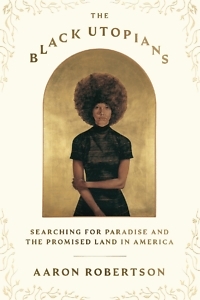

American Dreams

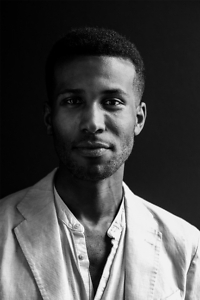

Aaron Robertson weaves personal and political history in The Black Utopians

The iconoclastic Harvard law professor Randall Kennedy once posited that Black intellectual history is best understood as a tug-of-war between optimists and pessimists: those like Dr. King and Barack Obama who preached hope for racial reconciliation and those such as Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael who eschewed it. (Some pessimists, according to Kennedy, switched sides — think Frederick Douglass — and other optimists turned to pessimism, like W.E.B. du Bois.)

Aaron Robertson’s exacting, poetic The Black Utopians tracks the rise of Black nationalism, skeptical to its core, through a cadre of Detroit activists, knitting their creative and often militant ideas with memoir and his formerly incarcerated father’s letters, centering the question: “What does utopia look like in black?” The book is a marvel of storytelling.

A Detroit native, Robertson spent summer vacations in Promise Land, Tennessee, a Dickson County enclave of African American farmers and small business owners. Amid “the August heat, the chattering cicadas, the ticks hiding in underbrush,” he reveled in a nurturing community that dated back to Reconstruction, seeding his future research into Albert Cleage, Jr., a feisty Detroit pastor who seized the possibilities of justice by advocating for separation. Robertson crafts The Black Utopians around Cleage and magnetic figures such as the painter and criminal Glanton Dowdell. The author excavates fresh nuggets from the well-trod terrain of the Civil Rights era. His depiction of engagement among Detroit’s Black congregations is textured and engrossing; he unearths class tensions and rivalries that fueled the liberation movement.

Cleage, who was raised in an aspirational, proper family, broke with the peaceful rebellions of Dr. King and his colleagues: a weak tea, in his view. He preferred an explicit confrontation with the scourge of white supremacy. Dispirited by accommodating clergy, Cleage founded the Shrine of the Black Madonna, which morphed into a broad enterprise, with cultural satellites in Kalamazoo and the South. “The Shrine of the Black Madonna was to be more than a church. It would be a laboratory for social experiments, open to all who supported black liberation, starting in a maligned, dream-filled city,” Robertson writes. “The black revolution was not only about tearing things down, or building things up, or letting their hair fly free. It carried within it the wisdom of the divine spirit that moved through each of them, convincing them they were holy because they were common, earthbound.”

In 1967, riots upped the ante in Detroit, cleaving not just white and Black but also moderates and leftists. Although more sinner than saint, Dowdell rigged his own platform; he sketched and painted in prison, stirring interest in his talent, which spread after his release. He sought asylum in Sweden while being investigated for bond forgery — somehow, he’d beaten a murder rap — and became a cause célèbre in Stockholm. Robertson intersperses these less-famous stories with his father’s epistolary account of his life while incarcerated, the scales of justice and morality tipped against him. Doe Robertson’s fierce longing to connect with his child — and to pursue that most American and tenuous of dreams, personal liberty — add a beautiful poignancy to the history Robertson crafts here.

In 1967, riots upped the ante in Detroit, cleaving not just white and Black but also moderates and leftists. Although more sinner than saint, Dowdell rigged his own platform; he sketched and painted in prison, stirring interest in his talent, which spread after his release. He sought asylum in Sweden while being investigated for bond forgery — somehow, he’d beaten a murder rap — and became a cause célèbre in Stockholm. Robertson intersperses these less-famous stories with his father’s epistolary account of his life while incarcerated, the scales of justice and morality tipped against him. Doe Robertson’s fierce longing to connect with his child — and to pursue that most American and tenuous of dreams, personal liberty — add a beautiful poignancy to the history Robertson crafts here.

Robertson conjures the cultural ferment of the 1970s, with glimpses of Amiri Baraka and Muhammad Ali; a sprig of radical chic flavors The Black Utopians’ consequential themes. The latter chapters skew toward Cleage, who’d renamed himself Jaramogi Agyeman, and the desire for separation that led him to invest in Beulah Land, a South Carolina farm isolated from institutionalized bigotry. Jaramogi envisioned a kind of Black homeland embedded in the South: autonomous, communal, inflected with values born of suffering and resilience. After his death in 2000, the Shrine’s influence and income tapered off. Beulah Land never flourished according to plan.

Robertson weaves together his narrative strands as he limns his own reckoning with racial ostracism, how the deck is forever stacked against those who need change — sweeping change — now. “New prisons were being built across the country” at the turn of the new millennium, he notes. “Unions were disappearing. Police brutality and gerrymandering persisted. Black preachers had lost their way by shouting the gospel of prosperity.” Such decay brings us to our fraught moment, which he attributes to a collective failure of imagination and the erosion of E Pluribus Unum, the concept of a pluralistic republic long past its sell date, or at least overtaken by events.

Hamilton Cain is the author of This Boy’s Faith: Notes from a Southern Baptist Upbringing and a frequent reviewer for a range of publications, including The New York Times Book Review, The Washington Post, and The Boston Globe. A native of Chattanooga, he lives in Brooklyn, New York.