A Queerness Full of Appalachian Grit and Spirit

Zane McNeill discusses Y’all Means All, an anthology of emerging queer voices

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This interview was originally published on August 24, 2022.

***

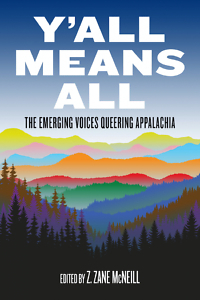

One of many Appalachian voices leading the region into more imaginative and inclusive realms of writing and publishing, Zane McNeill is a contributing writer with Sentient Media and Law@theMargins and served as editor for the anthologies Vegan Entanglements and Queer and Trans Voices. Their work on the ecology of the queer Appalachian landscape continues with a new anthology from PM Press, Y’all Means All: Emerging Voices Queering Appalachia.

In my own work as an editor for the University Press of Kentucky, I’m excited to have Zane as a board member for our burgeoning series called Appalachian Futures: Black, Native, & Queer Voices. In addition to serving on our board, Zane is also a co-editor on a forthcoming collection with the series called Deviant Hollers: Queer Ecologies & Bodies in Appalachia.

In my own work as an editor for the University Press of Kentucky, I’m excited to have Zane as a board member for our burgeoning series called Appalachian Futures: Black, Native, & Queer Voices. In addition to serving on our board, Zane is also a co-editor on a forthcoming collection with the series called Deviant Hollers: Queer Ecologies & Bodies in Appalachia.

In a recent email exchange for Chapter 16, we explored some of the intention behind Y’all Means All, giving a taste of how queer Appalachians are reimagining and reclaiming Appalachia’s future.

Chapter 16: “Y’all Means All” has been a phrase floating around for a few years. I know I expect to see it on crafty rainbow-colored signs at businesses in Appalachia and the South to express support for the LGBTQ+ community. How did you land on this title as a representation of emerging queer voices from Appalachia?

Zane McNeill: It’s actually sort of random that we decided on this title. Originally, we were under contract with an academic press and the title was something long-winded like “Queering Appalachia: Disrupting Normative Conceptions of the Region.” Something very academese-y. When we later pitched to PM Press, I changed the title to better represent the collection as we shifted from an academic audience to an activist-scholar/journalist/queer activist audience. PM Press was so surprised and excited that “Y’all Means All” hadn’t been snatched as a title for a book yet, so we moved forward with it.

The title inspired the graphic designer at PM Press to come up with its beautiful cover, which wooed the distributor and is so gorgeous in bookstores, so I’m glad that we picked “Y’all Means All” to represent the collection.

Chapter 16: Maybe it’s just the recovering academic in me, but I love a good table of contents. There’s a joy in seeing an essay collection with so many voices and specific perspectives on Appalachia and queerness. How do you feel about the synchronicity of voices as they came together in this collection?

McNeill: I am so proud of the contributors and the strength of their contributions — they come from all different walks of life, but they share a similar genealogy in their writing. This collection illustrates a queerness that is so hopeful and fun and messy, but also full of a very specific Appalachian grit and spirit.

If you look at each chapter’s notes and the book’s index, you’ll see which writers, activists, and scholars the contributors are in conversation with. There is just something so amazing and weird and fun about seeing a chapter that cites Jose Munoz’s theories next to a chapter in conversation with tree-sit blockade activists and alongside a piece on Mothman folklore as queer worldbuilding. It’s just so Appalachian — the hotchpotch of theories, personal narratives, folklore, and dream-making about queer futures all tied up and jumbled together.

Chapter 16: I too didn’t identify with my Appalachian upbringing until later in life after having moved away from the region. This seems to be a common occurrence that has a lot to say about the path to identity formation from rural regions. How does that retrospective identity formation play out in this collection, and what does that have to say about organizing in this region on the ground to our status sometimes as Appalachians in absentia?

McNeill: A lot of the contributors are Appalachian expats — many are doing Ph.D.s in states completely outside of the region. When Queer Appalachia’s zine Electric Dirt was published, many of us found a community and a language of rural queerness for the first time. The alienation that we had felt turned into community, which turned into this book. We were able to define ourselves in our own words, create and uplift queer Appalachian histories that had been eclipsed and erased, and imagine different kinds of queer futures.

I think for a lot of us this work, the chapters and the book and the conversations that it has created, is a way for us to stay connected with our roots and our culture. It is a labor of love. Many of us had to leave the region for one reason or another and found an urban queer culture very alien to us — we were told that there is not queer culture in Appalachia and had to defend the region from the stereotypes we encountered outside of it. But, as this book illustrates, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Many people feel like queers in rural spaces are trapped, and certainly some are, but so many people are forced to leave the region because of how extractive capitalism had torn apart our home. For me, this book is a form of activism and organizing and of creating community and archiving and dream-making for those who have stayed and those who have left.

I think for a lot of us this work, the chapters and the book and the conversations that it has created, is a way for us to stay connected with our roots and our culture. It is a labor of love. Many of us had to leave the region for one reason or another and found an urban queer culture very alien to us — we were told that there is not queer culture in Appalachia and had to defend the region from the stereotypes we encountered outside of it. But, as this book illustrates, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Many people feel like queers in rural spaces are trapped, and certainly some are, but so many people are forced to leave the region because of how extractive capitalism had torn apart our home. For me, this book is a form of activism and organizing and of creating community and archiving and dream-making for those who have stayed and those who have left.

