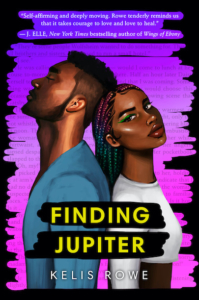

A Planet and Stars Align for Memphis Teens in Love

Former Memphian sets debut novel in her hometown

Kelis Rowe says she was on a mission to “give young readers a story about Black teens falling in love” when she wrote her debut novel Finding Jupiter, set in Memphis. In a video on her website, Rowe says her story specifically focuses on young people “living while Black and not experiencing Black trauma.”

There is, however, loss and long-lasting grief in the families of the novel’s young lovers. Ray is a rising senior who attends a girls’ boarding school in Rhode Island and otherwise lives with her mother in the Memphis neighborhood of Whitehaven. When a visiting friend raises an eyebrow about the name, Ray says, “Ironically, Whitehaven is a very Black neighborhood now.”

There is, however, loss and long-lasting grief in the families of the novel’s young lovers. Ray is a rising senior who attends a girls’ boarding school in Rhode Island and otherwise lives with her mother in the Memphis neighborhood of Whitehaven. When a visiting friend raises an eyebrow about the name, Ray says, “Ironically, Whitehaven is a very Black neighborhood now.”

Ray lost her father in a traffic accident the day she was born, though her mother will share few details about the tragedy. On her 17th birthday, Ray passes on her mother’s invitation to visit her father’s grave, and instead takes her visitor, her roommate from school, to the Crystal Palace, the now-closed skating rink in South Memphis that was once a neighborhood standard, featured in the 2005 Oscar-winning film Hustle & Flow. (The friend’s visit supplies a motive to touch down at other highlights of Memphis tourism, including Beale Street, the National Civil Rights Museum, and Elvis Presley’s Graceland mansion.)

At the skating rink, Ray, whose given first name is Jupiter, meets Orion, a competitive swimmer who will be a freshman at Howard University in the fall. Ray and Orion alternate as narrators of the book’s chapters, a romantic duet of sensitive reactions to subtle cues. When Orion makes an unannounced stop at the coffee shop where Ray works, she’s already thinking of him: “The boy in my head is standing near the entrance of the gift shop.” A minute later, she tells him not to think too much about her. “Orion’s arms tense up and he looks pensive and a little … amused?”

Orion, an athlete and heartthrob with an endearing soft side, has two cats and tears up easily. Like Ray, he’s lost a family member — his three-year-old sister — in a tragic accident. The emotional fallout from that calamity leads to a tenuous relationship with his father: “Even when he’s saying he’s proud of me or he loves me or whatever, there’s a but lingering behind his words.”

Orion, an athlete and heartthrob with an endearing soft side, has two cats and tears up easily. Like Ray, he’s lost a family member — his three-year-old sister — in a tragic accident. The emotional fallout from that calamity leads to a tenuous relationship with his father: “Even when he’s saying he’s proud of me or he loves me or whatever, there’s a but lingering behind his words.”

As the story unfolds, the loss of one father and the estrangement of the other provides more than just a psychological link for the teenaged lovers.

On the opening page, Rowe devises a poem about missing “the paternal,” using words from The Great Gatsby. In an author’s note, Rowe says her story developed when she decided to use some of her favorite books to make her character Ray a creator of found poetry. “I tabbed the moments in each book that marked the height of emotion for the main characters — where the language is the most expressive — and got to work finding poems,” Rowe writes. Whole pages of Gatsby, which is in the public domain, are recreated in Jupiter. In Rowe’s novel, a page from Gatsby that includes the words, “I was poor and she was tired of waiting for me. It was a terrible mistake, but in her heart she never loved any one except me!” becomes “I was tired of waiting for a loved one.” A page from Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God is redacted to “The boy was too good to be true.”

Rowe, who grew up in the Whitehaven neighborhood of Memphis her character Ray inhabits, now lives in Austin, Texas, but has announced that her next book will revisit the same territory as her first, the world of teens living while Black in Memphis.

Formerly the books editor at The Commercial Appeal in Memphis, Peggy Burch writes for The Daily Memphian, where she was arts and culture editor. A member of the Humanities Tennessee Board of Directors, she holds a master’s degree in English literature from the University of Mississippi.