In the Drink

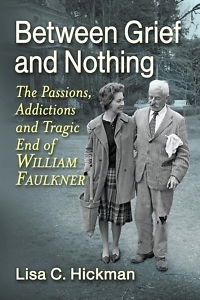

Lisa C. Hickman’s Between Grief and Nothing chronicles William Faulkner as a man set on his own destruction

Hear the name William Faulkner and you think of his work. Short stories like “Barn Burning” or long ones like “The Bear,” such novels as The Sound and the Fury or Absalom, Absalom! The tangled prose, those thorny truths. And his greatest creation, a small world as real to us as the dirt under our feet, the mythical Yoknapatawpha County.

Yet the work wasn’t enough. It never is. When we’re fascinated by the art, we must find out all we can of the artist. So we know Faulkner the man, deeply flawed and self-destructive. Conductor of his own doom. That’s the one author Lisa C. Hickman chronicles, with painful detail and almost clinical attention, in Between Grief and Nothing.

This Faulkner drank not just to excess but to oblivion. He tortured his body, falling down steps while bingeing or off horses even more obstinate than him. He carried on affairs that damaged an already fraught marriage with his wife Estelle.

They had barely wed when she began to wonder what she’d gotten herself into. His “brooding silences.” His haphazard grooming. His single-minded focus on his work — it was 1929 and he was reading proofs of The Sound and the Fury — rather than his new wife, even as they were celebrating their nuptials with a trip to Pascagoula, down on the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

Estelle was already feeling neglected, wondering whether life with a “creative genius” was for her:

One night after admittedly too much liquor, she simply walked into the water in a silk gown. Had Bill not called out and a neighbor rushed in to rescue her, she might have quietly slipped away …

Other than that, Mrs. Faulkner, how was the honeymoon?

And so it went, the life, strife and troubled times of a literary giant who was — despite the string of classics that included Light in August and As I Lay Dying, despite the Nobel Prize and world acclaim — all too human.

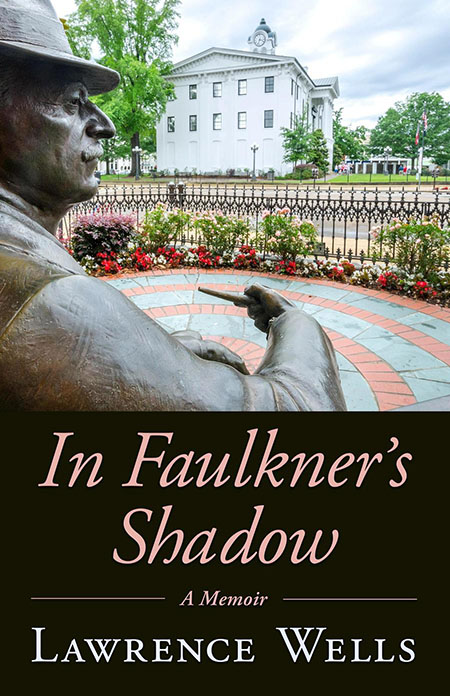

You may have visited Rowan Oak, Faulkner’s Greek Revival-style home in Oxford, Mississippi, with its cedar-lined walkway and the outline for the novel A Fable written on his office walls. You may have felt closer, somehow, to the great author, maybe even sensed his ghost, there at the typewriter, pecking out a new tale of some Snopes up to no good.

You may have visited Rowan Oak, Faulkner’s Greek Revival-style home in Oxford, Mississippi, with its cedar-lined walkway and the outline for the novel A Fable written on his office walls. You may have felt closer, somehow, to the great author, maybe even sensed his ghost, there at the typewriter, pecking out a new tale of some Snopes up to no good.

In Hickman’s book, Rowan Oak is occasionally that place of calm and creativity, the refuge from the prying world that the private and notoriously shy Faulkner so badly needed. But too often, it’s a place of seething and rancor, of “often volcanic” domestic scenes.

Hickman also takes us to another Faulkner landmark, 46 miles away in Byhalia, Mississippi: the Leonard Wright Sanatorium, where Faulkner (and Estelle, who likewise had trouble with drink) and other well-heeled or prominent Mid-Southerners went to dry out. It’s also where Faulkner died, at 64, on July 6, 1962.

The chapter on Wright’s is fascinating, not just because of the Faulkner connection. It’s a well-drawn portrait, a “story of time and place,” as Hickman writes. “The Old Country Club,” as it was known, was “a quiet, bucolic retreat,” and rather than “evoking any kind of social stigma, staying at Wright’s was a status symbol of sorts.” But the idyllic setting belied the darker purpose. The “guests” were addicted to drink or drugs and could be dangers to themselves and others.

Hickman writes that Faulkner’s affairs “seemingly were another form of addiction,” and it appears so. There’s much here about his liaisons with Meta Carpenter, a fellow Southerner he met during a script-writing stint in Hollywood, and Joan Williams, an aspiring writer from Memphis who was some three decades younger than Faulkner. All the while, Faulkner and Estelle remained married, mostly unhappily so.

Maybe it’s unnecessary to say this now, but: Reader beware. If you love Faulkner’s novels and stories, if he’s your literary ideal, this is a tough read. This isn’t the writerly Faulkner, the artist of immense power and vision. This is Faulkner the drunk, who can’t get out of his own way. As for the “passions” of the subtitle, they’re more sad than anything else. Shameful, too, the way Faulkner carried on — or tried to — with a woman closer to his daughter’s age.

Should you read it? Faulkner — who famously in a 1949 letter suggested his own epitaph: “He made the books and he died” — would have said no. Well, then he should have behaved himself better.

Between Grief and Nothing, painful as it can be to read, is a worthy addition to the study of all things Faulkner. It connects dots, provides depth and shading to a complex life. It doesn’t crack the mystery that was the man — that’s impossible — but we come to understand him at least a little more.

Hickman’s book does something else — and it’s a good thing. It makes you marvel, more than ever, at how such a troubled soul wrote so much, and so well, for so long — the best body of work, surely, in American literary history.

Or, to put it another way: He made the books and they’ll live forever.

David Wesley Williams is the author the forthcoming novel Come Again No More (JackLeg Press, 2025), as well as the novels Everybody Knows (JackLeg Press, 2023) and Long Gone Daddies (John F. Blair, 2013). He lives in Memphis.