Hunger and Awe

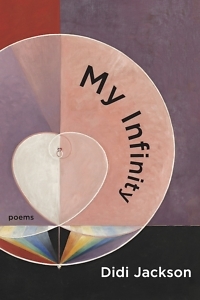

Didi Jackson merges the sacred with the natural world in My Infinity

Didi Jackson’s luminous new collection, My Infinity, opens with a poem titled “Witness,” signaling the fiercely attentive series of observations to come. In the poem, set on a lush day in Vermont’s Green Mountains, the leaves on the birch trees surrounding the speaker “clap at the sun with their gilded hands … these trees too raise their open palms / to pray.”

These mountains “must know // summer is closing,” the speaker realizes. “It is their secret; / I am good with secrets.”

Another early poem, “Awe,” provides a different kind of personal invocation, directing us to notice darker and stranger occurrences in the natural world, when mortality seems ever-present: “In these moments, I need to know / why the Luna moth has no mouth, // or if it was a sapsucker not a downy woodpecker / half decayed on the street near the elm. / For I too have held the dead in my bare hands.”

But the poem ends on a striking note that initiates us into the book’s fusion of the material and spiritual worlds: “I want / to bury all that I find with my hunger and awe.”

This collection follows Jackson’s debut, 2020’s Moon Jar. Now, My Infinity deepens Jackson’s already memorable explorations of grief and nature through a rich companionship with the work and life of visionary Swedish painter and mystic Hilma af Klint. In these poems, Jackson, who currently teaches writing at Vanderbilt University, finds elegant expression for the complex interdependence between the outer world and our myriad inner worlds.

Hilma af Klint, whose innovative works may be the earliest known examples of modern abstract painting, worked in obscurity, steeped in the spiritualist movement well known at the time. She helped to form The Five, a small group of women artists who experimented in trance and automatic drawing and channeled instruction from spiritual beings they called High Masters. As depicted by Jackson, af Klint’s perspective — “her wind chime mind reaching the between” — prizes receptivity and abundance as it evolves to include new shapes, lines, and subjects.

Born in 1862, af Klint displayed exceptional insight into how painting, physics, botany, and her own mystical cosmology could fuse and transmute into new forms so disruptive to the received ideas of her time that she left instructions for most of her work to be held back from the public until decades after her death, when society would be ready to embrace it.

Born in 1862, af Klint displayed exceptional insight into how painting, physics, botany, and her own mystical cosmology could fuse and transmute into new forms so disruptive to the received ideas of her time that she left instructions for most of her work to be held back from the public until decades after her death, when society would be ready to embrace it.

Remarkably, that’s what happened. During the past decade, af Klint has blazed into art history on the strength of exhibitions like 2018’s recording-setting Guggenheim Museum show, “Paintings for the Future.” Her vision found its way beyond death, just as she foresaw. Af Klint’s work contains a fascinating interplay between hiddenness and exposure — the profound need to communicate a grand communal vision and the intensity of private revelation and underground germination, waiting for the season to turn.

Jackson writes deftly insightful ekphrastic poems that engage several of af Klint’s painting series, including “Primordial Chaos,” “Eros,” “The Swan,” and perhaps her best-known series, “The Ten Largest,” which depicts an entire lifecycle — childhood, youth, adulthood, and old age — in bold abstract forms. Jackson chooses one painting from each category, and these poems are perhaps the most energetic and seamlessly written of her af Klint poems.

Jackson also writes about af Klint’s automatic writing (“I pounded on the door // to unlock another reality.”), her especially memorable painting “The Tree of Knowledge,” and the intimate dynamic she shared with the other members of The Five.

The poems of My Infinity must also reckon with the death of their speaker’s first husband. “After My Husband’s Suicide I Visited a Psychic in Cassadaga, Florida” recounts a disappointing attempt to locate “a way / into the dark, // an escape hatch from this world / toward his spirit, a handle // to pull that might open / a trap door into eternity.” “Two-headed Woman” imagines poet Lucille Clifton moving her fingers across a Ouija board. These poems also offer links to af Klint’s encounters with the High Masters.

Grief is a mobius. And so are the innumerable cycles of loss and replenishment that power the natural world, from the unfathomable cosmic-sized blasts that birth new galaxies to the infinitesimally tiny and complex acts of cellular birth and death that make up the human eye’s ability to perceive light and color.

Several poems refer to the speaker’s recurrent painful experiences with migraines — an affliction sometimes linked with mystical visions. Jackson describes flinching as bright light “shatters / into murderous cracks and angles, / vibrating metal shards, chromatic devils / from beyond.” Still, such visions can provide a dark but potent road to illumination — “an abstract pageant of pain, a prism / of colors as sharp as any knife.”

In these poems, nature reminds us of our deeply ingrained drive toward newness, however marbled by losses or fears. In “Fall,” the speaker declares that “it is the darkest days / I’ve learned to praise.” Moments like these, which exist on thresholds of potent change or revelation, occur again and again throughout My Infinity.

In the final poem, “Mercy,” the speaker recalls cherished sensory impressions — “the charred smell of old fire rings,” “the kingfisher’s rattle at the water’s edge” — but recognizes her own perspective’s limits to perceive or understand any realm beyond these observations: “How do I pray / to anything larger than this? Everything / is of me and so much greater / than me.”

Reading poetry often feels like a dance between abstraction and specificity. This internal tension makes Hilma af Klint an especially satisfying presence in My Infinity. Af Klint once wrote that, to make her best work, “I have been forced to renounce the dearest wish of my youth: to be able to reproduce outer form and color.” Instead, she went inward — profoundly inward — in order to discover forms that reflected the mystical intimations which formed the deepest impetus for her life’s work.

Fueled by explorations of af Klint’s life and vision, Jackson’s world brims with danger and ecstasy. The poems of My Infinity thrive at points of threshold, unafraid of paradox and ambiguity. These poems press into liminal moments, creating spaces for illumination and astonishment.

[Read a poem from My Infinity here.]

Emily Choate is the fiction editor of Peauxdunque Review and holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Her fiction and essays have appeared in Mississippi Review, storySouth, Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Rappahannock Review, Atticus Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and elsewhere. She lives near Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.