“I Can’t Tell a Story”

Poet Charles Wright reflects on his life and work in a lively 2017 interview

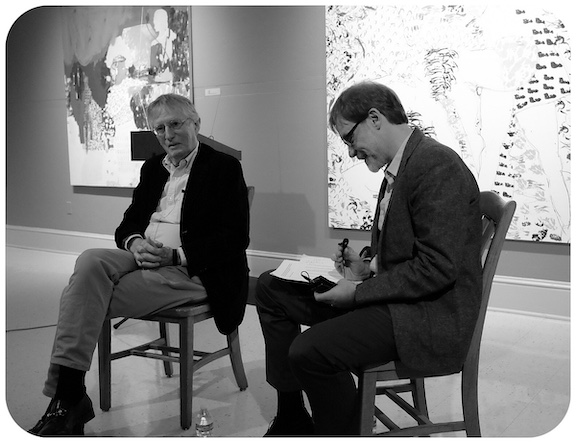

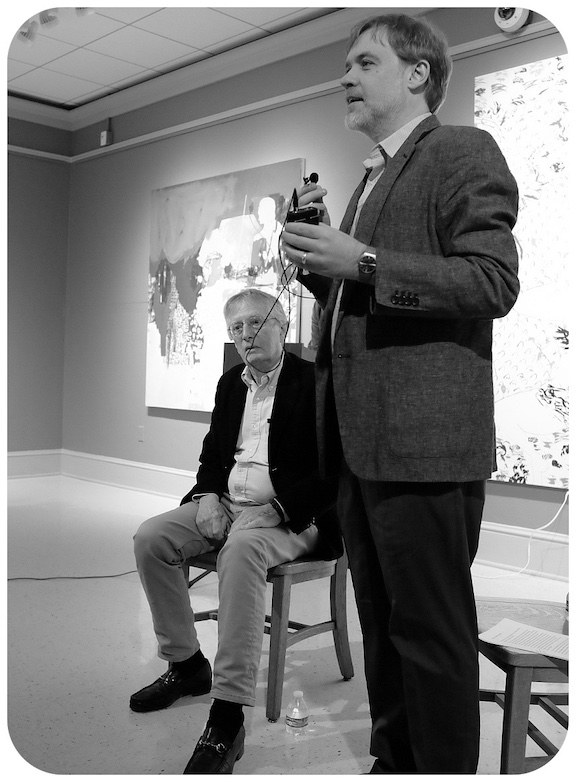

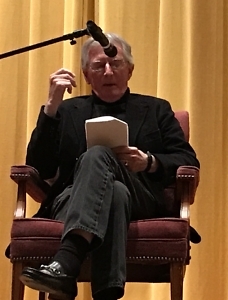

Charles Wright, former U.S. Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize-winner, visited East Tennessee State University on October 25, 2017, to read his poems and meet our students and community here in Johnson City. This had been a dream of mine since I met Charles at the University of Tennessee, when I was a graduate student, and he had been so generous to me later as I worked on editing poetry anthologies. His poems meant so much to me, in bringing an experience of eastern Tennessee into conversation with the great art and literature of the world. I wanted my own students to share in that feeling, though I knew that Charles was not doing many public events anymore.

My friend and colleague, Dr. Scott Honeycutt, had recently led an initiative to have a plaque dedicated to Charles at the Kingsport Public Library, and we devised the plan to offer to handle all the transportation if Charles came to ETSU. What followed was certainly the most fun literary road trip of my life, as Scott and I drove to Charlottesville to pick Charles up and bring him to Johnson City, and then take him home two days later. On the way back, we took Charles to see the plaque and to visit his childhood home in Kingsport. His conversation was so rich and enjoyable that Scott and I made a private list of “Charles Wright-isms.”

In the years since, we have been fortunate at ETSU to host such luminaries as Joy Harjo, Natasha Trethewey, Rita Dove, and Nikki Giovanni, and in the months ahead, Li-Young Lee and Ron Rash will visit us. Charles Wright’s appearance was special, though, because he spent most of his childhood and teenage years just a few miles up the road in Kingsport. The feeling among the audience was that a local hero had come home, and what an audience it was. We had hundreds of people in attendance for the interview and the evening poetry reading, far beyond our best expectations. The local TV news team unexpectedly appeared. We had to turn away a class of high school students from the University School on campus because there was no more space in the Reece Museum, and that evening, people were sitting in the aisles of our auditorium because all the seats were filled. I overheard Dr. Bert C. Bach, ETSU’s provost and vice president of academic affairs, say to his friends Flora and Henry Joy, “We had better hurry up and get the football stadium built, so we will have space for our poetry readings!” We brought a bit of magic down from the air in October of 2017, and I hope that Charles Wright’s good humor and lightness of spirit from that day come through in our conversation.

