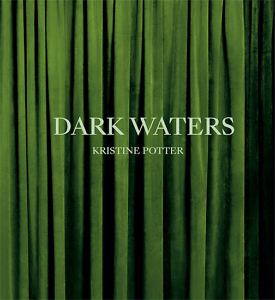

Southern Gothic Time Warp

Kristine Potter’s photography goes deep

Tennessee-based photographer Kristine Potter’s widely celebrated body of work explores the landscape of the American South, masculine archetypes, and mythologies of the past. With her latest book, Dark Waters, she builds upon these obsessions and introduces her first studio portraits inspired by the women that populate American murder ballads. These portraits work powerfully in conversation with Potter’s ominous landscapes in intuitive ways, creating currents of visual energy that overlap and build throughout the monograph. While the ballads create an affecting emotional ether around the pictures, the book trusts the viewer to make further connections. The result is a haunting, empowering visual experience steeped in literary and musical traditions.

Chapter 16 recently connected with Potter to ask about murder ballads, bodies of water with violent names, and how she maintained an open-ended art of seeing as she captured the evocative pictures in Dark Waters. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Chapter 16 recently connected with Potter to ask about murder ballads, bodies of water with violent names, and how she maintained an open-ended art of seeing as she captured the evocative pictures in Dark Waters. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Chapter 16: You’re currently based in Nashville, but I was curious if you also grew up in the South? Are there other Southern states and regions captured in these photos?

Kristine Potter: I wasn’t born in the South, but I was in Georgia by the age of 5 [and] all the way through college, where I went to the University of Georgia. But interestingly, when you grow up in a military town and come from a military family, culturally you’re not exactly Southern. Most military families move around a lot, and by circumstance it just turned out that ours didn’t. So my family isn’t exactly Southern, but I grew up in the South. These pictures were made in the broad Southeast: Kentucky, the Carolinas, Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, Florida, and Louisiana.

Chapter 16: Central to the book is a recurring theme of violence against women, particularly in the lyrical tradition of murder ballads steeped in a Southern gothic landscape. You include an appendix of recorded versions of these songs, and I wonder if you grew up listening to any of them? How did these songs come to inspire your work and what was the process of deciding to include lyrics throughout?

Potter: I didn’t grow up listening to them, and I would say I was only mildly aware of their existence. I’ll say two things about it. I do use them as a device here, but I hope that when people think about popular culture, no matter when and including now, [they] realize that “the dead girl” trope is very active — in serial television, in cinema — and if the show or the film doesn’t revolve around the death of a woman, it certainly includes abused women somewhere, almost always. So I think I’m using this as kind of a niche way to bring context to this, but I do hope people realize that part of listing the songs and [noting] how contemporary musicians still record these was a way of saying, Hey, this isn’t just positioned in the past, and I hope this notion of what’s commodified and what’s considered entertainment is considered also.

How they came to be integrated into this work: I was living in Queens with my husband, who’s a musician. We were planning on moving to Nashville, and he was working on the American songbook. He was saying, Hey, if I’m gonna pick up gigs in Nashville, I gotta know all these songs. Our studios were side by side, and I remember one day hearing a murder ballad. I was editing some of these landscape pictures already, and I went in there and asked. What’s so funny about him — he’s so focused on learning the music, the chord changes — he isn’t focused on the lyrics so much. And he said, You know, there’s a couple of murder ballads in the American songbook. And I got really interested in them as a form of storytelling.

I started researching them and realized that I had heard a number of them. Also, while the murder ballad tradition is about murder, many of them detail the murder of a woman at the hands of a man for whatever inconvenience she represents: She’s a mistress, she became pregnant, she won’t marry him, she’s below his station — you know, the list is the same as it always has been. That became an interesting intersection with the other pictures I had been making of bodies of water with ominous or violent names, which is where the work started. This integration of murder ballads came half a year into that endeavor where I found, oh you know, if we think about the history of the Southern gothic tradition and what we expect artists to produce in the South, there’s often a darkness to it. I was questioning whether the landscape bore any influence on that: if the history of violence in the South remains, if there’s an echo. I was interested in the relationship between cultural production and the history of the landscape itself.