Chapter 16: The idea of “non-reactivity” comes up a lot in this collection. How to “talk back” to the stereotypes in Appalachia without it feeling like a response that gives the dominant culture a placating example of the “Other.” What’s your best suggestion to writers from the region to do just that? How to show and not tell and to respond without reactivity as manifested in this collection?

McNeill: When we were doing our call for proposals for this collection, Appalachia was still being painted as “Trumpalachia,” and Elizabeth Catte’s What You’re Getting Wrong about Appalachia in response to J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy had just come out. Many of us liked the way that Queer Appalachia challenged stereotypes about the region by just letting queer Appalachians write and create and make and describe their identities and lived experiences.

I was volunteering as an editor for The Activist History Review (TAHR) at that time and felt that our way of offering a platform for scholar-activists to write their own histories was an extremely powerful form of advocacy. This collection was really framed by Queer Appalachia’s and TAHR’s approach to just being a space for historically marginalized voices to exist and thrive and create and collaborate and worldbuild and dream. Many of the contributors talk back to stereotypes of the region without centering them by speaking from their lived experiences. They disrupt normative discourses about the region by simply existing and by having a space to voice their existence. There is something so powerful about just existing when capitalism and white supremacy and everything tied up with that works to silence you. For other authors and advocates and journalists and academics and whoever else who wants to talk back to power, I would recommend just letting marginalized people speak for themselves — instead of speaking for them — by offering them a platform to do so.

Chapter 16: In the intro, you provide a bibliography of a handful of titles that have been published from this region suggesting queerness as a natural positioning for this collection. It just makes me giddy thinking about how many more books, acts of storytelling, and various forms of writing are in the process of forming to this end. As someone who has spent close time with emerging queer voices and has published several collections from this region, how do you see that trend continuing in the next decade? What does your Appalachian imagination see in revolutionary print form?

McNeill: I am very proud of this book, but I am even prouder to have been able to foster and empower these folks and build community with them. Many of us wrote our chapters in 2018, when many folks were at the start of their academic careers, really early in their Ph.D.s. Since then, we have been able to build scholar-activist editorial companies together, co-edit a special issue of the Journal of Appalachian Studies together, and publish so much cool queer Appalachian scholarship together. Many of the contributors in this collection are now nearing the end of their Ph.D.s and finishing their dissertations, publishing their own manuscripts, and building other projects together. I settled with the subtitle “emerging voices queering Appalachia,” but it would be more accurate for it to be the “erupting voices queering Appalachia.”

Chapter 16: Let’s hear a bit about what’s next for you. I know you are starting law school in the fall, and of course we have the forthcoming collection of yours for the Appalachian Futures series called Deviant Hollers: Queer Ecologies and Bodies in Appalachia. How do you see your work evolving as you enter law school and how that relates to your ongoing work in Appalachia?

McNeill: Yes! Deviant Hollers actually started as a sister project of Y’all and I’ve been working on it since 2018, as well! It is a little more academic than Y’all is, but it comes from a very similar conceptual framework and is written as accessibly as possible to empower changemakers, academics, direct-action advocates, and writers alike. It also has many of the same voices from Y’all as contributors thinking about queer ecologies, Appalachian natures, critical geographies, and challenging queer settler colonialism. In Y’all, I think through Appalachia as a queer region in and of itself — not just a space that queer folk live in. In Deviant Hollers, the contributors and I think through how whiteness and settler colonialism are present when white queer settlers queer a region and how and whether we even should, if Appalachia is a colonialist concept, imagine queer Appalachian futures. Some of these questions and explorations can be found in the special JAS issue, which features contributors from Y’all and Deviant Hollers.

As for my continued work, I actually see it all as connected. I was always planning on going the Ph.D. route, but decided, because the labor precarity of academia, to do a J.D. I have a B.A. in history and an M.A. in political science and, since graduating, have published and edited and written while working full- time as a paralegal and freelancing as a DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion] consultant. I have another academic collection coming out on public art, performance studies, choreopolitics, and protest that I’m super excited about and have started to get into journalism. I’ve written for In These Times, Law@theMargins, Waging Nonviolence, and Sentient Media, among other publications.

In law school, I’m planning on specializing in labor and whistleblower law and am interested in civil rights and community/mass defense work. I also do a lot of work in animal law and animal advocacy and have published books on speciesism, carceral logics, and racial capitalism. I advocate for nonprofit workers, am a board member of Rights for Animal Rights Advocates, and a member of the National Lawyers Guild.

All of my projects are public-interest oriented, rooted in disrupting capitalist logics, and oriented around protecting and empowering direct-action advocates. Hopefully, I can continue my writing in law school. There are a lot of cool activist-scholars/activist-lawyers I look up to like Nicholas Stump, who wrote Remaking Appalachia, Dean Spade, Michael Swistara, and Chase Strangio. I want to emulate their work. Right now, this shows up in my freelancing, where I mostly write about how the legal system screws over marginalized people and try to increase transparency/demystify legal processes for advocates to use that system against itself and protect themselves. I also write about social movement and direct-action advocates and am then able to increase media attention about these actions and raise the protesters’ voices. I want to go to law school to better understand how those systems work so I can be a better resource for activists and better write about these issues.

One way where I hope that this can intersect with my work on queer Appalachia is by working with ACLU-WV and other groups that tackle issues like abortion access and transgender protections in Appalachia. I also hope to stay involved in the queer Appalachian community and continue to make trouble together.

Davis Shoulders is a co-owner of Atlas Books, a cooperatively owned, independent bookstore in Johnson City. They also serve as a series editor for University Press of Kentucky’s Appalachian Futures: Black, Native, & Queer Voices.