Building on Reality

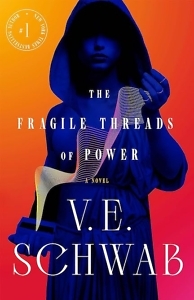

V.E. Schwab on her new fantasy series and whether she’s a Southern writer

Nashville native V.E. Schwab continues the story begun in her Shades of Magic series with The Fragile Threads of Power, the first in a new trilogy that returns readers to the Four Londons seven years after the events of the first series. Fans will be thrilled to learn what happened to Kell and Lila and all the other fascinating characters, but this book introduces new characters and complications.

The Four Londons (Red, White, Black, and Grey) still operate distinctly from one another, with only a few powerful magicians (Antari) able to move between them. The new Antari queen in White London will do anything to preserve the safety and well-being of her people, and the king of Red London is facing an uprising that threatens to destroy his people’s peace and prosperity. The Fragile Threads of Power is a compelling, fast-paced, and sturdily built fantasy, and whether a returning fan or a first-time discoverer of the brilliantly designed Four Londons, readers will enjoy every twist of this sharp novel.

Schwab talked with Chapter 16 by phone. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Chapter 16: I wanted to start by asking you about the relationship between this new book and the Shades of Magic series. I had not read that series before diving into The Fragile Threads of Power, so I know that you can read this one as a standalone. But what do you think would be added to the experience for those readers who have already been in this world and fallen in love with these characters?

V.E. Schwab: Of course, yes! My goal is that one day, when both trilogies are on the shelves, you’ll genuinely be able to choose which one you want to start with. Either Shades of Magic will feel like a prequel series or Fragile Threads will feel like a sequel series. Currently the only people who are absolutely adamant that you need to read Shades of Magic first are, of course, those who have read Shades of Magic first. And I understand. That’s the order that I wrote them. I think there’s some nuance and backstory, and I do my best to summarize it for you in Threads of Power, but if you find yourself falling for Kell and Lila and Rhy and Alucard, and would like to spend more time with them, then Shades of Magic is really their origin story. Threads of Power is their aftermath, and it’s the beginning of the story for a new set of characters.

Chapter 16: It’s obvious that you’ve dwelled with these characters for some time now. I’m curious: There are lots of authors who put a book to bed (a single title or a series), and then they find that the characters keep knocking at the door and saying, “Nope, we’ve got more to do.” Is that what happened here?

Schwab: I don’t do anything without intention, to an extreme degree. I’m a rigid planner. When I sit down to write a book, I already know the ending. So when I started A Darker Shade of Magic, I already knew not only the ending of that first book, but the ending of the whole trilogy. I’m also a writer who doesn’t believe in continuation for continuation’s sake. I need to have a reason to carry on besides a series being beloved or selling well because the author lives with a book for a very long time before a reader ever lives with it. Especially with a sequel series like Threads of Power. I don’t want it to feel like a redux. I don’t want it to feel unnecessary in any way. I was about halfway through writing book three of Shades of Magic, and I realized I had a small plot thread I could either rapidly resolve, which felt like a disservice to the plot thread, or I could use it as a little doorstop — to prop the door to the world open just in case I ever wanted to return to it. By the end of that series, I knew I wanted to return.

I spent the next three years analyzing that desire and beginning to build the foundation of the new trilogy and stress-testing it every which way to make sure it was necessary. To make sure this was something that had actual meat on its bones. I’ve always been fascinated with origin stories and how when we meet somebody, they are in that moment a product of everything that’s happened to them. All of their decision-making is a result of how they’ve been treated and how the world has interacted with them. I did have a degree of intrigue about how my characters would process and grow from and mature through the things that happened to them in Shades of Magic. I also had an interest in seeing how a world would mature, how power systems would change over time. And seven years felt like just enough time for our cells to regenerate and for us to mature through a generation — to go from young adulthood into adulthood or from childhood into adolescence. All of these interests began to coalesce, and about three years after, I was ready and convinced I wanted to do a new trilogy.

Chapter 16: That careful hand is evident throughout. I consider myself a professional reader, someone who can see what a book is trying to do, but I also love when a book surprises me, when it keeps certain things hidden until just the right time. Hidden things or deception — a presentation of one face to the world while keeping another face disguised — is a common thread in this novel. Do you think deception is at the heart of every power struggle? Or is there a possibility for what we might call an “honest” or transparent power struggle?

