Loving the World More Fully

Margaret Renkl wants us to pay attention and stay hopeful

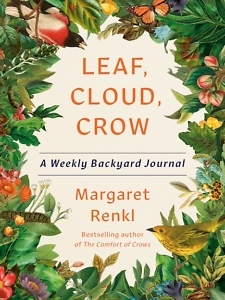

Perhaps Nashvillian Margaret Renkl needs no introduction, but with the selection of The Comfort of Crows as the 100th title in the wildly popular book club hosted by Reese Witherspoon, the spotlight is once again on Renkl’s unique blend of ferocity and tenderness. Her New York Times essays regularly remind readers of the crossroads encountered as we attempt to attend carefully to a world that can feel so tenuous.

For those trying to make a habit of paying such careful attention, perhaps Leaf, Cloud, Crow: A Weekly Backyard Journal can help. A companion to The Comfort of Crows, this journal is organized by season, encouraging readers to look closely at the plants and creatures that surround them, “to understand them more intimately, and to love them more fully.” Each week includes a short excerpt from The Comfort of Crows, a related prompt for reflection, and pages for recording thoughts, sketches, or any other moment of inspiration.

As with everything Renkl does, there is also an urging to do whatever you can to make a difference, a reminder that “change begins with looking directly at what’s happening. First love, then heartbreak, and finally action. And always, always hope.” She answered questions about Leaf, Cloud, Crow by email:

Chapter 16: Each week, your journal provides a prompt with lined pages for response as well as a blank page. Why was it important to include the blank page? How do you see these two elements working together?

Margaret Renkl: That was my brilliant editor’s idea. In fact, this whole journal was Joey McGarvey’s idea. We were quite far along in the process when she brought up the possibility of making the last page in each entry a place to add small drawings or paintings or collages, similar to the way the art exists in conversation with the words in The Comfort of Crows. That thought would never have occurred to me — my brother, Billy Renkl, got every shred of visual talent our gene pool has to offer — but I immediately saw the wisdom in Joey’s suggestion.

Unlike me, most people do have at least some facility with line and color. The urge to document the world, including our own place in it, can express itself in many forms. It’s possible to leave the blank page blank — or to use it for lists and graphs, or to keep writing — but taking the time to sketch what you’ve experienced is yet another way of slowing down and truly immersing yourself in the lived world. It’s also a way of teaching yourself to see in more detail.

Chapter 16: The introduction focuses on how we spend our time — whether “in buildings and cars” or “in a state of profound love for the natural world” — and offers this journal as a means to a “gift of time.” How does observing nature change your relationship with time?

Renkl: Back when I was a very young poet learning to scan metrical lines, it dawned on me that poetic meters are tuned to the human autonomic nervous system. You can feel the heartbeat of an iambic line. You can quite unconsciously time your breath or pace your stride to it. That’s one of the reasons why cultures without a written language so often convey history and stories in metrical forms: Words are just easier to remember and pass down the generations if they’re written in meter.

Renkl: Back when I was a very young poet learning to scan metrical lines, it dawned on me that poetic meters are tuned to the human autonomic nervous system. You can feel the heartbeat of an iambic line. You can quite unconsciously time your breath or pace your stride to it. That’s one of the reasons why cultures without a written language so often convey history and stories in metrical forms: Words are just easier to remember and pass down the generations if they’re written in meter.

So far as I know, at least, all the other earthly creatures still live in communion with their own biological rhythms and with the rhythms of nature, and so do people in developing nations: the vast majority of the living world, in other words. Here in the U.S., we mostly don’t. We live at the speed of the internet, at the speed of an automobile with a map app that pings when a state trooper is deploying a radar gun nearby. We live indoors, in climate-controlled rooms, and the way we live is destructive to both the planet and us.

Too many of us live with the pounding heartbeat and racing thoughts of constant, low-grade anxiety, as though being poisoned by adrenaline were a human being’s normal state. But when we put away our screens and move outdoors, when we sit still and listen to the birds in the trees — or in the sky, or on the sooty windowsills of city buildings, or in big-box parking lots — we seem to have no choice but to slow down. Time begins to pass at the speed of the Earth, not the speed of the internet. Muscles unclench. Heartbeats settle. Minds calm down and remember how to focus. Time slows.

Chapter 16: Noting the many heartbreaks that can come from paying attention, you insist on hope and the evergreen possibility of change. How might a practice of looking long at the world and reflecting ward off despair and generate change?

Renkl: I’m not totally sure it will for everyone, honestly, but it has always done so for me. To study the natural world is to learn that death is a part of life, that efforts aren’t always immediately rewarded, that tragedy can strike at any moment. But persistence is hard-wired into nature. If a house wren destroys the bluebirds’ nest, the bluebirds grieve — I’m convinced they grieve — but they also build a new nest. Not right away, and not always in the same spot, but they carry on. They try again. I take a lot of comfort from seeing some version of that persistence unfold in species after species. And season by season, of course, the cycle itself is a kind of persistence. “If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?” the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley asked. He knew the answer before he even asked it. We all do.

Chapter 16: This journal is a companion to your book The Comfort of Crows, and you quote from Ada Limón’s You Are Here, an amazing collection of poetry I’ve been enjoying this year and reviewed for Chapter 16. What other books or media would you suggest as cousins or companions to these?

Renkl: The Comfort of Crows is dense with epigraphs — more than 40 of them — but this time there was room for only one per season. I included so many epigraphs in the first place because I hoped that readers wanting to read more, to learn more, would follow those breadcrumbs to some nature writers who live in ecosystems that are very different from my own backyard in suburban Nashville.

Some books I especially admire in this context include Joanna Brichetto’s This Is How a Robin Drinks, Camille T. Dungy’s Soil, Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights, David George Haskell’s The Forest Unseen, Sue Hubbell’s A Country Year, Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s World of Wonders, and pretty much anything by Annie Dillard, Mary Oliver, or E.B. White.

Chapter 16: Last year, during a reading event for The Comfort of Crows, you described your motivation as a writer and public figure with the phrase, “not courage but cussedness,” a position I adore. What’s the distinction there for you?

Renkl: First, a caveat: I am not at all courageous. A truly courageous person may disagree with the distinction I’m making, but to me courage requires facing down calumny and danger without regard for the possibility of personal cost. Being a woman in any public role these days is always an invitation to calumny and sometimes to danger, but I try not to think about that. It does take a certain amount of cussedness to ignore the bullies, however, to keep talking when some people would prefer for you to shut up. Luckily, born-and-raised Southerners have a leg up in the cussedness department.

Sara Beth West is a librarian and a freelance writer focusing on book reviews and author interviews. In addition to Chapter 16, publications include Shelf Awareness, BookPage, Southern Review of Books, and more. She lives in Chattanooga.