Chapter 16: That’s beautiful. I love that water was the inspiration point for looking into these dark themes.

Potter: You know, I’m not an overtly conceptual artist — I mean, I have conceptual tendencies — but I also just go out in the world and make pictures and learn as I go what I’m interested in. So the framework was: Okay, I’m gonna find these bodies of water on a map — I’m gonna drive to them and see what I find. The work sort of evolves as it’s being made. But that was an architecture to move me around in the landscape.

Chapter 16: And that allows you the freedom to be a little bit improvisatory.

Potter: Yeah, that’s exactly right. I believe I will find something in the world, or the world will deliver. It is the act of looking and being open that allows me to see. If I’m too directed, in a way, I’ll probably miss the point.

Chapter 16: Throughout the book there are portraits of women who appear to have risen from a body of water and stand before the camera, sort of defiantly dripping. How do you conceive of these women’s relationships to the women in the ballads?

Potter: This was a real departure for me as an artist. Again, I think I’m known for going out in the world and making pictures, and I’d say 80 percent of this [book] is made that way. But the portraits are different — they’re made in the studio. For me, it was important to integrate this imaginative level of representation into the work. All the women in those portraits are named after the victims in the murder ballads: Knoxville Girl, Omie Wise, Pretty Polly, to name some of the better-known ones. And [the portraits] are meant to disengage them from that history.

In some cases, murder ballads, like broadsides, are recounting actual historical events. In other cases, they’re completely fabricated, and in some cases, we don’t know. But I liked the idea that I could change the ending. Or that these women sort of existed in two ways: One would be an act of defiance – but also, so much of this book, to me, while it is about the real world, it’s also about a woman’s psychic space. Like, when you walk through a parking lot at night, you know, you have a vulnerability. Maybe you have your keys in your fist, or maybe you just take some extra looks around. That psychic space has been informed by our own experiences, stories we’ve been told, movies we’ve watched, songs we’ve heard — so much.

The very first picture you meet in the book is a woman with her eyes closed. For me, I’m bringing you in through the woman’s psyche. Like, these are the stories in our heads. So the reason the studio portraits are in black, for me, is also to — in my mind, psychic space is darkness and little things come up — to put new images in our heads that didn’t end with a woman sinking down the river, but a woman sort of defiantly engaging. You know, that is subtext. Whether anyone puts those pieces together is out of the realm of control, and I don’t want to tell people how to read the work, but that’s why I built them that way.

Chapter 16: I enjoyed the feeling of timelessness in these pictures; it feels as if some of the images could have been captured in nearly any era, and that unfortunately feels resonant with the issues of toxic masculinity and misogyny. Will you share a little bit about your relationship to creating photos of present-day moments and weaving those into a larger aesthetic that echoes a mythologized past?

Potter: It’s funny, I get asked a version of this question no matter what I’m working on. I sometimes really don’t know how to answer, because on some level it’s instinctual, or [it’s] the use of black-and-white. Black-and-white already disengages from reality in a way that makes it less indicative of our contemporary experience. Perhaps it’s my choice of what I look at, and perhaps there’s something else at play that I can’t totally put my finger on. But I do like the idea that time is a little bit slippery.

Potter: It’s funny, I get asked a version of this question no matter what I’m working on. I sometimes really don’t know how to answer, because on some level it’s instinctual, or [it’s] the use of black-and-white. Black-and-white already disengages from reality in a way that makes it less indicative of our contemporary experience. Perhaps it’s my choice of what I look at, and perhaps there’s something else at play that I can’t totally put my finger on. But I do like the idea that time is a little bit slippery.

If you’re paying attention, there are little clues to when and where we are, and then there are these things that throw you back 50 years or 60 years. That is really a circumstance in a lot of my work, but really true in the South — that you can have these moments that feel incredibly contemporary and then you’ll have this time warp, where you’re like, is this the 1970s? Why is there wood paneling everywhere? Time doesn’t feel totally fixed here. I do like that about the pictures.

