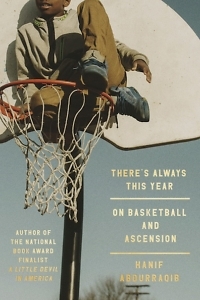

The Romance of the Game

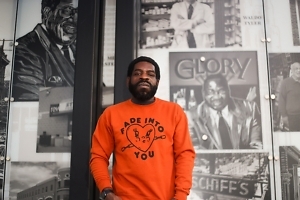

Hanif Abdurraqib meditates on the poetics of basketball and the streets of Ohio

With good books, you recommend titles to your friends; with great ones, you stop friends in hallways to read passages aloud. By that standard, Hanif Abdurraqib’s There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension is indisputably great. Books like this one perform that rarest of functions, not simply expanding readers’ minds but augmenting their mental repertoires. Abdurraqib captures the flickering moments when the eternal can be apprehended before it all recedes into chaos.

There’s Always This Year is a hybrid — part meditative essay on the poetics of basketball and part memoir of growing up in Columbus, Ohio, in the 1990s — that reads like prose poetry. Abdurraqib, recipient of a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant for verse and criticism, is at his best when he freezes a scene and expatiates on its manifold meanings. In one early passage (the “First Quarter,” as he puts it), he describes a game between Columbus’ Brookhaven High and Akron’s St. Vincent-St. Mary, a powerhouse led by LeBron James, already a national media superstar. Amid the back-and-forth struggle of the surprisingly competitive contest, Abdurraqib pauses to depict the signature shot of Brookhaven’s star player, the five-foot-seven Andrew Lavender.

“The floater, the most romantic shot in the game when done right, guided toward the rim with a heave and a wish, how the follow-through after the ball leaves the hand can look like an overeager wave, like saying goodbye to a person you never wanted to leave,” Abdurraqib writes. The floater “turns the ball into a bit of a show-off, obsessed with drama, almost pausing in the air to make sure you get its good side before it begins to twirl downward.”

When he’s not illuminating the game’s aesthetics, Abdurraqib explores the semiotics of basketball, analyzing how court images accrue cultural meanings. Though he feels a native Ohioan’s distaste for Michigan, he loved the Wolverines’ Fab Five from the early ‘90s, particularly a photo of the stars as freshmen, unsmiling. “[T]here they do not look bereft of joy,” Abdurraqib says. “They look mostly like teenagers. Certain of their invincibility.”

Abdurraqib becomes rapturous recounting Michael Jordan’s first NBA dunk contest, before the championships and the baldness and the “Be Like Mike” Gatorade campaigns. “Mike was never as cool as he was when he climbed toward the sky with two gold chains around his neck, ascending, too, so there could be no mistake about that miraculous air that refused to let MJ down,” Abdurraqib writes. “Even now I wish to touch the hem of that type of cool. To ascend and then return, knowing the world has been altered before I landed.”

Abdurraqib becomes rapturous recounting Michael Jordan’s first NBA dunk contest, before the championships and the baldness and the “Be Like Mike” Gatorade campaigns. “Mike was never as cool as he was when he climbed toward the sky with two gold chains around his neck, ascending, too, so there could be no mistake about that miraculous air that refused to let MJ down,” Abdurraqib writes. “Even now I wish to touch the hem of that type of cool. To ascend and then return, knowing the world has been altered before I landed.”

The hoops that Abdurraqib encounters on the streets and in the gyms of Columbus provide evocative metonymies for the character of its citizens. He reminds readers of the region’s economic depression and recurrent tragedies but devotes more space to its local legends. He recalls Kenny Gregory, a hero from his block, going to the McDonald’s All-American Game and winning the dunk contest with a feat verging on the Jordanesque. “Kenny was in the air long enough for everyone crammed in a small East Columbus living room to rise to their feet in anticipation,” Abdurraqib says. “Long enough for an entire neighborhood to hold its breath.”

The fact that Kenny Gregory didn’t go on to have a notable NBA career doesn’t diminish Abdurraqib’s esteem. He recounts the stories of several Ohio players who, for reasons unrelated to their athletic skill, never reach the plateau where the game’s legends roam. But that doesn’t make them failures; as Abdurraqib attests, they achieved mythical greatness, even if it never resulted in ESPN fame or million-dollar contracts: “[I]t might do all of us some good to reconsider what making it even means, or at least to honor a world where making it is not defined by the glamorous exit, not only by television cameras.” He knows what he’s witnessed in Columbus. “In my head, we got a hall of fame that might run the best five from wherever you’re from off any court,” he boasts.

There’s Always This Year pays special attention to the career of LeBron James, an Ohio native who as a member of the Cleveland Cavaliers galvanized the region and then broke its heart by going to Miami, spurring outrage, including riots where lovelorn fans set fire to LeBron’s Cleveland jersey. Those same fans — who, Abdurraqib notes, were all white — reversed their rhetoric when LeBron returned to the Cavaliers, and they danced in the streets when he brought them the longed-for championship.

Readers may extrapolate life lessons from this book, but what makes it entertaining for basketball fans is its relentlessly hoops-centric view of the world. Each “ascension” in this memorable book is by its nature short-lived, but also well earned. Long after our return, we remember what it was like to fly.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.