Brownsville

I wasn’t worried about getting there on time, but I was worried about the drug test

“I hope you won’t have any problem taking a drug test, will you?” the Brownsville Herald’s editor-in-chief asked me over the phone. “We require all our new hires to pass one.”

It was 1994, and she was actually offering me a copy-editing job in the Texas border town, after I had sent out nearly 100 resumes across the country without a single positive response. I was eager to run away from a bad divorce and the death of my father and was desperate for a job that would take me away from Nashville. On the phone, I stressed my copy-editing experience and Spanish fluency, and apparently that was enough.

It was 1994, and she was actually offering me a copy-editing job in the Texas border town, after I had sent out nearly 100 resumes across the country without a single positive response. I was eager to run away from a bad divorce and the death of my father and was desperate for a job that would take me away from Nashville. On the phone, I stressed my copy-editing experience and Spanish fluency, and apparently that was enough.

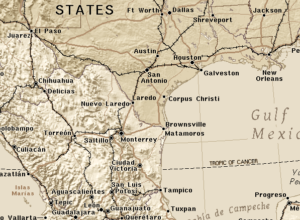

The classified ad I answered in Editor & Publisher had been running for five weeks, and she was enthusiastic enough that I figured it must not have had many responses. Brownsville, like all Texas border towns, had a high percentage of Mexican-American neighborhoods, modest homes with dusty yards, Mexican culture and cuisine. The predominant spoken language was a mix of English and Spanish. The salary was distinctly entry level. It was apparently not a job that most beginning copy editors in search of work were interested in, but it looked good to me.

“When can you start?” she asked. “If you can get to Brownsville this week, I can say you’re hired.”

“You can count on me,” I responded with no hesitation.

It was only 1,100 miles south of Nashville to Brownsville, the most southeastern point of Texas, and the money she mentioned, while modest, would ease a lot of my troubles. The drive would be a snap for my old Toyota, and I didn’t have much in the way of affairs to wrap up. I wasn’t worried about getting there on time, but I was worried about the drug test: to wit, that I had smoked a little weed that very day, and the day before that, and even the one before that, etc., and word was that a drug test within as long as three weeks of inhaling would show a positive. Still, I was elated that someone was willing to hire me, and I had always wanted to get to know the melting-pot frontier, that third nation at the border of Mexico and the U.S.

“Great, see you this time next week,” I assured her, and as soon as I hung up I dialed my friend who I’ll call Louie. If there was anyone I knew who could tell me how to beat a drug test, it was Louie. He had bragged to me about doing so to get the security guard job he had held for four years, where he’d gone into every single shift fried. He habitually rolled joints as big around as my middle finger. An unashamed viper.

“No problem,” he assured me over the phone. “Use my tried-and-true method and your pee will come out clean as an evangelical Christian’s…well, probably even cleaner,” he laughed. “What you gotta do is make your piss so acidic that the THC won’t show up. Works every time but you gotta be willing to do it, and there’s them who can’t, or they start and don’t finish. It tastes pretty bad, I’ll allow you that, but it works.”

That’s why I was in a ratty Brownsville motel the night before my first day of work and scheduled drug test, with a quart of orange juice and a pint of white vinegar on the scarred bedside table, along with a plastic glass from the nasty bathroom. It took me three hours to empty that pint bottle — filling that glass three-quarters full of OJ, and topping it off with vinegar, gagging the whole thing down while watching baseball on a beat-up television. God almighty, it tasted bad. Only the prospect of a job …

***

Everybody has their own theory about when peoples’ bodies, whereabouts, and conversations were no longer their own, but were subject to examination at any time and to any degree, when surveillance of an innocent person became perfectly legal. What most everyone can agree on is that damned little in our lives is private anymore, and this state of affairs came to pass quickly, within one lifetime.

I have a friend who pins it on the disappearance of those public telephone booths with sliding doors, which you closed before dropping in your coins and making a call. Those booths were virtually soundproof. What was said stayed between the caller and the called. The booths gradually disappeared, first replaced by more economical (but less private) half-body shields made of thick plastic built around a pay phone. Telephone booths became relics. Cell phones were gradually introduced; the chip was implanted in the body public; and good luck finding a surviving pay phone of any kind. Not only were cell phones made to be used anywhere, talking in a crowd, on a bus, or a sidewalk, but they also revealed to anyone who wanted to know exactly where you were at all times, your movements as well as who you were calling.

I agree with my friend that cell phones are a link in the transition from private to non-private, but my own particular sense of when we had our personal intimacy definitively violated was when people agreed that a prospective employer had the right to require we urinate in a bottle.