This interview was conducted by Jesse Graves with former U.S. Poet Laureate Charles Wright on October 25th, 2017, in the Reece Museum at East Tennessee State University. The interview was recorded by Adam Timbs and transcribed by Harley Mercadal, both ETSU graduate students at that time, and lightly edited by Graves and Wright. It is published here for the first time in honor of Charles Wright’s 90th birthday, August 25, 2025.

Jesse Graves: Hello, Charles, welcome back to East Tennessee. I hope we can make this a happy homecoming for you. Will you tell us about the role East Tennessee, and the other places of your childhood, have played in your poems? It seems that you had a great career taking shape in California, teaching at UC-Irvine, living near the beach, publishing your poems in prestigious places. What drew you to Virginia at that time, and back to the South?

Charles Wright: It’s good to be back in East Tennessee, which I haven’t visited for many years. I got drawn back to the South by the University of Virginia — the Harvard of the South. Well, I got disabused of that idea after 27 years of teaching there (laughter). But it’s still a good place, you know. I don’t know why I came back. My wife had grown up in Los Angeles, and my son had turned 13 just as Laguna Beach was heading into the drug problem, as every place else in California was, so we decided to come to Charlottesville. And they made me an offer I could refuse, but I didn’t, and I have been pretty happy there, you know? Virginia’s a big part of my mother’s history; part of my family from my mother’s side comes from Clark County, Virginia. I thought I was ready to come back. I had spent the whole time in California writing about East Tennessee and western North Carolina, which are the places where I grew up. And I said, “Well, I’d better go back and look at it and write about it in a better way.” You know, when I got here it all just disappeared, and I started writing about California. So, wherever you’re not, that’s what you’re going to write about. That’s what I figure. My poems all come from what I see, what I look at, you know; they’re not manufactured by my brain. Although, once I start out with what I see, then I sort of add in other things. Anyhow, but if you were going to ask me, “How do you think of your poems,” that’s my answer, so don’t ask me that. (Laughter)

Graves: Well, I guess I have to scratch that one off my list! Your poems begin in the visual, with the image, and you have written a fair amount about painting and the visual arts — do you work with any other art forms besides writing?

Wright: Well, I’m very visual, except for not being able to paint. You know, I’ve always admired and been jealous of painters. But I can’t do it myself; I can’t paint. And I can’t sing. I could dance when I was younger. But I could also write a simple declarative English sentence and that’s sort of what led me to writing, and like a lot of us, or a lot of people, I had the urge to write when I was in college. And it turned out that my mother had dated William Faulkner’s brother at the University of Mississippi. And all she could talk about was “Faulkner, Faulkner.” So, I read all of Faulkner before I was out of high school, which was really a mistake, because I didn’t understand any of it, you know? But then I remembered enough so that I didn’t want to go back and do it again. Anyhow, I said, “Well maybe I can write,” and strangely enough my mother encouraged me to try to write. Which is not always the case, you know, because your parents are afraid that you’ll turn into a writer and then you won’t be able to support yourself, and them, later on. But, I couldn’t do narrative or prose. It was always just purple prose; it was never a story. When I realized you could do writing in another way, which I found out when I was in the army, then I started writing poems. And I was obsessed for 50 years with that.

Graves: I was thinking about the time that you spent in the army in Italy, and how that led to your discovery of poetry when you were in your twenties, and probably discovering fiction and photography and painting and all the arts that present themselves to us at this point in life. I wanted to ask about how, fairly early in your career, you published translations of the Italian poets Dino Campana and Eugenio Montale. How did translation inspire your own poetry? Do you think that the translations helped you discover anything about your own style or your own approach as a poet?

Wright: Well, I guess surely it did, though not Dino Campana so much. He was just a madman, but he was greatly loved in Italy, and I liked his work, too. But the one who really did influence me, or take me in, was Eugenio Montale. I got onto him when I was a Fulbright student in Italy, and after three years in the army I was able to go back (you know, still on the government’s dime). I was very fortunate, and I had a teacher over there who came down from Florence once a week to teach a class in Rome, where I was studying. She said, “Well, what do you guys wanna do?” and I said, “Why don’t we study Montale and Dante?” And she said, “Done!” Those are her two favorites, which I didn’t know at the time, but if I had, I’d still have said that. We translated some Dante and then I got very much into it. And the best way to understand a poet is to translate him, no doubt about that. I learned a lot from Montale about non-sequential images, jump cuts in the display of your poems. I guess that was very natural for him and became sort of natural for me after I discovered what was going on with it. Montale is kind of impossible to translate because he was very opaque. Beautiful, but opaque. And I said, “That’s what I wanna be: beautiful, but opaque.”

