. As a teacher, I have encountered a few of those writers and I think they are up to the challenge.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.