I’ve been asked this question in reference to the studio portraits and the clothing the women are wearing. And I realize, God, some of them almost look like a period piece, like Victorian, but that was not on purpose. Sometimes with the age of the [young] people I’m photographing, when told to “wear something feminine and without logos,” without question, everyone would bring these dainty, floral dresses or white ruffly things. But, you know, 20-year-olds wear this stuff — this is coming right out of their closet. And that’s interesting to me, too, the way retro style works — and the way we want to embody certain elements of the past, almost fetishistically, but also move forward progressively or socially. So all of that is in the pictures, too.

But this thing happens where I’m driving around deep hollers of East Tennessee, and I do come across a 1950s car crashed into a ditch. You do feel like you’re in a time warp. I try not to make cliched pictures of the South, because I don’t think we need any more of that — but every so often you are kind of struck by that circumstance. Where am I? That happens.

Chapter 16: The photo of the car crashed into the ditch is titled “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” after the Flannery O’Connor story. I wondered what made you think of that story?

Potter: It was instantaneous. I was in search of “Hell for Certain, Kentucky.” You know that experience where you have your GPS on your phone, and then it just turns into a blue dot on a grid? And I was like, Oh dang, am I gonna know how to get back to any main road? Because I was deep, deep in it. And I came across this car ditched into a ravine, and the car was shiny — it hadn’t been there for long. That was what was most bizarre about it, of course, the car was very old, but it had not been crashed there for more than a few days.

That was so odd to me, and I stopped to just look at it, and there I am, on the edge of the forest, and I have this car crashed in the ravine from that era, and I’m like, This is that story. The grandmother and her grandkids are in the car, and they literally crash into a ravine — and then The Misfit comes up with his cronies and they take the kids into the forest while the grandmother is still on the road, and so on. And I had this flash — something I hadn’t read for a very long time, it was like I had just stepped into it or something. Again, if we want to talk about how the stories of the South live in our psyches or live in this space that we conjure when we see things… maybe it’s Flannery O’Connor, or maybe it’s any of a zillion movies or TV shows or songs.

Chapter 16: In one photo called “The Cliff,” the composition of a cliff and its reflection in the water below struck me as appearing almost like a cathedral. It evokes a kind of dark, gothic site for ceremony within that psyche-space of the rest of the book. What was the process of choosing landscape photographs for this project which deals so much with humanity?

Potter: That one got turned sideways, and it’s the only picture that does that — where gravity sort of shifts. It begins a chapter where a woman is spun around: You get to a landscape that’s tumbling, then you see this upside-down landscape, then you get to looking straight down. I wanted to create a mini-chapter of getting run ragged: I see up, I see down, I see sideways, I fall into the water, I look straight up. I wanted to, in that portion, maybe put you in the eyes of one of these women — or at least disorient you. The disorientation comes from the tumbling, the spinning, the shifting gravitational space of the pictures.

[As for] the other landscapes … well, I’ll say this about titling pictures. Historically I would never do it, other than for practical reasons. I never wanted to create too much direction in the reading of the pictures. But this is the first body of work where titles are really activated. I’m distrustful of language and image — even though I think it’s incredibly powerful – language is so powerful, it knocks the nuance out of pictures. So I’m really careful about how I integrate it. I started thinking, I’m going to these bodies of water because it’s called Bloody River or Rape Pond, or Dead Man’s Branch, or something, and I thought, well, that’s gimmicky. What if the picture is only good because it’s called Rape Pond? I need to make a picture that holds energy. Regardless of the title, the picture has to do the work. So to answer your question, I feel like the landscapes that made it to the edit are the ones that hold the energy I need them to hold, and not just for their name. And there are rivers and bodies of water in here because they don’t have violent names, because I might’ve showed up to them for tangential reasons and the pictures held that energy. That’s the deciding factor of what gets used or not.

Lauren Turner is a writer and musician (Lou Turner, Styrofoam Winos) in Nashville. She is an M.F.A. candidate in poetry at Randolph College and the author of Shape Note Singing, her debut chapbook from Vegetarian Alcoholic Press. Turner’s latest record, “Microcosmos,” has been featured in Uncut Magazine, Pitchfork, and on NPR’s All Songs Considered.