Graves: Sounds like poetry!

Wright: I wanted to be beautiful and clear, but you know, it didn’t work that way. So, that was what got me going, and I say that the best way to understand a foreign poet is to be able to translate him because you know what he’s doing — or she’s doing — and you can either appropriate it or at least put it in decent English. Italy changed my life. I was a country boy from East Tennessee. I was pure Kingsport when I went there, even though I’d been off to college and everything else. We had a lot of industry in Kingsport back in the day, but we didn’t have museums and that kind of culture, so I didn’t know what was going on in that world. You know, I got over there and saw all this beautiful country and all these wonderful paintings, all this stuff that grabbed me. The army was the best thing that ever happened to me. Fortunately, they weren’t shooting people in those days, so I was a Cold Warrior. I sat at a desk the whole time I was there, and I did take a lot of leave and go to these places in Italy that I’d been reading about. And the whole world opened up to me, you know? I mean, I could’ve gone to Surgoinsville, and it would’ve been the same thing, but it didn’t happen that way.

Graves: “Surgoinsville down the line,” as you say in “Appalachian Farewell.” I am glad that you mention Montale’s style because I want to discuss the style of a specific poem of yours. In “Appalachian Book of the Dead IV,” your speaker says, “This is the lesson for the day: narrative, narrative, narrative.” Yet, your poems haven’t dealt all that explicitly with narratives, or the stories within poems as so many Southern poets seem to do. I wonder if you can say something about your relationship to narrative and poetry and what you’ve looked for or as an alternative to the narrative?

Wright: I can’t do narrative. I can’t tell a story. I’m the only Southerner I know who can’t tell a story. Well, my father couldn’t tell one, either, so I’ve kept up the reputation. That’s why I couldn’t write prose, because I couldn’t tell a story. Then I discovered this poem when I was in Verona at Lake Garda. Outside Verona, this poem by a man named Ezra Pound, who I’d never really heard of before. And it was not narrative; it just talked about what he was looking at and what was behind what he was looking at. I was very taken by this, and I thought it just sounded so beautiful. Only later did I realize it was in iambic pentameter, which I didn’t yet know what iambic pentameter was. I found a lot of appeal in the idea of placing images on top of each other in stanzaic form, hoping that there would be some underlying narrative to them, which I think there is. That’s the way I side-stepped the story. The story had to unfold through the images. I wanted to be beautiful and opaque, and that’s how I was. I became an Imagistic poet, a guy who wrote Imagistic poems. I should say: “A poet is what someone else calls you,” as Robert Frost said. Never call yourself a poet. Let someone else do it.

Graves: So, the image took on a greater role than the story?

Wright: Lyricism holds a great fondness for me because I like the sound of the images, and I like the density of the images. I like to read narrative in other people’s poems. I can dig that. I just can’t do it myself. So, you always like in other people’s poems what you can’t do yourself, I’ve found.

Graves: You mentioned Ezra Pound and the Imagists, and I appreciate how you have paid tribute to poets and artists who have been important to you. One of my favorite examples of this is “In Praise of Thomas Hardy” in one of the later books. I wonder if you can talk about how those influences have evolved over time? Did they change as you grew and matured as a poet?

Wright: Yes, I guess how I have used my influences has changed. Basically, I stopped stealing from my favorites and sort of managed to put it all into my own way of doing things. Everybody steals something from other writers — I mean, that’s the nature of the beast — because writing doesn’t get better or worse; it just gets different, and you keep changing what has been done into your own way of doing it. It’s true, I do have a lot of homages to other poets. Basically, other poets that I lifted stuff from, you know, and tried to launder without leaving the country. Anything you like, you store it, and you want to appropriate it for yourself if you can. If it is in your field of vision, then that’s what you do. There have been a lot of painters that I have taken things from, like the poem “Homage to Paul Cezanne.” I wrote that poem, I thought, trying to imitate the way he painted. I was trying to imitate in words what he was doing with paint and brush strokes. I didn’t succeed, of course, but that’s because it’s a painting and mine was words, but I think it helped me write that poem. There are other examples, like Mark Rothko and Claude Lorrain. I did a Rothko homage, which I wrote in three groups, the way his paintings are: small, small, and large in the middle.

Graves: The poems about painters are some of my favorite poems of yours. You often use song lyrics or titles from popular songs and especially from folk ballads, like “Hello Stranger” or popular songs like “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted.” These are cultural touchstones for us as writers and reference points for readers. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about how those came to play such an important role in your poetry?