Schwab: That’s one of the great questions of the book. It’s something that everyone is struggling with: from the king of Red London, Rhy, to the young queen of White London, to a 15-year-old runaway, to Kell, who has had a vast amount of power his entire life and suddenly doesn’t. It’s less about whether there’s something like honest power, and more about how people with power use it. Are there honest ways to use that power? And how people without power obtain it, and are there honest ways to do that?

Schwab: That’s one of the great questions of the book. It’s something that everyone is struggling with: from the king of Red London, Rhy, to the young queen of White London, to a 15-year-old runaway, to Kell, who has had a vast amount of power his entire life and suddenly doesn’t. It’s less about whether there’s something like honest power, and more about how people with power use it. Are there honest ways to use that power? And how people without power obtain it, and are there honest ways to do that?

We have a rebellion, for instance, which is gaining traction on the ground and claiming that the king must be thrown out because he doesn’t have magic and it’s polluting the world. And then the question becomes does that rebellion even believe what they’re saying, or is it simply a convenient reason to attack the throne? So you’re right, a lot of it is about the honesty behind the action. You have the queen in White London who truly believes that she is doing what is best for the world. You have the merchant’s son who believes he’s going to be the hero. You have a lot of characters trying to make good choices. Most of my novels circle the concept of morality and whether it actually exists and whether there’s any such thing as a purely selfless act, or if we all act with at least a measure of self-interest at all times.

Chapter 16: That makes me think of my favorite character. I love the way Tes lives inside her beautiful talent even as she is forced to hide behind the fake Mr. Haskins to be accepted. It’s a quiet example of the many forms empowerment can take.

Schwab: Yes, to her it’s a form of art. The series really plays with the concept of a deific force, like “Do you see magic as a god?” In some ways, what Tes represents is the one-to-one spirituality between her and her magic, outside of the institutions of religion. It’s intimate. I think there’s something, too, about being an adolescent girl and the level of confidence felt on the inside versus masking that has to happen on the outside and the ways people see them as an object not a subject, something to be used like a tool. And Tes just wants to play. She cannot imagine a world in which she doesn’t use her power. She’s trying to find the safest option for herself, a place where she can hide but still engage with this ability so intrinsic to her.

Chapter 16: And as she matures and is forced into a deeper understanding of who she is and what she can do, she has to grapple with that question of morality, and I think, does so beautifully.

Schwab: Exactly. For a long time, her magic only affects her, so she’s able to live in a vacuum and make choices based solely on what’s best for her. She’s the kind who will cut and run in danger, feeling that everything that is not me can be rebuilt or remade. And of course later in the book, she’s faced with a moral quandary where another person’s life is in her hands, another person’s power. And she refuses because she doesn’t want that responsibility, doesn’t want to have to make hard choices. But of course, the thing we discover is that the simple act of having power means you will have to make hard choices with that power.

Chapter 16: Underlying all of that is the sense that magic can’t be made, but everyone’s supposed to have it. Power is synonymous with magic, but it’s not something that is denied anyone, or if it is, it’s notable that they don’t have it.

Schwab: Yes, it’s meant to be intrinsic. Also, when I was backbuilding Shades of Magic, the concept of the world’s relationship to magic is at the core premise. I wanted to design four worlds, and instead of designing them as geographically distinct, interlocking places, I wanted them to be the same world, each with different relationships to magic. So we have our world, the Grey World, where magic has been forgotten; the Red World, where magic thrives and so do its people; the White World, where magic has been traditionally bound into servitude and resisted; and the Black World, where magic became so intrinsic, so innate, people let it into their hearts and minds, and it devoured everything. So it is a gradation.

Chapter 16: And it’s wildly effective to think about those worlds as a continuum rather than a distinct geographical location.

Schwab: It allows me to develop that moral gray. Literally, we are operating in a spectrum. And each place has its own relationship to magic, which is almost an environmental factor. And then the people within that place have their relationship to magic, and it differs. In White London, traditionally, for many years, whoever had the most took the throne by force, and it made a very brutal, simplistic sense. Whereas obviously the system in Red London is vastly more complicated and much more delicate, much more nuanced. But it is proving just as problematic for everybody there.

