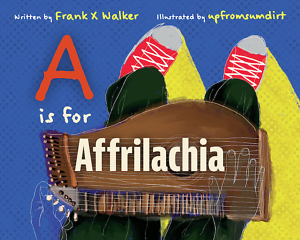

Affrilachia from A to Z

Frank X Walker’s new picture book pays tribute to Black life in Appalachia

Black luminaries, Black history, and the geographic, spiritual, and emotional spaces that hold resonance for Black people in Appalachia: These are the elements of Frank X Walker’s A Is for Affrilachia. This alphabet picture book, at more than 60 pages, is for readers of all ages.

Walker, the first African American writer to be named Kentucky Poet Laureate, coined the term “Affrilachia.” As explained in a glossary that closes the book, Affrilachia is not a place on a map. It is the “spiritual and emotional home for everyone left out of the definition of Appalachia that required whiteness as a prerequisite for membership.”

As a founding member of the grassroots organization of writers called Affrilachian Poets, launched in 1991 at the University of Kentucky Martin Luther King Center, Walker does much more here than pay tribute to Affrilachia. He celebrates the people, places, and ideas that inhabit it, and at the same time he indicts the forces of white supremacy that have tried to destroy it.

Structured as a classic alphabet book, A Is for Affrilachia takes readers from A to Z, some pages more text-heavy than others. “A,” for instance, is not just for “Affrilachia, Alabama, Asheville, and Alcoa, Tennessee”; it’s also for “Addie Mae Collins — one of the four little girls killed in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church.” In addition, “A” is for writers Angela Davis and August Wilson, who wrote about Black lives. Even entries that are one sentence in length pack in the references: “F is for Ferrum, Virginia, Roberta Flack, and Fences,” and “O is for Oil lamps, the Ohio River, and Jesse Owens, who won four gold medals in the Berlin Olympics.” To catch the reader’s attention, the first letter of each entry on each spread that begins with the letter in question is capitalized and highlighted in a bold font.

Walker, weaving past and present, incorporates mention of Black artists (Romare Bearden); musicians (the Carolina Chocolate Drops, George Clinton, and Valerie June); poets (Effie Waller Smith and Crystal Good); playwrights and their work (August Wilson and Two Trains Running); sports figures (Satchel Paige and Aaron Thompson); civil rights activists (Edward J. Cabbell); historians (Carter G. Woodson); and much more. He commemorates educational institutions (Berea College and the Highlander Research and Education Center) and the breathtaking topography of Affrilachia (the Blue Ridge Mountains). Even I-64 makes the cut.

The appended eight-page glossary provides context for readers curious to learn more, but many of the entries will have readers seeking additional information elsewhere. “D,” we read, “is for the real Dukes of Hazard,” what appears to be a reference to the Ku Klux Klan. This is one of many examples of thought-provoking, conversation-starting texts that can generate rich classroom discussions — for young children and high schoolers alike — about Black history in this country. The same goes for other entries not covered in the glossary: “Environmental justice,” the “metal Lunch buckets” of miners, the quilts that “sometimes had secret maps for Harriet Tubman’s passengers,” “Steel mills,” and more. Many entries could seamlessly supplement history curricula: “the 1920 coal Miners’ strike in Matewan, West Virginia” and “Hawk’s Nest Tunnel tragedy,” the latter one of the biggest industrial disasters in this country’s history.

The appended eight-page glossary provides context for readers curious to learn more, but many of the entries will have readers seeking additional information elsewhere. “D,” we read, “is for the real Dukes of Hazard,” what appears to be a reference to the Ku Klux Klan. This is one of many examples of thought-provoking, conversation-starting texts that can generate rich classroom discussions — for young children and high schoolers alike — about Black history in this country. The same goes for other entries not covered in the glossary: “Environmental justice,” the “metal Lunch buckets” of miners, the quilts that “sometimes had secret maps for Harriet Tubman’s passengers,” “Steel mills,” and more. Many entries could seamlessly supplement history curricula: “the 1920 coal Miners’ strike in Matewan, West Virginia” and “Hawk’s Nest Tunnel tragedy,” the latter one of the biggest industrial disasters in this country’s history.

The illustrator, artist Ronald Davis, who goes by upfromsumdirt and lives in Lexington, Kentucky, fills these pages with bold colors, textured backgrounds, and hand lettering. He matches some of Walker’s entries with eloquent portraits, such as the “N” entry that features a smiling Nikki Giovanni and “D” entry that shows a smiling Denise McNair, the youngest of the girls who died in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing.

Next to the “W” entry is a dynamic portrait of Carter G. Woodson, saying via a comics-like speech bubble: “I Own February.” The “P” entry showcases Cool Papa Bell, “one of the superstars of Negro League Baseball,” leaping into the air, a kinetic line of motion and energy, to catch a ball in his mitt. In one striking spread, for the letter “U” (“U is for Underground”), Harriet Tubman turns to look at readers. She has the wings of an angel and a shotgun hanging at her side. On the same spread is mention of “Umoja,” the first of the Seven Principles of Kwanzaa, which represents “Unity of our family, community, nation, and race.”

And should readers forget that Black history is for everyone in the U.S. to learn, no matter the color of their skin, there’s the book’s penultimate spread: “Y is for all of Y’all.”

Julie Danielson, book reviewer and copyeditor, writes about picture books for Shelf Awareness, BookPage, and the Horn Book. She lives in Murfreesboro.