Wright: Well, first off, the titles usually had nothing to do with the poems. I just put the title in so I could have the phrase up there. That’s not always true, but it often is. I became a great fan of titles. And as my inspiration waned from poems, it grew for titles, you know? Most of them are from country songs that I heard growing up which I still like. So, I would just recall something like, “Get up, rounder, let a working man lay down.” I think that’s a great title, but it doesn’t have anything to do with the poem as far as I can remember. It’s not a good thing to do titles that don’t have anything to do with the poems, and I don’t recommend it to any younger writers. But it seems to have worked for me. (Laughs)

Graves: One kind of lyric transfers to another, and the songs become parts of the poems. I find this very natural to bring different types of lyrics together.

Wright: I did have something called “Titleism” that I invented many years ago. I worked it out with my friend Charles Simic, and it had to do with what a title can do for a poem, and what it can’t do. The idea was sort of based on Frank O’Hara’s “Personism,” which doesn’t have anything to do with anything and neither does titleism have anything to do with anything. It’s just fun to do. I have always been a great hoarder of titles. I’ve never been able to just call something “Poem” and leave it at that.

Graves: I would probably read a book made up of just Charles Wright titles. I’m glad you brought up “Titleism” because I thought that was such a smart and funny thing to do, and it shows a different aspect of your work. Your poems are not usually known for their humor — you are known as a writer of serious poems. I think at one point you said you wrote about “The Metaphysics of the Quotidian,” of the everyday world in the backyard. You mentioned that you wouldn’t advise young writers to write titles that don’t have anything to do with the poems. So, naturally, the next question is: What other advice do you have for young writers?

Wright: I have no advice to give to young poets. You gotta figure it out yourself. (Audience laughs) I really don’t, you know? It’s terrible to give advice to people. That’s why I was never a very good teacher. I didn’t want to tell them what to do. There are certain people you take aside and say, “Listen, you can do this, so keep on at it, no matter what happens.” But I don’t have any advice, except stay away from all advice, you know, because it’s usually going to be wrong for you and right for the person who’s giving it. William Stafford used to have a suggestion for people who said, “This poem isn’t going anywhere. What should I do?” and he said, “Lower your standards and keep on going.” Which is not a bad thing to do because you can get your standards back up once you get over that hump.

Graves: Well, that’s great advice. I had a feeling you might say, “Someone once told me the first vice is ad-vice” and leave it at that. But it’s hard when you’re a writing teacher, isn’t it? You are supposed to offer direction, but really what you want to say is, “You are your own writer and you have to find your way and to keep looking until you find it.” So, you are part of a dynamic generation of American poets and international poets. Without putting you too much on the spot, I hope, I wonder which of your contemporaries, or maybe poets just a little before you, that you’ve learned the most from and that you’ve read with the greatest interest through the years?

Wright: Of my contemporaries, the ones I read most are Mark Strand, Charles Simic, James Tate, C.K. Williams, David Young, and Louise Glück. In the group ahead of me, I admired Philip Levine, and I learned a lot from Donald Justice, who was my teacher when I was at the University of Iowa, which is another story, indeed, let me tell you.

Graves: I would definitely like to hear that one.

Wright: I got into the University of Iowa because I was just getting out of the army and I got an early release because I had been accepted at the Columbia School of Journalism, which I didn’t want to go to. And then I submitted what I thought were poems to the University of Iowa in August, but remember I didn’t know what the deal was — I just wanted to write poetry and not go to journalism school. I think I got accepted into the graduate school at Iowa because I had a B-average from Davidson College, which is pretty good. I just showed up at the workshop, which in 1961 was not quite as organized as it is now. I came to class, made a fool of myself the first week and said, “I’m not going to say another word,” and I didn’t for two years. I just sat there and kept my ears open.

Graves: I think more writers probably wish they had done that in graduate school. I wonder if being a good listener isn’t one of our lost arts. But you must have written some good poems at Iowa?

Wright: Finally, I got to the point where I had written one sort-of-decent poem. I said to Don Justice, “How in the hell did I ever get in here? I mean, I know that was crap that I had sent.” And he said, “Oh, I don’t know, better ask Paul Engle, I wasn’t here then.” And I asked Paul, and he said, “I don’t know, ask Don Justice, I was out of the country.” So, I was never let in by one of the professors, I just walked in the door and started taking classes. And here we are — the rest is history.

[Find more about Charles Wright at Chapter 16, including Bobby C. Rogers’ 2016 essay from the Pulitzer100 project, here.]

Jesse Graves is the author of four poetry collections, including Merciful Days, and a collection of essays, Said-Songs: Essays on Poetry and Place, among other works. His work received the James Still Award for Writing about the Appalachian South from the Fellowship of Southern Writers and two Weatherford Awards.