Safety Without Violence

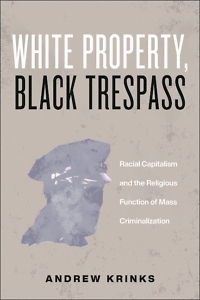

Nashvillian Andrew Krinks turns a spiritual lens on race and mass incarceration

I first met Andrew Krinks when he was an undergraduate at Lipscomb University. He was part of a loose community of folks committed to friendship and solidarity with one another despite the fact of incarceration: a mix of students, scholars, lawyers, caged and uncaged. Among them were Cyntoia Brown, Rahim Buford, Harmon Wray, Janet Wolf, Richard Goode, Preston Shipp, Jeannie Alexander, and Andrew’s partner, Lindsey Krinks. Stumbling into this particular iteration of beloved community in Nashville was transformative for me. Before I knew it, I was headed to Atlanta to see Radiohead with Andrew and Lindsey and our mutual friend, Geoff Little.

All along, Andrew has struck me as the best kind of scholar activist. Whether offering instruction through a megaphone at a demonstration, a poetry workshop at the Tennessee Prison for Women, or in classrooms at TSU or Vanderbilt, he appeals to people’s conscience and creativity with his own. He is also a phenomenal writer who fears no data. He knows that healing requires acknowledging difficult data. Like James Baldwin, he understands that not everything we face can be changed, but nothing can be changed until we face it.

Andrew’s book White Property, Black Trespass examines mass incarceration and racial hierarchies through a spiritual lens, with a perspective rooted in the belief that “there is life beyond the present order of exploitation, dispossession, and death.” He answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: You dare to speak of whiteness — and of whiteness as a religion — and you also do us the great and risky kindness of saying how you yourself understand that clinging to “racial, gender, and class inheritances” as a means to wholeness is “spiritual death.” Could you say more about how whiteness is a religion and how clinging to it is a form of death?

Andrew Krinks: I understand religion as the myriad ways that humans attempt to transcend, transform, and make ultimate meaning of the conditions of mortal finitude. People navigate and make sense of the human condition in quite different ways. This is why religion is and always has been many things, including both life-giving and death-making.

Death-making religion happens when people seek to escape the limits of finitude and the inevitability of death by reducing others to states of vulnerability to premature death, which provides a sense of godlike power and control, illusory as it may be. A violent mythology — what Baldwin called a “genocidal lie”: This is the story of whiteness.

So how, specifically, is whiteness a religion? Whiteness constitutes a religion, first, because it came into being as an inhabitable idea in and through the theological reasoning and violent acts of dispossession carried out by early European Christian colonizers and capitalists. There was no such thing as “white people” before about 1700. There were English, French, Dutch, German, and other people of European descent, but there was no such thing as a consolidated “white” identity. That changed through the aspirations of European Christian men of property to become like God in relation to people and planet: transcendent, invulnerable, omnipotent, and so on. As W.E.B. Du Bois put it, whiteness is a possessive power of godlike proportions: “Ownership of the earth forever and ever, Amen!” Whiteness is a religion because it is a means by which a group of people get to be as powerful as gods. And for one group of humans to function as God, many others must be defined as not God, or distant from God, which often becomes the basis for their outright destruction.

Whiteness came into existence when European men of property defined themselves in absolute opposition to all others. This is why I understand whiteness as a pursuit of self-deification that ultimately results in self-debasement instead. It is an attempt to escape the world on the bent backs of those it sacrifices in pursuit of its transcendent power. Believing itself to be above and apart from all others, whiteness is an embodied aspiration to escape the kinds of mutual relation with people and planet that in fact sustain us. Absolute independence rooted in existential fear of mutuality with others is spiritual death.

Chapter 16: What words might you have for the white person who beholds your title and feels doomed?

Krinks: I don’t believe that guilt motivates the kind of action needed to transform our world. So I’m not interested in making white people — myself included — feel bad as individuals for inheriting what amounts to a curse. I’m more interested in inviting people to locate pathways to a personhood beyond the confines of spiritual death, a personhood based on the truth that Fannie Lou Hamer and others named when they said that none of us are free until all of us are free.