Schwab: It allows me to develop that moral gray. Literally, we are operating in a spectrum. And each place has its own relationship to magic, which is almost an environmental factor. And then the people within that place have their relationship to magic, and it differs. In White London, traditionally, for many years, whoever had the most took the throne by force, and it made a very brutal, simplistic sense. Whereas obviously the system in Red London is vastly more complicated and much more delicate, much more nuanced. But it is proving just as problematic for everybody there.

Chapter 16: You said about your planning process, “that you propped the door open” — and there is that concept of moving between those worlds, the doors that can be built between them. Why was it important that those worlds interact?

Schwab: There has to be a point of intersection because that’s where conflict is. You can try to control everything that happens in your world — I mean, it’s a fallacy, but you can try — but there has to be an external factor that is truly outside of your control. I think that liminal space has traditionally been the most interesting one. You can have your whole world under control, and something comes externally to force it out of balance.

I also needed the worlds to touch so there could be a sense of awareness of what the others have — that grass is greener concept, which has traditionally built a huge amount of conflict between Red and White, because these two worlds sit side by side and have such vastly different relationships with magic that there’s a sense of coveting. The vast majority live in ignorance is bliss, but the few who can see and move between the worlds are burdened with the knowledge of the larger scope of what’s happening. They’re then forced to face their responsibility for it, their interconnectedness. You can’t live in the dark.

There are very few easy choices in this series. Very few cut-and-dried heroes and villains. Everyone is trying to act either from a place of self-interest or a concept of greater good.

Chapter 16: As we find with interactions with the queen, where Lila and Tes don’t trust her, and readers likely don’t either. But she insists that what she’s doing is for the right reasons: family, security, the crown. And you can’t quite fault her for that.

Schwab: She’s a very Machiavellian character, and perhaps one of the most clear-seeing characters. She’s really unburdened, perhaps because she’s a scientist. She’s looking at it from a place of odds; she’s making the scientist’s argument, the rational argument, which is, if we can find the ability to actually alter who has magic, why shouldn’t we? Of course, the argument is that the greater nature of things, whether you want to call it a god-system or magic, has apparently bequeathed magic to each person unequally. You can see that as arbitrary, which is what she does, or you can see it as god-given, as others do. It’s interesting because how you see that changes your relationship to your own magic. Kell, for instance, does not feel entitled to be an Antari; he believes it’s arbitrary. He does not believe he was chosen, yet everyone around him says he was. Whereas if you believe, like Ezril the priest, that magic is a god form, then how dare you? How dare you step into the river and try to change the current?

Chapter 16: Your relationship with magic is as personal as your name. Tes, for instance, guards her name carefully. (“Is it so hard to give?” asked the queen. “It is,” said Tes, “when you don’t have many things to call your own.”) Why do you think names are so important in this world, and would you say they are equally important to you as an author? Would Tes have worked just as well as a Desdemona or an Agnes?

Schwab: I am somebody who thinks a lot about names, but not in the way you might think. I didn’t have a name for the first few weeks of my life; my parents said they wanted to live with me first. And I am similar when it comes to my characters. Because I do so much planning before I ever start writing, I’m living with them and testing names on them for weeks. Very few characters come with a name in hand. I think Tes is the 17th name I tried; I could not find the right name for her. Desdemona would not have worked! I just kept trying things.

The names often end up falling into two camps: They’re either assigned by someone else — like Kell, whose name is not actually Kell. It’s a K and an L that was on a dagger found on him as a child, and nobody knows what it stands for, but it’s the only name he goes by. So it’s not a name he was born with, but it’s his name by all given rights. And then there’s Ren, who is named for the beloved priest in the first series, so names can be an honorific in that way. The fact is we’re working in magical systems, and traditionally, in folklore for instance, names are very powerful entities. They become an object of possession. In this magical world, though we haven’t seen it depicted yet on the page, the concept is there that somebody could use your name to accomplish things, like the finding spell that uses a person’s hair. And so, when you don’t have much, it is something.

Names have power and the giving of names also has a huge amount of power, just as it does in our world. I think it was Holly Black who said, “if you want to write fantasy, what you actually have to nail is reality.” Fantasy is built on realism, so I try to make sure that when I’m asking questions about this magical world, I’m applying the same logic I would use in my real world. I use a lot of nature metaphors because when I’m asking the reader to take a departure from reality, it’s easier to do if the images they are holding in their head are things they can actually see, like a tree or a river. And I think our relationship to names is one of those things where I hug very close to how they operate in reality.

