Flowers Blooming in a Blizzard

Understanding the work of poetry and place

In one of the 50 vignettes that make up Catching the Light, Joy Harjo tells of receiving an image via Facebook Messenger from an old friend in Lukachukai, a mountainous area of the Navajo Nation in Arizona.

The friend describes the scene around him — mesa views and sound of his sister’s old truck revving up for a morning’s work and the scent of piñon pines and strong coffee. Although the message comes via social media, Harjo recognizes it as “prayer language” — not a traditionally religious term here but rather one meaning “attention to the atmosphere of place and time” and to “how language is happening.”

“Language is a living being,” she writes. “It is feeding this image, giving it a place to live in my imagination.” Language is also born of place, connecting us to Ekvnvcakv, or Earth. “Consider that the Earth mind, architectures, and aesthetics shape the mother root of our imagination here.”

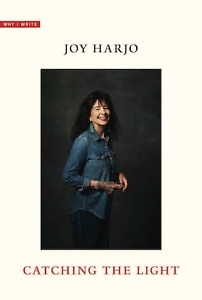

Part of the “Why I Write” series at Yale University Press, a collection of short books about writing by single authors and based on Yale University’s Windham-Campbell Lectures, Catching the Light is rich with Harjo’s observations about language and place and imagination and the work they do in the world — observations gathered over the course of a lifetime as a poet, memoirist, musician, and three-term U.S. Poet Laureate.

A member of the Mvskoke (Creek) Nation who grew up in Oklahoma, Harjo contrasts the indigenous languages of the Americas with ordinary English, which she calls a “trade language” valuable for practical uses. English can be a language of “alliance, connection,” she says, but to her the indigenous languages “carry in them the plants of the area, star maps and meaning.”

The book might be described as a hybrid. The pieces are short — some just a page or two and others as long as six or seven — but they are not strictly essays and certainly not “flash,” the popular genre of “short-short” or “sudden” nonfiction, despite their length. “Meditations” is a more apt description, with some reading like personal narrative and others like prose poems, imbued with subtle nods to craft.

The book might be described as a hybrid. The pieces are short — some just a page or two and others as long as six or seven — but they are not strictly essays and certainly not “flash,” the popular genre of “short-short” or “sudden” nonfiction, despite their length. “Meditations” is a more apt description, with some reading like personal narrative and others like prose poems, imbued with subtle nods to craft.

The early pieces blend narrative elements that those familiar with Harjo’s memoirs, Crazy Brave and Poet Warrior, will recognize. Here we learn again of Harjo as a teen in 1967 leaving an abusive homelife to attend the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. She calls this her “origin story” as a poet, which she contextualizes in terms of the cultural shifts of that time, including the Vietnam War and the burgeoning arts movement among Native youth.

Elsewhere, she describes her current home in Tulsa, Oklahoma, near where the 1921 race massacre took place and where poetry has an important role. “As the search goes on for mass graves, poems are being commissioned and written as testimony and witness, so this act will not go unremembered, unspoken.”

She offers narratives about other people, illuminated with unpredictable insights. In one vignette, she tells of a night long ago in Milwaukee when a “mysterious” Native woman in a red dress appeared at the door of an Indian bar.

The bar was full of mid-week regulars, drinking despite an imminent blizzard. At first seeming like a vision, the woman came in from the snow, ordered a drink, then another, and then when Kenny Rogers came on the jukebox, she climbed on a table and began to dance and sing, taking her clothes off as men sidled up to be closer and women looked on disapprovingly.

To a lot of writers, this might simply be a sad story about a drunk woman, but Harjo sees it as a kind of miracle, at least to those in the bar. “This was a crowd that had seen everything — their lands stolen, starvation, massacres, children taken away and returned shorn of memory. They were all stopped by the miracle. When the song was over, the spell was shattered.” For the woman she feels continuing empathy, a gesture delivered poetically. “When I remember her, I see tall stands of pine trees around a clear, deep lake. It is early morning and the sun is casting flickers of light through the trees.”

Near the end of Catching the Light, she describes dreams from “the dark period of Covid isolation,” when she went inside and “to the inside of inside.” In one dream, she meets her daughter’s sixth-great granddaughter and realizes she is at her birth, where she “walked with her into time and delivered the baby to the Earth story that needed her.”

Part of the beauty of Harjo’s work is her ability to take us seamlessly between here-and-now reality and visions. “Where do we come from? Where do we go?” she asks. “And what of politics, war, and love? What is the sense of it all?” The answers, Harjo suggests, lie in the questions themselves: “It is the singers, poets, and storytellers who are captured by the expression of this eternal drama, and with language, metaphor, timing, and melody create meaningful shape. What is repetitive and ordinary becomes flowers blooming in a blizzard.”

Jane Marcellus’ published work includes literary nonfiction, critical analysis, and journalism. Her work was listed as “Notable” in Best American Essays 2018, 2019, and 2020. She is a former professor at Middle Tennessee State University and now works as a freelance writer and editor.