I also go to great lengths in the book to make the case that “whiteness” and “white people,” as I understand them, are not exactly synonymous. Whiteness is a power, a force, an inhabitation through which people of European descent are invited to imagine themselves as inherently moral and proximate to — even resembling — God. People who are not typically understood to be “white,” however, can also aspire to and in some cases be partially welcomed into whiteness. Meanwhile, “white” people who either fail to live up to the propertied and patriarchal standards of whiteness or who fail to faithfully embrace their whiteness by refusing to demonize nonwhite people – what earlier generations called “race traitors” – are often treated as undeserving of their whiteness and are thus discerned as more closely resembling their nonwhite counterparts.

I hope that by clarifying the deadly origins and function of whiteness, including the false promises it makes to those who inhabit it, the book, when read with curiosity and care, actually invites “white folks” to find hope for life beyond the spiritual death of whiteness in its pages.

Chapter 16: I’m inspired by this saying of yours: “In order to build what could be, we must more fully understand what is.” I voice it as a preface when I share your claim that mass incarceration is actually mass criminalization is actually a taxpayer-funded religious commitment. That claim is hard to unsee once you tie our so-called criminal justice system to the Doctrine of Discovery. What is the Doctrine of Discovery and … is it still on the books?

Krinks: One of the primary intentions of my book is to show the inextricable connections between a fundamental religiosity of racial formation, property possession, and the capture and caging of human beings in the name of “safety” and “justice.” Historically speaking, whiteness was first articulated in relation to acts of exclusive possession — absolutely exclusive private property — which always entails dispossession, a life-disrupting act of displacement. And as I show in the book, these eurochristian acts of displacement were often explicitly justified through interpretations of Jewish and Christian sacred texts.

Krinks: One of the primary intentions of my book is to show the inextricable connections between a fundamental religiosity of racial formation, property possession, and the capture and caging of human beings in the name of “safety” and “justice.” Historically speaking, whiteness was first articulated in relation to acts of exclusive possession — absolutely exclusive private property — which always entails dispossession, a life-disrupting act of displacement. And as I show in the book, these eurochristian acts of displacement were often explicitly justified through interpretations of Jewish and Christian sacred texts.

The Doctrine of Discovery — the idea that God invites people of European descent to conquer Indigenous people’s lands — and later John Locke’s rationalization of private possession as obedience to a God who commands humans to “subdue” the Earth led to incalculable levels of displacement and death over the course of centuries, both in Europe and on Turtle Island. These religious and political doctrines are an integral part of the origin story of European colonialism and racial capitalism, which means they are integral to the foundation of the “nation” in which we live.

So what do criminalization and incarceration have to do with this history? Many of the tens of thousands of people displaced from commonly tenured lands in England a few centuries ago — a displacement justified by religious ideas and enforced by police — found themselves subject to labor and vagrancy laws that criminalized the refusal to be properly subject to capital, to labor to create wealth for someone else. For centuries, those so criminalized were brutally tortured or even executed in public, often with clergy leading the procession. When the state moved away from public torture and execution for people’s state of dispossession, it transitioned toward what would eventually become the modern prison. The first prisons were full of poor folks. Very little has changed since then.

The religious doctrines that sacralize acts of possession and dispossession and human sacrifice in the form of human caging remain with us, if not by the letter of the law, then by its spirit. Cops murdered George Floyd because he trespassed against the order of capital — he allegedly used a counterfeit twenty. Cops in Louisville, in coordination with propertied interests, targeted a property with which Breonna Taylor was associated, criminalizing low-level offenses there in order to justify evictions and thereby make way for the displacing forces of gentrification, which disposed cops to approach Taylor’s door in the mortally violent way they did. And just like the proto-police forces who forced poor folks off land in rural England a few centuries ago, police in Nashville and other cities today continue to serve as the foot soldiers of racial capital — real estate and corporate power — by criminalizing and removing poor and unhoused folks off land that they do not properly “own.”

If we don’t reckon with these histories of the present, and particularly the role of religious ideas and practices in creating them, it will be hard to build anything different to replace them.

Chapter 16: You’re inviting Americans to love themselves and others more by being more — not less — realistic about harm reduction. You propose data-driven approaches to harm which “refuse to eliminate people who have hurt others, recognizing that everyone who hurts someone in a significant, life-altering way are themselves survivors of some significant harm.” How did you arrive at this recognition?