Chapter 16: Speaking of writing fantasy, I wonder how you feel about the classification of your work. Too often, genre works have been denied access to the larger canons they might naturally inhabit. For instance, you are a writer from the U.S. South, but because you write primarily fantasy, your work is not usually considered Southern literature. What parts of your work or practice can you point to as having roots in this part of the world even if the South doesn’t turn up in the frame of your narrative?

Schwab: It has still had a huge impact on me. My first novel was called The Near Witch, and it was about a tiny village and their relationship with strangers. Growing up in the South, there is that sense of the small town where, when something goes wrong, you don’t look to the people within your community for blame. You look for whoever doesn’t belong. A lot of my characters are outsiders, and some of them are born into a community they don’t feel at home in and others come into a community that does not welcome them. It’s more about the guards we put up around and within our community, the sense of familiarity and expectation of friendship and allegiance with our neighbors. Whether I’m writing about a small town in England or writing four interconnected worlds, I think about insider and outsider culture, and it all comes down to small-town mentalities.

Chapter 16: Something I would identify with Southern literature is the focus on place. You’ve got this sense of setting that is all-encompassing; you never forget where you are. And in this book, where you’ve got that movement between worlds, it’s even more important perhaps that a reader doesn’t lose that thread (pardon the pun) of each unique setting. Through it all, you cast a gorgeous atmosphere over this book, and perhaps it’s circumstantial, but it feels like autumn to me. For instance, when readers are first introduced to the Lightless Fair at the ice port, you write, “Good things have a way of growing. Now people come from all around and we look forward to the dark.” Is this a perfect book for the season when we might struggle against the increasing and early dark that comes with the shorter days?

Schwab: Oh, totally, 100%. It’s very October. I think all my books are fall books. When I say that, I think of the kind of books you want to take slowly. The kind of books where you want to create an environment that encourages you to disappear, whether that means curling up in a chair with a cup of coffee and a blanket or tucked in a corner of a coffee shop. There’s an intimacy to fall books. Fall books are meant to be enjoyed either in the comfort of your home or in a cozy space. My books have a soft voice, so I always think of them as being told to you at bedtime. I like to think of them as being read in a bay window that is just beginning to frost over.

Schwab: Oh, totally, 100%. It’s very October. I think all my books are fall books. When I say that, I think of the kind of books you want to take slowly. The kind of books where you want to create an environment that encourages you to disappear, whether that means curling up in a chair with a cup of coffee and a blanket or tucked in a corner of a coffee shop. There’s an intimacy to fall books. Fall books are meant to be enjoyed either in the comfort of your home or in a cozy space. My books have a soft voice, so I always think of them as being told to you at bedtime. I like to think of them as being read in a bay window that is just beginning to frost over.

But to your point about Southern literature, that is something else I’ve absolutely embodied — for me, place is a character. When I was writing Addie LaRue, which is set in so many places, I needed to be able to feel each of those places. I would go somewhere and ask myself: If you have one paragraph to describe this entire city, which details would you choose that a local would fault you for not including? Can I get it to a color palette, can I get it to a scent in the air? And I applied those same things to Red London and to White London. I want you to feel it. I want to be economical in prose, which is a funny thing to say about a 640-page book, but there is a lot of story to cover here! I want to see what is possible. It’s not just about conveying an act; it’s about conveying it efficiently. So what three details do we need when Lila gets off the ship and is standing on the ice? What are the three that will wrap themselves around the reader’s senses? I often rely on a food or a drink, so Tes drinks very strong black tea and eats dumplings, and these are things that readers can immediately taste or smell. Or the fairs will have intensely spiced foods, things that are savory and sweet at the same time, or that give you the sense of being elsewhere. Part of it is when I write, I see a movie in my head, down to where the camera angles should be, and my job as a writer is to write down the movie, so that the exact same film plays in your head, down to the score and the atmosphere and the angles.

Sara Beth West got fired from her first job. By her dad. Since then, she’s walked away from many other jobs, including nanny, retail worker, farmhand, choir director, teacher, social media manager, and compost truck driver. Most recently, she left a great job as a public librarian. But the one job that keeps following her around is writer. She writes book reviews and conducts author interviews for Shelf Awareness, Chapter 16, Southern Review of Books, and more. She lives in Chattanooga.