***

I managed to down all the orange juice and vinegar, and even slept a few hours before reporting for work the next morning. The editor was a thin, harried, stressed woman with bags under her eyes who was short of copy editors and really glad to see me. She repeated what she had said over the phone: “I hope you won’t have any trouble taking the drug test. That’s the first order of business this morning, and then we’ll talk about the job.”

She drummed her fingers on the steering wheel as she drove me to a clinic, not far from the newspaper. My palms were sweating and my stomach was still complaining about the OJ and vinegar. At the clinic a woman dressed in nurse’s whites handed me a glass urine-sample bottle and directed me to a closet with a sink and toilet in it, telling me to fill the bottle at least halfway. I knew there were websites offering, for $100, the urine of individuals guaranteed to be substance-free. As I handed the bottle back to the nurse, I worried that maybe I should have spent the money. Louie was a good guy, but not necessarily wholly reliable.

Before we went back to the office, the editor said she wanted to show me something. She drove to a plaza downtown, five minutes away, and parked in a lot above a river, which flowed through Brownsville on its way to the Gulf of Mexico. “Look,” she said getting out of the car, and gesturing toward the river. “This is the Rio Grande, and there on the other side is Mexico. Matamoros, Mexico. In Matamoros, they call the river the Rio Bravo. Look at that.”

She pointed at three people, an older man, a woman, and an adolescent boy in the middle of the river, each doing a sidestroke with one hand, while using the other hand to hold a bundle aloft and dry. “That’s our country’s border security,” she told me. “All you gotta do is be able to swim if you want to reach freedom.”

***

Freedom. That was actually the name of the media conglomerate that owned the Brownsville Herald along with a number of other newspapers, including the Orange County Register in Southern California, which was Freedom Communications’ flagship enterprise. The corporation also owned numerous small newspapers, including three along the Texas/Mexico border. Freedom Communications would file for bankruptcy a couple of decades in the future, but when I was hired it was a thriving company, an editorial supporter of the Libertarian Party, which in turn was a vocal proponent for abolishing the prohibition of all drugs, believing the government should not dictate what a person can and cannot ingest.

Freedom’s man in Brownsville was named Doug Hardie, and he was on the Herald’s masthead as its publisher. He often passed through the newsroom from his office in another part of the building. He came in a few days after I had started work to deliver the news about my drug test. “Congratulations, you passed with flying colors,” he told me, and invited me out on his comfortably appointed boat the following weekend to fish for red snapper in the Gulf of Mexico. After reeling in a couple of snappers, and downing a couple of Lone Star beers, I felt loose enough to ask him if he didn’t think it was a little contradictory for a newspaper associated with the Libertarian Party to require a drug test from its employees?

“I guess so,” he mused, shrugging his shoulders, “but the insurers require it.” End of conversation.

***

My first evening on the copy desk at the Herald, the city editor and everyone else in the newsroom took a break to go up the street to a café and have a snack, leaving me on duty. “Back in 20 minutes,” the city editor told me as he left. “We’ve got plenty of time to put it together.”

Not five minutes after they went out, the phone rang and it was somebody at the police station notifying the newspaper that cops had busted a downtown warehouse with 500 pounds of marijuana bailed up inside. Five hundred pounds! In Nashville that would have made for a front-page headline. I hung up and ran up the street to the café to tell the city editor, who I found comfortably seated in front of a bottle of Lone Star.

On hearing my breathless news flash, he flapped a hand in dismissal. “Small potatoes here. We’ll give it two grafs on the inside. Now get back to the newsroom. Don’t ever leave it empty again on your shift, or you won’t have a newsroom or a job to come back to.”

I lasted six months in Brownsville before tiring of the nightly brain strain and the terrible summer heat. I beat feet back to Nashville. These days in downtown Brownsville’s broad daylight you won’t see anyone swimming across the Rio Grande to reach a better life. These days also, across the United States, labor is in extremely short supply. Just try finding a carpenter or stone mason willing to do a couple days of work; plumbers and domestic workers are hard to find; minimum wage jobs go begging; businesses close for lack of staff; and thousands of immigrants — job seekers almost all of them — are denied entry at our borders, which are subject to much tighter vigilance than in 1994. The same can be said for our lives and our bodies, the details of which are, for each and every one of us, available on demand.

Copyright © 2023 by Richard Schweid. All rights reserved. Richard Schweid is a Nashville native and the author of more than a dozen books, including Octopus, Invisible Nation, and The Caring Class. He lives in Barcelona, Spain.