Krinks: I arrived at this first through relationship with criminalized and incarcerated people, which began for me about 15 years ago. Many of the incarcerated people I have known often say that “hurt people hurt people.” It’s an expression of the understanding that violence and harm are cyclical. There is endless research showing that the vast majority of people who end up in prison are survivors of violence and usually of poverty as well. And instead of intervening to disrupt cycles of violence by meeting people’s basic human and emotional needs and asking serious questions about why a given harm happens in the first place, we send in violence workers — police, prosecutors, wardens, corrections officers. Police and prisons are definitionally incapable of disrupting violence, because police and prisons are explicitly based on the use of violence.

I also learned these lessons from writers and practitioners of restorative and transformative justice, including Danielle Sered, who wrote a line that I have repeated more times than I can count: “If incarceration worked to secure safety, we would be the safest nation in all of human history.” Clearly, we are not. One of the most dangerous myths that we live by is that police and prisons exist to keep us safe and that they are successful in that mission. Police and prisons came into existence to create and maintain hierarchical social order — which is always an extension of what I call “sacred order” — not to keep us all safe, nor to provide thoroughgoing “accountability,” nor to meet the complex needs of survivors. If these institutions really want to insist that they are trying to do these things, then we must conclude that they are failing massively.

Meanwhile, the mythology that capturing and caging millions of people every year makes us safer persists, and we are all far less safe as a result. Another of the primary intentions of my book is to contribute to the work of breaking the link in our imaginations between criminalization and safety. As an abolitionist, I want more safety than we currently have, not less, and that is why I write and organize for a future freed from the illusion that state violence saves us.

Chapter 16: I love the way you frame “noncarceral modes of accountability” as ancient and also ascendant. How is it that so many of us lose sight of this fact and somehow imagine creatively nonviolent responses to hurt and harm as rare?

Krinks: One of the greatest insights I have gained from present-day abolitionists — those who believe that the way to authentic safety is by meeting all people’s most basic needs and preventing and responding to harm in ways that break the cycles that first generated the harm and that strive for as much repair as possible in its wake – is that we already know how to create safety and accountability beyond police and prisons because we already practice it in a variety of ways.

If we have ever accompanied a friend navigating emotional trauma or mental illness, talked to a neighbor whose music was too loud, talked someone down from verbal or physical retaliation after being hurt, helped someone identify and locate a community resource, provided presence to a child as they navigated big feelings that wanted to find expression in harmful ways, checked on a neighbor who seemed to be struggling, or apologized to a partner for saying or doing something harmful, then we already know some of the essential ingredients of safety that don’t resort to violence.

There are people in our community who have also trained themselves up in the ways of restorative and transformative justice that are creating paths to accountability without human disposal. I have personally benefited from their interventions. Moreover, if the work of making police and prisons obsolete includes meeting people’s most basic needs on the front end — rather than waiting until their precarity leads to harm and then responding on the back end – then anyone who has contributed anything to creating more affordable housing, healthcare, education, transit, libraries, community centers, youth services, and other public goods has contributed to the possibility of a world on the other side of violent responses to the many social problem we face.

I believe that we lose sight of these things — or are prevented from perceiving them in the first place — because the social order we live in depends upon our devotion to “public safety” in the form of state violence to maintain the hierarchies that grant power and wealth to a few while subjecting many to perpetual vulnerability. We seldom recognize there are other ways because the powers that be recognize that investing more in non-police, non-carceral modes of safety and accountability also entails divesting from the forces that maintain the hierarchical order of things. People with a lot of power and wealth do whatever they can to protect and fund police because police are essential to the task of maintaining their power and wealth.

In the end, if it’s a kind of faith that believes that police and prisons keep us safe — that they, in some sense, save us — then we need another kind of faith that believes in the possibility that we can actually attain greater safety and collective thriving than we currently experience. Many of our formal faith traditions provide resources in pursuit of such a world, including those traditions that are also complicit with the creation of the institutions that have wrought so much pain. But folks don’t have to claim a formal religious tradition to join a movement guided by embodied faith that “another world is possible.” There are thousands of people and dozens of organizations in Nashville engaged in this work. I hope folks will seek and find them.

David Dark is the author of six books, including The Possibility of America, Life’s Too Short to Pretend You’re Not Religious, and We Become What We Normalize. He lives in Nashville and teaches at Belmont University and the Tennessee Prison for Women.